Editor’s Note:

Bogotá39 is a project by the Hay Festival and Bogotá: UNESCO World Book Capital City to name 39 of the most promising Latin American writers under the age of 39. The first list was assembled in 2007, and a new list appeared in 2017. Beginning in the current issue, Latin American Literature Today will feature works by the young authors selected for this prestigious recognition. View the full 2017 list here.

Here, we present 39 books by the 39 authors included in the 2017 edition of Bogotá39:

Carlos Manuel Álvarez: La tarde de los sucesos definitivos

Carlos Manuel Álvarez debuted with a collection of seven short stories that, taken together, form the emotional geography of Havana, where its characters cross paths in the narrow streets, on the Malecón or in the beca (a student dormitory). Far from enchanting, this is a brutal look at migrations, broken relationships, and slippery slopes. Even though the Chilean author Enrique Lihn and the Cuban poet Ángel Escobar—who apparently has not committed suicide, but rather chosen to open a bookstore in some parallel, invisible world—make appearances, this book manages not to step in the footprints of previous generations. Rather, it walks its own path: that of contemporary Cuba and the children of the nineties. La tarde de los sucesos definitivos does not hesitate to be experimental, but at the same time it does not fear to propose a prose based in realism and pushed forward naturally in a way that only one who trusts in his own talent can accomplish.

Frank Báez: Postales

In Postales, Frank Báez, winner of the 2009 Premio Nacional de Poesía Salomé Ureña, passes through cities, emotion, and diverse poetic registers in a sort of metaphysical journey that traces a map not only of his soul, but also of the contemporary world. From Santo Domingo, where he weighs anchor, to Chicago, where he is buried in snow, Báez send us his postcards in the form of poems. Postales captivates us; it makes us laugh, reflect and cry.

Natalia Borges Polesso: Amora

It would be unfair to state that the stories found in Amora are merely about homosexual relationships between women. Marvel, surprise and fear are also found in the text. We find ourselves beside ourselves, above all when the book departs from the bounds of normalcy and is allowed to explore challenges and to change the impossible, continuing with its transformative process. It is necessary to advance and explore the unknown, destabilizing all structures so that one can ultimately arrive at the calm of honest living.

Giuseppe Caputo: Un mundo huérfano

In a neglected neighbourhood with patchy services and barely any electricity, populated by endearing, larger than life characters, a father and son struggle day by day to stay afloat. Rather than being discouraged by their difficulties and hardship, they are spurred to come up with increasingly outlandish plans for their survival. Even when a terrible, macabre event rocks the neighbourhood and the inhabitants start to flee, they decide to hold out. At the end of the day, the most important thing is for them to stay together.

Juan Cárdenas: Zumbido

After receiving news of his sister’s death, a man begins an escape that carries him to the congested center of a Latin American city. He reaches its suburbs, which are locked in a battle for dominance with the jungle. Everything in this man’s journey becomes part of a larger drift. He lives, together with the friends he makes along the way, as if in the stunned reality of the survivors of a catastrophe. This lends itself to the perpetuation of the escape: continuing, advancing, moving forward… the life of a modern man.

Mauro Javier Cárdenas: The Revolutionaries Try Again

Extravagant, absurd, and self-aware, The Revolutionaries Try Again plays out against the lost decade of Ecuador’s austerity and the stymied idealism of three childhood friends—an expat, a bureaucrat, and a playwright—who are as sure about the evils of dictatorship as they are unsure of everything else, including each other.

María José Caro: La primaria

Macarena has to the confront her parents’ separation in the middle of the school year. Each story more closely develops a moment in the life of this girl as she considers her place in the complex world of primary school. Over the course of the six stories, it becomes evident that Macarena must accept the separation of her parents and the new engagement that one of them undertakes. She must meet the humiliation that she suffers when she believes that she has finally been accepted by the most popular girls at school and the insecurity that she feels upon being separated from her junior basketball team. She must face the embarrassment that falls upon her when she learns that she cannot dance. These stories show that the earliest years of life are not always as fun as they seem.

