As a career diplomat, Octavio Paz was posted twice to India. The first sojourn was for a brief period of six months, from December 1951, as the Second Secretary to assist in setting up of the first Latin American embassy in the newly independent India. The second time was a decade later in 1962, when he lived in New Delhi for six years as Mexico’s ambassador. That period was so momentous in terms of his creative and emotional life that he called it his “second birth.” Paz’s arrival in 1951 and departure in 1968 were both consequences of diplomatic scandals that resonate to this day. The earlier instance was a case of punishment-posting for mobilising French cultural opinion against his own government’s banning of Luis Buñuel’s film Los Olvidados (1950), when his actions compelled a reversal of the ban. Likewise, Paz’s departure was the result of his resignation against his own government’s massacre of student protestors at the Plaza de Tlatelolco on October 2, 1968. Both instances underline Paz’s liberal, activist facet, and his life-long battle against all forms of authoritarianism. Instead, his nuanced political positions have been consistently misunderstood, especially till his death in 1998, as indicative of right-wing sympathies.

During Paz’s first stay in India, he hardly made any friends, lived largely within the confines of his hotel, and did not like either New Delhi or the people he met. Later, he reassessed his own responses as partly a projection of his own unhappiness and partly the impact of deep-rooted Western prejudices he unconsciously carried within himself. The first trip thus prepared him mentally for the longer stint of six years, which he often called the happiest years of his life.

The second stay (1962-1968) marked the most creative and productive years of his entire life. He fully immersed himself in India’s history, philosophy, art, and literature. His house became a meeting point for Indian artists, writers, and thinkers, and much of his poetry and essays emerged out of that joyfulness: Ladera este, Hacia el comienzo, Blanco, El mono gramático, Corriente alterna, Conjunciones y disjunciones. He also found the great love of his life during that period, Marie-José Tramini—an inseparable part of his subsequent poetry.

Never in history has a major Latin American writer been so deeply engaged in an intercultural dialogue with the Orient. While in India, Paz did not write only about Indian themes. He wrote a book of anthropology, Claude Lévi-Strauss o el nuevo festín de Esopo (1967), and one of the two long essays on painter Marcel Duchamp that became Aparencia desnuda (1973). He also wrote extensively on world politics and world literature, contributed to various anthologies, and revised earlier editions of his own works. While in India, Paz wrote copious notes for a book that would later develop into La llama doble (“the double flame”), published in 1993, where he contrasted ideas of love in the Western and Indian traditions, often tracing them to the difference in their musical structures.

Paz was well aware that he belonged to a long Latin American tradition of writer-diplomats: Gabriela Mistral and Pablo Neruda, Miguel Ángel Asturias, Rubén Darío and Alejo Carpentier. Since the nineteenth century, some of the most distinguished Latin American writers, though not career diplomats, entered politics and became presidents, such as Rómulo Gallegos of Venezuela, and Domingo Faustino Sarmiento and Bartolomé Mitre of Argentina. José Martí died in 1895 fighting for Cuba’s independence from Spain. Neruda was nominated for the presidency; Vicente Huidobro actually ran for the presidency, albeit unsuccessfully, as did Mario Vargas Llosa. In Mexico alone, the list of writer-diplomats includes distinguished names such as Carlos Fuentes, Alfonso Reyes, José Juan Tablada, Federico Gamboa, José Gorostiza, Jaime Torres Bodet, and Maples Arce, all of whom were colleagues of Octavio Paz. As a public intellectual, the Latin American writer’s political position is one of vital public interest, more than anywhere else in the world.

Paz’s life stands as a shining example of how the advantages of diplomatic life can be used for maximising literary output. His Paris years fired up his mind by bringing him into close contact with the European avant-garde; his years in the US shaped his poetry through a close contact with Anglo-American literary sensibilities. Paris was also the rallying point for Latin American writers and artists to discover their continental commonalities. Living at a distance gave them a different perspective from that of the regular insider. The close experience of faraway cultures such as India gave the cosmopolitan Paz a non-Western vision of life. He spent a significant part of his time travelling by road across the Indian subcontinent. Paz hosted Julio Cortázar, Severo Sarduy, and Rufino Tamayo at his home, and they experienced India through him. While in Delhi, he also forged deep friendships and collaborations with American composer John Cage, dancer Merce Cunningham, and painter Robert Rauschenberg, as well as creative relationships with a wide array of Indian painters, writers, and intellectuals who shaped “modern” Indian culture.

