One of the central topics of the Colombian literature of the last two decades has been how to build narratives and structures that allow for the recovery of personal and national memory surrounding the traumas left by the conflict. Since the signing of the peace treaty with the guerrilla group, the FARC, in 2016, the thematic interest of the literature dealing with the conflict seems to have shifted from the immediate recounting of the horrors of war to the question regarding the manner in which the roads toward the restoration of memory are being created; a step that would follow the apparent ending of the armed conflict. Even though the conflict is still ongoing (albeit with different dynamics and social dimensions), when memory became a thematic axis in art, it raised a question that still drives many current narrative agendas: how can a memory of the conflict be constructed?

The need to narrate a conflict in the immediate present (which led to the overuse of literary forms that leaned toward the testimony, the chronicle, and journalism) transferred into the search of a grammar that could equate to the confusing manner in which victims reconstruct memory (which does not correspond to the linearity of History). Thus, the focus moved from the event to the exploration of form, both unavoidably intertwined. Some literary works that were still attached to the reified realism of History opted for autofiction and linearity. Meanwhile, others chose peripheral structures and genres that allowed for more symbolic or metaphoric representations, creating a new way of addressing the conflict. Among the latter proposals, graphic novels are one of the most prolific, yet surprisingly least studied, genres. Some examples of graphic novels that stand out are La peste de la memoria (2016) by Juan Pablo Salazar and Ramiro Ramírez, Labio de liebre (2020) by Fabio Rubiano with illustrations by Pipex, and Liborina (2020), which is a novel drawn and scripted by Luis Echavarría Uribe that epitomizes these highly diverse narrative proposals.

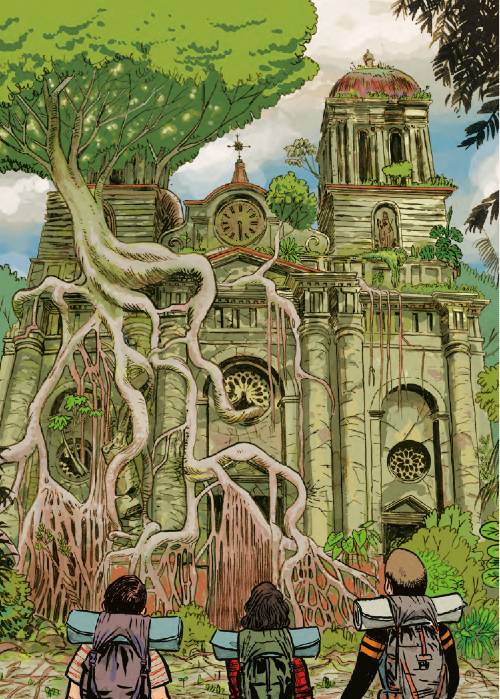

Liborina begins with an alternate history premise: Colombia’s National Soccer Team has won the 1990 World Cup, which brings about the end of the armed conflict and triggers a transformation of the nation’s self-perception. The storyline, nonetheless, is not set in the present of that alternate history, but in the future, in the mid-2040s. We follow three young people who have decided to enter a protected area (which covers a territory larger than that of the department of Antioquia), where entry is forbidden. They are after a story that has become almost mythical: the natural park was created by the State to cover up everything that happened during the years of the conflict; there is talk about a relocation of the people who used to live in the area, but the real events are yet to be known. Martín, Raúl, and Juliana, upon finding the ruins of a supposedly evacuated town, come face to face with a violence that emerges as a hauntological redoubt of what the conflict signified.

There are several elements that stand out in this graphic novel. The first one is the alternative history genre, uncommon in Colombian literature. In other Latin American countries, alt-hist novels have served as fantasy spaces in which to sublimate a specific historical desire that has not been fulfilled. In Colombia, however, these novels have not been produced on a recurrent basis. With the exception of works that set their storylines outside the country, in Colombia only a few stories of this genre can be found. All of them have their Jonbar hinge in the Bogotazo. An alt-hist story set at the end of the century allows for the creation of a temporality that breaks ties with history in order to highlight that which has always been veiled by The Real. The author’s decision is to radically distance himself from the historical structure by deconstructing this temporality. Hereby, he chooses not to represent from the referent, but from the rarefaction or estrangement of the truth. This is how the past, present, and future of the universe created by Echavarría appear as imaginary constructions. The geographical (and linguistic) markers, nevertheless, continue to point to Colombia (the characters have a highly discernable Antioquean accent, for example). The perception of the national, thus, is transferred to two spaces: on the one hand, to empty symbolic referents, and, on the other, to a historical event that exists, mainly, in its concealment: the armed conflict.