Martín Felipe Castagnet: Los cuerpos del verano

Los cuerpos del verano belongs to the family of great works of imaginative science fiction. A world where the dead have the option of returning to a body thanks to advances in medicine and the Internet allows for the configuration of a third possibility for existence. The author thus constructs a new universe—a simultaneously melancholy yet hilarious obituary about our relationship with the web and its common problems. This learned work has fascinated readers, critics, and booksellers, and has already been published in French, English and Hebrew.

Liliana Colanzi: Vacaciones permanentes

With a simple narrative style, hypnotic yet dizzying, Liliana Colanzi speaks to us from the edges of the adult world and the end of an era; from isolation and the search for personal salvation that ends with the commission of the same mistakes as those of parents and family. It becomes progressively more difficult to maintain distance between a good story and how a good story ought to be. One of the most certain, wise possibilities of resolving that mystery comes in the form of Liliana Colanzi’s fiction. These are stories overflowing with light and shadows and, above all, perturbing chiaroscuros. They are written with a rare astuteness and an enviable maturity that are like a visit to a new, faraway planet that feels familiar and close.

Juan Esteban Constaín: El hombre que no fue jueves

Shortly before stepping down, Benedict XVI shakes the dust off an old process in order to canonize G.K. Chesterton. The cause is supported by a strange occurrence that took place in 1929, when the great English writer did a service for the Church at the request of Pious XI, and over which a heavy veil of silence was draped. The documentation, jealously guarded for years, comes to light once again during the rivalries, robberies of documents, and scandals that plagued the Church at the beginning of the century. The effort is based in a good cause, but there are many mysteries contained in those old pages, along with many enemies. This novel—fun, delirious and profoundly serious – is as much an homage to the eternal creator of Father Brown as it is a demonstration of history, with its political, religious, and even literary intrigues.

Lola Copacabana: Buena leche – Diarios de una joven (no tan) formal

This is the intimate diary of a twenty-five-year-old Argentine girl from a very good family. Lola Copacabana describes the obsessions of a girl as unique as she is similar to others. We encounter sex, maternity, waxing, men, law school, parents and friends. With humor, ease, and great style, Lola describes urban places and people. Written between her twenty-second and twenty-fifth years, in accordance with the long tradition of girls’ diaries, the reader will become an intimate witness to the vicissitudes of growing up, the end of a great love affair, vocational uncertainty, and the first move out of mom and dad’s house. Full of unabashed praise of feminism, these notes by Lola Copacabana came from a blog in which readers from all over the world greet those who are in love or indignant, delighted or reluctant, but always attracted by adventures, shipwrecks, and the victories of an enchanting daily routine. Irreverence, sarcasm and buena leche cover these pages, evoking voyeurism and tenderness.

Gonzalo Eltesch: Colección particular

The neutral manner in which Gonzalo Eltesch has built this story is not without ferocity. The narrator is constantly revising, reconstituting the facts of life already lived in order to show, in a way that does not alter the diminished tone of his words, painful and uncomfortable truths. This is both the story of a family and the story of a solitary man, told with a strange vibrato of retrospective objectivity.

Diego Erlan: La disolución

This is the story of Simón and Monserrat – or the splinters of that story, because it is not a story of love, but of rupture. After the vertigo of a disproportionate relationship, Simón is immersed in the chaos of memory: he accumulates letters, emails, books, pictures, songs and rock CDs. He tries to find sense in these remains. He goes over them again and again like someone trying to find the right piece to a jigsaw puzzle, or film a movie with the fragments of a life. Thus, he is given to a drifting search on the other side of a city traversed by characters who always walk along the edge. There are highbrow artists in the making or on the pathways of extinction who survive a decade of excess: the first years of the twenty-first century. La disolución confronts darkness and desire in order to rescue that strange beauty that dwells in the imbalance of love.

Daniel Ferreira: Viaje al interior de una gota de sangre

A small town prepares to elect its beauty queen during the holidays, when a group of armed, hooded men burst forth in a pickup truck and shoot every attendee of the celebration. By means of a chorus composed of the voices of the dead and perfectly orchestrated by the author, the reader is able to reconstruct the horror and the injustice of one of many massacres carried out by paramilitary groups in the small towns of Colombia.