As part of diplomatic protocol, Paz had to submit his credentials to India’s prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, five days after arriving in India. He was amazed by Nehru’s elegance and sophistication, which managed to shine through in his last years despite the long years of struggle and India’s humiliating defeat in the Sino-Indian War. He had the opportunity to know Nehru “from closer range” when he visited an art exhibition of young Indian artists that he had organised. Paz keenly read his books and listened to his speeches. He was inspired by Nehru’s ability to combine flexibility with energy and intellectual finesse with political realism.

A few days after meeting Nehru, Paz presented his credentials to the president, Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, a philosopher-politician in the Platonic tradition. Paz noted that “when philosophy is put into action, it becomes pedagogy, which, in its highest form, is politics.” He referred to Dr. Radhakrishnan’s scholarly work, mentioning that there was nothing more satisfying than greeting a Head-of-State who was also a maestro and pursuer of truth.

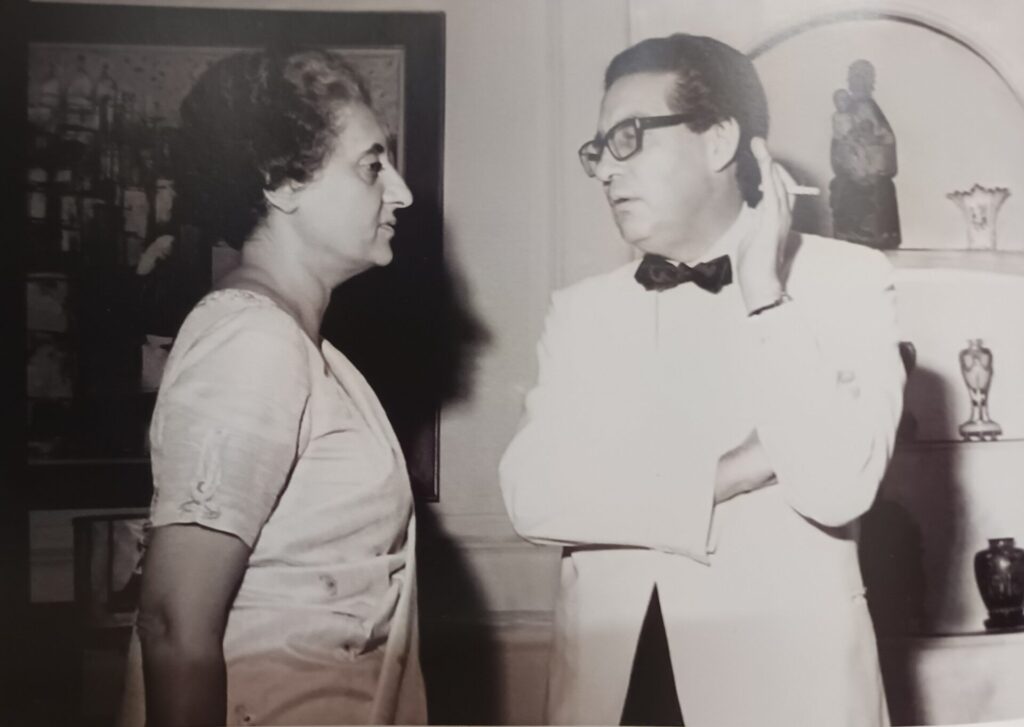

Paz had met Indira Gandhi along with her father (Nehru), but after his death in 1964, she became a cabinet minister. It was then that Paz met “Señora Gandhi” quite frequently and they became close, well beyond diplomatic protocol. Since India did not have any specific policy for Latin America, she relied on Paz for drafting a policy for the region. She had travelled to Mexico in 1961 and thus knew of its similarities with India but was relatively lost when it came to the other Latin American countries. Paz sheds interesting light on her by contrasting Indira with Nehru:

Nehru was an intellectual with a political vocation, Indira Gandhi was essentially a political being. Nehru got lost at times in generalities and grandiose-but-vague schemes. Indira was concrete and sober. […] She sought the friendship of writers, poets, and artists, and I was always surprised by her intelligent involvement in ancient as well as contemporary art. (Nehru Memorial Lecture, 1985)

Paz thus conveyed his assessment of Indira Gandhi as a master of realpolitik.

