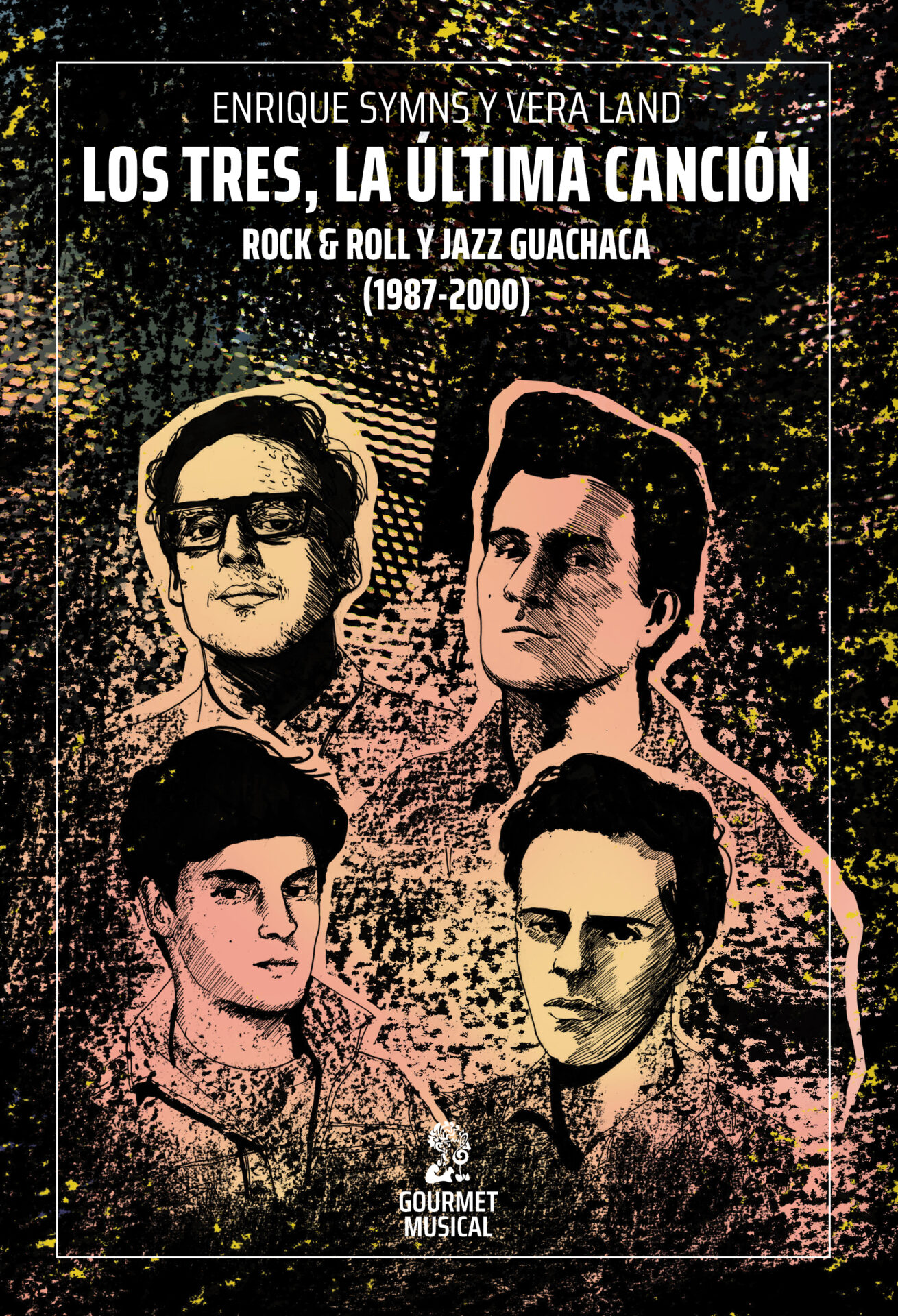

When Los Tres, la última canción came off the presses in February 2002, I was back in Argentina. The controversy unleashed close to the end of the research phase and deepened during the editing process dampened the release.

During the time of the book’s undertaking, I saw the bullets fly, after a point of no return when the differences between Enrique Symns and the band became irreconcilable. Although it seemed to me that Álvaro Henríquez had his own considerable reasons, I remained loyal to Symns because he was the person who had chosen me as coauthor. To choose or to be chosen. Is that a determining factor?

Some of the chapters in the book had taken an uncomfortable turn for Los Tres and didn’t represent the story they wanted to tell. That’s why they decided to deauthorize the biography, which was a good choice in terms of getting past the conflict. But it put me in a foul mood because the controversy obscured the work we had done, which was rigorous and devoted.

Before the fallout, in the golden months, I enjoyed the research. I interviewed musicians, actresses, singers, theater and film directors, cultural journalists, owners of rock bars, music producers, artistic producers, sound engineers, poets, writers, family members, ex-girlfriends, friends. I really had a good time, all interesting people from the other side of the Andes rooted in artistic worlds that seemed to me parallel to the ones I had formed a part of in Buenos Aires. Despite the isolation resulting from the dictatorships, we had a lot in common, and the generational understanding flowed. I connected perfectly with the artistic environment that surrounded Los Tres and I tried to reconstruct part of the Penquista underworld of the eighties. I was enveloped in a perfume of adventure. I wasn’t familiar with the music of Los Tres beforehand and I was fortunate to have liked the lyrics, the melodies, the instrumentation, and the sound. I read newspaper and magazine clippings that furnished me with information about the beginnings of the band and I milked the album booklets for all the data they were worth. I was fascinated by Álvaro Henríquez’s intelligence and sensibility and the entire ambitious project of creating Chilean rock. They weren’t the only ones, because the Electrodomésticos, Los Prisioneros, Colombiana Parra, and others, male and female, also went on a search for identities, but they were the most far-reaching due to their revindication of cueca music and their reaching into the recesses of what it means to be Chilean with Roberto and Lalo Parra, creators of guachaca jazz.

The announcement of the breakup had placed the band in the central focus of dramatic expectation for its followers, and of a lot of coverage in the press. Álvaro, Titae, and Pancho had been together since they were fourteen years old. They needed new tunes, to walk down other paths, have other experiences. Were they separating just to have some breathing room? Was Álvaro’s leadership in question? Was it a way of capturing, once again, the attention of cultural society? Typical conjectures surrounding the problems of rock bands over time. Of all their reasons for separating, Ángel Parra was not one of them. For him, the band was good enough the way it had been functioning. The nucleus of the crisis occurred among its founders.

Translated by Luis Guzmán Valerio