Carlos Fonseca: Coronel Lágrimas

High in the Pyrenees, an old hermit is consumed with the work of writing a coded universal history. What is he hiding? Guided by the obsessive yet playful eye of its narrator, Coronel Lágrimas traces the unveiling of this vital secret. It shares, in a certain way, the capricious ambition of its protagonist: to reduce the world to a few quotes, some pictures, and a few moments—to encode history. And so, the narration of an arbitrary day of work in the life of the enigmatic main character gives way to an essential mapping that ends up elucidating, in tragicomic code, the political history of the past century. From Russia in the age of the October Revolution to Mexico in the twenties to the Spanish Civil War and the far-away Caribbean, this novel sketches the life of man that was not made for his time. His is the epoch of the private man, and his history is that of a society condemned to computing whims.

Damián González Bertolino: El increíble Springer

Near the end of the nineteen-fifties, when Punta del Este is still little more than a rural dock, two boys begin a nearly instantaneous friendship, becoming inseparable over the years. This continues until one of them is hospitalized with an elusive medical diagnosis, an imprecise clinical anomaly that will change everything. El increíble Springer tells a story, in turn, of transformation: two boys who enter adolescence in an unpredictable manner, in a process that simultaneously plays the chords of the sinister and the familiar.

Sergio Gutiérrez Negrón: Palacio

A young man receives an email from his wife two years after her disappearance. A woman complies with the irrational desires of an old Japanese ornithologist battered by mourning: reading him the diaries of his deceased daughter in a room of birds. We also find a friend who listens closely to the story from the margins and a young jazz trumpeter who observes all from the dais. Between these coordinates, a search begins in which the truth and melancholic imagination are confused in order to conform to a twisted panorama, worthy of that ungodly present where everything is lived secondhand and long-distance.

Gabriela Jauregui: La memoria de las cosas

“The world is a moving knot. The word ‘mundo’ (‘world’) also contains the word ‘nudo’ (knot). The movement of this knot is translated until death. Here: the dog unties the shoelaces of the little girl. Is the dog playing? Perhaps fidelity is itself in play. How is it that all of that solemnity could be so easily undone? When the knot moves it is possible for it to be undone. And if someone else undoes it? Destiny.”

Laia Jufresa: Umami

It started with a drowning.

Deep in the heart of Mexico City, where five houses cluster around a sun-drenched courtyard, lives Ana, a precocious twelve-year-old who spends her days buried in Agatha Christie novels to forget the mysterious death of her little sister years earlier. Over the summer she decides to plant a milpa in her backyard, and as she digs the ground and plants her seeds, her neighbors in turn delve into their past. The ripple effects of grief, childlessness, illness, and displacement saturate their stories, secrets seep out and questions emerge—Who was my wife? Why did my mom leave? Can I turn back the clock? And how could a girl who knew how to swim drown? In prose that is dazzlingly inventive, funny, and tender, Laia Jufresa immerses us in the troubled lives of her narrators, deftly unpacking their stories to offer a darkly comic portrait of contemporary Mexico, as whimsical as it is heart-wrenching.

Mauro Libertella: El invierno con mi generación

This is a novel about the initiation rites of a middle-class teenager and his closest group of friends. The nineties, whicih hinge in national and global history, define the biographies of a group of friends; celibate, clumsy, crazy, and brilliant, whose transformation into adulthood is narrated by the author with sensibility and love.

Brenda Lozano: Todo nada

Two extremely opposite characters are the protagonists of this novel: the elderly Emilio Nassar, a renowned physician, and Emilia, his granddaughter, a young student of literature. This is the story of a relationship between Emilia and her grandfather in the last year of the old man’s life. Their experience begins when Emilio Nassar presses on after the departure of his only true love and the young girl ends her first relationship. In the no man’s land that is life, the characters of this masterpiece confront each other. It is written with immense liberty, precocious literary wisdom, and an unbeatable intuition for humor and catastrophe.