When Paz left India abruptly after his resignation, Indira Gandhi organised a party at her residence. Later, she met Paz during her official visit to Mexico in 1981 and invited him to deliver the annual Nehru Memorial Lecture in 1984. Since he was also invited by the Japan Foundation that year, Paz decided to combine the two trips. He was in Kyoto, ready to depart for New Delhi, when he heard of Indira Gandhi’s assassination on October 31. In his hotel room, he watched on TV the horror of the mindless anti-Sikh riots and massacres that followed her death.

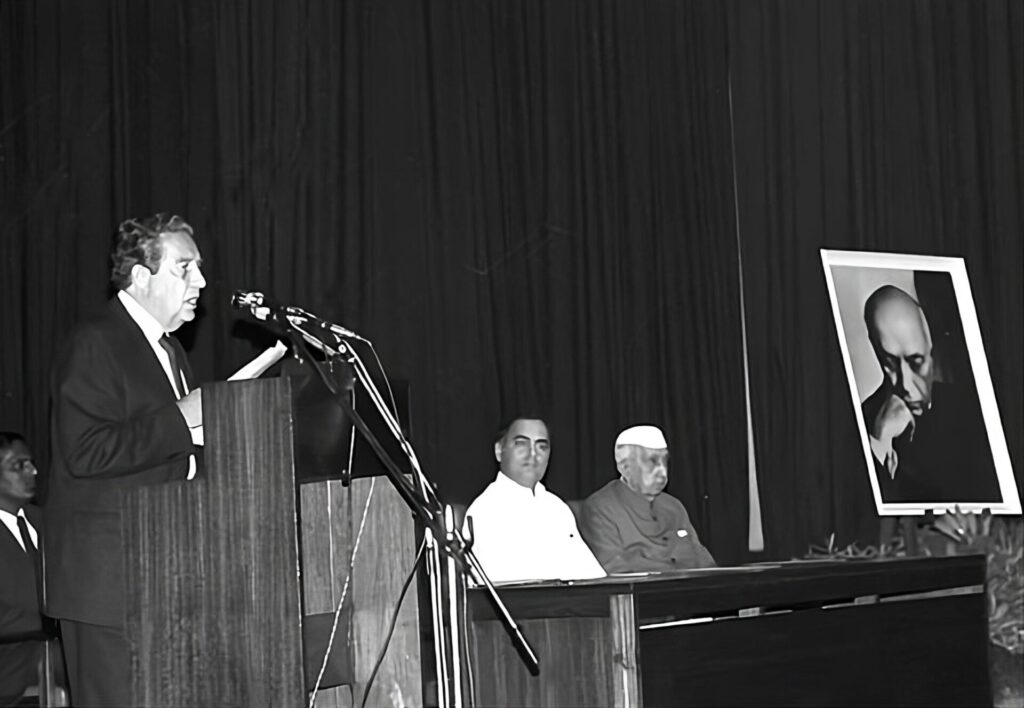

The invitation for the Nehru Memorial Lecture titled “India and Latin America: A Dialogue Between Cultures” was extended to Paz in 1985 by Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. The text of that lecture formed the core of his memoir of India written in 1995, three years before his death: Vislumbres de la India (In Light of India, 1997). It suggests the humility of his personal vision in the face of “the immense reality of India”:

…[M]y education in India lasted for years and was not confined to books. Although it is far from complete and will remain forever rudimentary, it has marked me deeply. It has been a sentimental, artistic, and spiritual education. Its influence can be seen in my poems, my prose writings, and in my life itself. (23)

Political Interventions

The declassified diplomatic archives of Octavio Paz reveal several little-known facts of public history. He played an important role in the “Liberation of Goa,” which started in 1961 and was formalised in 1962. The Portuguese considered it an “annexation” by Indian Armed Forces, which put an end to the 451-year-long Portuguese overseas colonies. By the time Octavio Paz arrived in India, the Mexican embassy was already involved in the Portugal-Goa conflict, proposing to use its position in Latin America to establish a dialogue with the Portuguese authorities in both Goa and Lisbon. Nehru suggested that Paz mediate with Portugal. Ironically, the Portuguese embassy too requested that Paz mediate their case with India, as they preferred a third party through “the long and complicated process.”