With this turnabout, Echavarría seems to point to the fact that, aside from the construction of memory, there is a latent need to highlight the violence of the obliteration that is being imposed upon us by state institutions. It is, therefore, imperative to denounce not only the erasure of the individual and collective memory, but also the implementation of a narrative that completely effaces the conflict. The character of Juliana initially thinks: “this here is just scrubland (…) the rest is sheer myth,” and national history pre-1990 has long been forgotten; it has long merged with the landscape. Nonetheless, the protagonists eventually find out that, underground, like a subterfuge of language, lie the victims who only have violence and state oblivion left as community structures and narrative forms. The novel quickly takes on the structure of a slasher in which the sediments of a conflict that constantly resurfaces as a symptom can be easily discerned.

All of this is closely connected to the emergence of graphic novels as narrative devices with which to portray the conflict, hinting at what Graham Harman, in his book Weird Realism, refers to as a “rift.” In this rift, real objects are trapped in a linguistic impossibility that results in a paralysis of meaning and obstructs the formation of a direct relationship between that which is seen (the observable object) and the different forms of historical representation. From that standpoint, the spot that greatly condenses the narration of terror in the Colombian conflict becomes most problematic in its impossibility of being narrated. This particularity had already been used in Colombian literature by authors such as Evelio Rosero, who replaced the forms of realism with those of surrealism in En El Lejero and madness in The Armies. Interestingly, this reflection on language seems to have reached its limits in Rosero’s works, which is why the quest for representation is redirected toward a change in format. This is how the graphic novel makes it possible to depict (no longer “narrate”) violence by means of graphic tools. In Liborina, the descent into repressed history entails pages with black vignettes and inverted color images. Likewise, the jungle (the space that the State is supposed to watch over) is transformed into a landscape of horror filled with cryptic and baroque textures, while the characters appear almost imperceptible in the midst of an unfathomable wilderness. These images intersperse with full-page vignettes of explicit violence that mingle with the orange tones of a primitive tribal feast.

Hence, the nameless takes shape in a book where the terrors of war and grammatical constructions no longer need to be named because now they are shown. The symbolic power of images has mutated with their evolution: instead of being mere reflections of The Real (as in news and chronicles), they have become meditated interpretations; they are now artistic constructions. At the same time, they are shown as something that both happened and did not, and it is in this back-and-forth between the historical and the fictional that the power of historical reconstruction through art emerges. Conflict, memory, and history are not, thus, mere materials for the elaboration of art. Rather, art is what bears the responsibility of establishing the proper structures so that history can flow through them. The image comes to the aid of a word that suffers from the vertigo of having an abyss between itself and its meaning. The image represents a horror and a fragmented memory that, in the terror of not being able to name, has become the main pillar of the reconstruction of a memory more plastic than it is linguistic.

Lastly, it is necessary to highlight how in Liborina the author draws from the structures of the so-called popular genres to narrate the conflict. Following Fredric Jameson’s idea, developed among others by Mark Fisher, nowadays the grammar of reality is an elaboration of capital. This vision is characterized by a relationship between reality and representation in which there is a simulation of absolute correlation. The way out of this structure is through the genres that Jameson calls magical and that Fisher notes are closer to the weird. In Liborina, the author uses precisely this space of epistemic uncertainty—which oscillates between horror (in its slasher variant), the alternative history genre, and the mythical—to introduce the most important aspects of the historical. This does not lead him toward providing a solution to the problem of memory. Rather, it helps him establish the grammar of memory in a place that does not intend to create a relationship with The Real, but rather points out the places in which the gesture, the symptom, and the lapse of memory can be found, as these are the places where the construction of the memory of the conflict lies. Contrary to the documental zeal of historical commissions, art finds potential narratives in alternate realities, structures, and, above all, non-mimetic genres. It is specifically from the peripheral (the place where these other-stories are told) that a grammar of the conflict and memory can be imagined: a narrative operation that is able to disengage from the reifications of The Real, and is capable of disclosing the traps of a historical narrative that has been appropriated by the State to disfigure the very concept of memory.

In a graphic novel such as Liborina, there are aspects that stand out in the process toward the possible construction of a contemporary narrative of the conflict: the deconfiguration of historical narratives, the construction of a gap of meaning that is rooted in other formats, and the pursuit of a grammar of memory. While the graphic novel is presented as one of the most interesting formats from which to reflect upon how to establish a relationship between history, reality, and art, Colombian literature is going through a period of change where possibilities for the creation of a different proposal are opening up. These types of works allow us to ponder how to move from a testimonial literature to one that reassembles the structures of memory and, nowadays, points out the ways in which History and conflict are erased by the State. Finding these gestures in disruptive formats, such as the graphic novel, facilitates the understanding of the new dynamics in which conflict and violence continue to be inescapable themes in Colombian literature.

Translated by Ana Gabriela Pérez

All images from Liborina by Luis Echavarría Uribe, Planeta Cómic, Bogotá, 2020