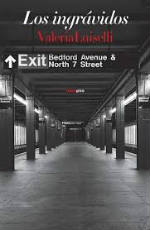

Valeria Luiselli: Los ingrávidos

How many lives and deaths can possibly touch the existence of one single person? Los ingrávidos is a book about ghostly realities: an invocation, both melancholic and full of humor, about the impossibility of the loving encounter and the irrevocable character of loss. It reads frenetically, with emotion that generates an agile, piercing, and oftentimes frankly illuminated writing, without ever abandoning the careful questioning and dissection of the values of the contemporary world. Two voices compose the novel. The female narrator, a modern Mexican woman, tell the story of her early years as an editor in New York, when the ghost of the poet Gilbert Owen followed her on the subway. The male narrator, Owen on the edge of death, remembers his youth during the Harlem Renaissance near the end of the 1920s, where he participated, sometimes reluctantly and sometimes with a happy sense of irony, in the New York literary scene, next to writers like Louis Zukofsky and Federico García Lorca. Both narrators search for each other in the bottomless metro, where they used to travel in their respective pasts.

How many lives and deaths can possibly touch the existence of one single person? Los ingrávidos is a book about ghostly realities: an invocation, both melancholic and full of humor, about the impossibility of the loving encounter and the irrevocable character of loss. It reads frenetically, with emotion that generates an agile, piercing, and oftentimes frankly illuminated writing, without ever abandoning the careful questioning and dissection of the values of the contemporary world. Two voices compose the novel. The female narrator, a modern Mexican woman, tell the story of her early years as an editor in New York, when the ghost of the poet Gilbert Owen followed her on the subway. The male narrator, Owen on the edge of death, remembers his youth during the Harlem Renaissance near the end of the 1920s, where he participated, sometimes reluctantly and sometimes with a happy sense of irony, in the New York literary scene, next to writers like Louis Zukofsky and Federico García Lorca. Both narrators search for each other in the bottomless metro, where they used to travel in their respective pasts.

Alan Mills: Hacking Coyote

Good-bye, rational culture! Let Guatemalan writer Alan Mills welcome you to the philosophy of tricksters. Follow him on a tour through indigenous mythology, classical education, and the literary canon, thoroughly mixed with hacking theory and with popular culture—from Star Wars and Breaking Bad to familiar figures like Bugs Bunny and El Zorro. Get to know Michael Jackson and David Bowie, Guy Fawkes and the Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the Maya-K’iche’, through this fulminant essay on old and new strategies for resisting superpowers. Or, in the author’s own words: “This open-source codex seeks to unite the contemporary traffickers of information with the smoke signals of their totemic animal.”

Emiliano Monge: Morirse de memoria

One morning a man awakens in his bed and wonders, “What did I dream such that I am waking up asking myself who I am?” So begins this wildly twisting psychological novel that brings every aspect of reality into question. The man becomes a passenger on a path of delirium, unable to determine what is real and what is not, even doubting the existence of his brother, his ex-wife, and his pets. Provocative and fantastic, this book explores the depth of memory: the events that escape it and those which remain there forever, willingly or unwillingly.

Mónica Ojeda: Nefando

The experiences of the players are now the center of debate amongst gamers on the deepest forums of the deep web, but the users do not seem to agree. Was it a freaky horror game, an immoral scene, or a poetic exercise? Are the guts of that space as deep and twisted as they seem? Six young people share an apartment in Barcelona. In their rooms, such turbid and disturbing activities develop that they could have been written in a pornographic novel. The frustrated desire of self-castration or the development of designs for the demo-scene appears alongside the artistic technological subculture. In their private spaces, territory-spanning physicality, mentality, and childhood are explored. Spyholes facing toward the heinous connect them to processes of creation for a cult videogame.

The experiences of the players are now the center of debate amongst gamers on the deepest forums of the deep web, but the users do not seem to agree. Was it a freaky horror game, an immoral scene, or a poetic exercise? Are the guts of that space as deep and twisted as they seem? Six young people share an apartment in Barcelona. In their rooms, such turbid and disturbing activities develop that they could have been written in a pornographic novel. The frustrated desire of self-castration or the development of designs for the demo-scene appears alongside the artistic technological subculture. In their private spaces, territory-spanning physicality, mentality, and childhood are explored. Spyholes facing toward the heinous connect them to processes of creation for a cult videogame.