Though Paz was firmly in favour of Goa’s integration with India, he sought a delicate diplomatic balance in his negotiations with both the governments, emphasising that it would be a terrible mistake “if Goa’s Latin cultural values” and ambience were negated in the name of decolonisation. He made this point emphatically and repeatedly to high-level Indian government officials whom he met. Some of them disagreed with him and argued for the “Indianisation of Goa.”

Paz’s regular diplomatic dispatches to his government about developments in South Asia were meticulously drafted and elaborate. His concerns about the causes behind the Indian student rebellions since 1966 and the Indian government’s way of dealing with them foreshadowed his eventual exit around the student rebellion in his own country.

Political concerns apart, Paz undertook several cultural initiatives that were innovative and unprecedented, carried out with zealous enthusiasm. He tried to disseminate awareness of Mexican culture in India by organising a large-scale travelling exhibition of Mexican handicrafts in India in 1965 and vice versa, drawing attention to their similarities. Titled Portrait of Mexico, the highly successful itinerant exhibition started from Manila and moved eastwards to Calcutta, Madras, and New Delhi, ending in Bombay.

Octavio Paz also played a key role in the first-ever exhibition of tantric art in Europe, contributing to its catalogue in 1955. In February 1970, the first landmark exhibition of tantric art was held at Le Point Cardinal in Paris, followed by exhibitions in Milan and Rome. At that time, many Western writers and artists became interested in tantric art under the influence of the Theosophical Society.

Paz also undertook some pioneering commercial initiatives. In 1964, he executed a trade deal for the large-scale Indian export of cinnamon to Mexico. Though cinnamon had been used earlier in Mexican cuisine, its use became increasingly popular, particularly in sweet dishes, salads, baked products, mulled wines, and other drinks. Mexico gradually became the world’s second largest consumer of cinnamon. Though his diplomatic work was not very demanding, he maintained a basic work ethic, keeping his writing life separate from his diplomatic work. He never did any writing during office hours apart from official reports and letters.

Paz’s earnest concerns for the food and hunger situation in India prompted him to extend a helping hand. He spoke to Señora Gandhi about high-yielding wheat seeds that were developed in Mexico, leading to their Green Revolution in the 1950s. With her encouragement, he imported large quantities of short-strawed, high-yield, disease-resistant wheat varieties developed in the state of Sonora that had given outstanding results and came to be known as “Sonora seeds.” Paz even enabled the transfer of know-how by sending Mexican officials to work with farmers in the fields of Punjab. Despite his pioneering initiatives, the entire narrative of the success of the Green Revolution was usurped by the Rockefeller Foundation and the American agronomist, Norman Borlaug. Diplomatic exchanges show that Octavio Paz tried repeatedly to correct the narrative by demanding credit for Mexican scientists who were eclipsed by the Rockefeller Foundation.

Resignation

The story of Paz’s dramatic resignation in October 1968 may look a bit more nuanced when we take a closer look at the archival documents. He was planning to resign from the diplomatic services anyway and return to Mexico to start a journal. Political developments only brought it forward and, paradoxically, delayed his return to Mexico by two years due to the hostility of his own government. Octavio Paz carefully drafted his resignation letter in officialese to make it sound not like a resignation, though it was written in “pain and anger.” He had a personal stake in being deprived of his well deserved pension after twenty-three years of diplomatic service.

He characterised his moment of departure as “bittersweet” because of the overwhelmingly warm responses he received in India in favour of his decision. An endless stream of strangers visited his bungalow to congratulate him. When he reached the train station to catch a train to Bombay (where he would board his ship to Europe), he found a crowd had gathered to bid him farewell. Students, writers, and artists waited at railway platforms in all the intermediary train stations with garlands in their hands till late hours of the night, to convey their respect for him.

Paz never regretted his decision and never yearned for a return to diplomatic services. He was grateful that it provided him the opportunity to travel to faraway countries and cities and meet people of diverse languages, races, and human conditions. Above everything else, he felt grateful because it gave him India and Marie-José, who became the centre of his life and poetry.

Author’s Note: This brief essay is a very reduced version of a longer (12,000-word) essay on the same topic, which forms part of the book The Tree Within: Octavio Paz and India, which is slated to be published by Penguin in 2025.