Eduardo Plaza: Hienas

Hienas speaks to us from dizziness about a state of affairs: the province is a tired, abandoned place, inhabited by debris and blurry memories. The narration of the scene is a resistance to the routine of modern life, with stories that establish dialogue about fading moments, about stories that hardly end. We meet actors without a trace of heroism, beaten and broken down, fugitives from the curse of the story that encloses them.

Eduardo Rabasa: La suma de los ceros

Villa Miserias is a generic city in an undetermined Latin American country, and Max Michels is a man confronted by power and its new ideology: quietism in movement. He is a man locked in perpetual argument with every form of authority, with the love of Nelly López and his own mind, as well as his own abundant demons. The lies of modern society are exposed and dissected, along with the eternal sacrifice of the individual upon the altar of new gods.

Felipe Restrepo Pombo: Formas de evasión

Who has not dreamt of being a different person? Victor Umaña, a tormented man, has always had an impulse to disappear without a trace. An anonymous witness becomes obsessed with his story and begins a pursuit that will cause him to search out the clues that his subject has left scattered in various countries. The narrator of this story begins his journey with a bit of shocking mischief, riddled with dark phases. His investigation brings him face to face with violence both public and private that has always been a curtain in the backdrop of Umaña’s existence.

Juan Manuel Robles: Nuevos juguetes de la Guerra Fría

From New York, Iván Morante remembers – or believes that he remembers – what his childhood was like as a pioneering student in the Cuban embassy in La Paz. Guevara’s guerrilla warfare, the Soviet program, and Havana’s interference in Latin America form a colliding force with the promes and fantasies of another form of imperialism emanating from North America. One day, Iván begins to remember and cannot stop doing so: his childhood is, on one hand, a political fiction novel that takes place in the waning days of the Cold War, when the Berlin Wall is about to fall, and on the other, a story of initiation in which an adult tries to be an adult while considering the path on which he reached this point.

Cristián Romero: Ahora solo queda la ciudad

To the ruined and desolate cities are added old gothic mansions, metro cars, dark forests, psychiatric refuges, lost corners, and atmospheres rendered ambiguous by their lack of definition and sinister by their proximity. An irreality invades and takes over the familial and personal spheres, which clearly and certainly exist there – perhaps truthfully. In these stories, innocent in their manner of relating events, something is showing and giving place to the atrocity, the threat, and —why not?—to the marvellous behind an appearance that guards or hides the human element.

Juan Pablo Roncone: Hermano ciervo

Hermano ciervo is made up of eight stories in which the imaginary human and animal mingle. Through a fragmentary narration, with some stories constructed from mere echoes, reflections and inversions, Roncone evokes the lives of characters who, in the words of Chilean film director Alberto Fuguet, in another time “… would cause terror” but that “reading today, right now, at the same time that they were written, are like walking on the metro.”

Daniel Saldaña París: En medio de extrañas víctimas

Rodrigo is a young bureaucrat that could belong to what Strindberg called “the club for young old men.” His days pass without incident in a museum in Mexico City, until the secretary who complicates his life slips him a note that says, “I accept.” Rodrigo will later learn that someone has proposed marriage to Cecilia in his name, and that the inertia of the matter leaves him with no alternative but to marry her. From there, a sinister odyssey is triggered in which he loses his job and passes the time spying on a hen that wanders around a plot of barren land. Meanwhile, a Spanish academic and writer travels to Los Girasoles in order to inquire after a misterious writer, boxer, and artist who found in Mexico that which he searched for his entire life: a tragic ending to match his megalomania. Los Girasoles becomes a center in which the lives of the characters find their destinies between the most absurd accidents and comical, implausible situations.

Samanta Schweblin: Fever Dream

A young woman named Amanda lies dying in a rural hospital clinic. A boy named David sits beside her. She’s not his mother. He’s not her child. Together, they tell a haunting story of broken souls, toxins, and the power and desperation of family. Fever Dream is a nightmare come to life, a ghost story for the real world, a love story and a cautionary tale. Samanta Schweblin creates an aura of strange psychological menace and otherworldly reality in this absorbing, unsettling, taut novel.

Jesús Miguel Soto: El caso Boeuf

Matías Parra has spent years building a useless collection of objects retreived from his walks around the university. As he waits for inspiration that does not come and a work of art that he is not capable of producing, he meets the eccentric Baltazar Boeuf, a professor who has never given clases and who proposes to disseminate a literary artefact inspired in some twisted way by composition. With an apocryphal book as a backdrop, this novel and its dark humor oscillate between the detective and the parodic. It straddles the essential euphoria of senseless projects and the tedium of daily life.

Luciana Sousa: Luro

“We go out in single file, the three of us. Julio goes first, with the food. Sánchez follows him. He holds the bag of clothing close against his chest. I go last. I carry the bottle as a symbolic gesture. The sun shines on my white blouse and I make a shadow in front of me with my hand. I think that he should have a short name, like Raúl, or Juan, but African. I would give a short name to my son. I am thinking about this as I pass by Sánchez, who has stopped. Julio did so first. I drop the bottle and it falls heavily to the ground. Just then I realize that the door to the women’s restroom, with its old-fashioned image of a woman, is wide open. There is nobody inside.”

Mariana Torres: El cuerpo secreto

In this book, innocence, cruelty, and pain reside together in a single body. Mariana Torres invites us with this astonishing premiere to enter into a hybrid world, where the protagonists of the stories are pained children who move between boxes, shells and coffins. How much of us remains in these feeling children? The invitation is clear: to read and to let go, returning as a convert. The stories flow from one to another in an almost exact manner, measured so as to draw in the reader’s mind—or even more, the reader’s body—a concrete emotion that does not have any single name. It is all of that which can grow inside of us like a plant.

Valentín Trujillo: Jaula de costillas

A runaway horse that literally throws the tranquil life of a laborer to the ground, a recently-divorced policewoman who kills a man while following the law, a couple that projects their conflicts onto their pets, a penniless chef, and a crude retelling of the Revolution of 1904 are just a few of the stories that make up Jaula de costillas. Written within the scope of a realism with abundant sensory description and details that appear trivial at first, the stories form a heterogenous group that is united by the language that defines the tradition of the North American “tough writers.”

Claudia Ulloa Donoso: Séptima madrugada

“Like everything, it’s as easy as one, two, three: one of my favorite bands is called Madrugada. The early morning (“madrugada“) is the time of day when I write the most and feel the best. I fall in love with the early hours in the day and I fall out of love with sunlight. I enjoy the sound of its syllables when put together: ma-dru-ga-da, almost like man-drá-go-ra or men-dru-go. In the early morning, I can formulate a strategy to resolve the impossible. I always wanted to write a book entitled ‘madrugada‘, but the title ‘madrugada‘ for a blog was already taken. I put ‘séptima‘ because I have always liked the number seven (7). It’s also because, if you add an ‘N’ to ‘siete‘ it become ‘siente‘. (Ah. Writing about God’s sleep came to me because I couldn’t sleep for almost a whole week. Learn to understand and forgive my offenses).”

Diego Zuñiga: Racimo

The disappearances of several little girls in Alto Hospicio in Northern Chile perplex the protagonist of this novel, a photographer names Torres Leiva, as does the turbid indifference of the authorities. Surrounded by ineffective police, opportunistic politicians, unreliable colleagues, and desperate but sometimes heroic family members, Torres Leiva becomes immersed in a horrifying scene, as severe as the desert in which the events transpire. At the same time, his own life gives the impression of falling into pieces. Written with finesse and precision, Racimo, the second novel by Diego Zuñiga, is an intrigue full of resonances and unforgettable scenes that confirm the author as one of Chile’s most solid and captivating young voices.

Edited and translated by Michael Redzich