poetry is dead

Ezequiel Zaidenwerg

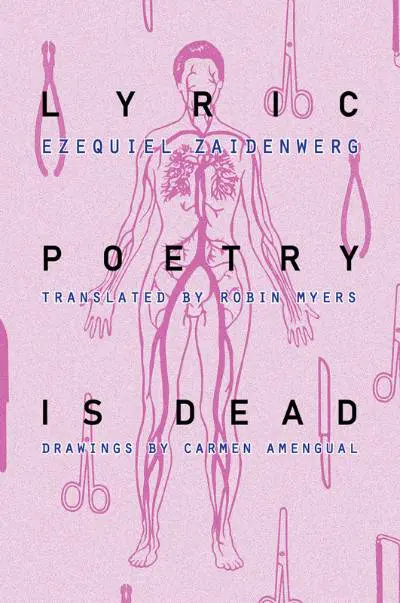

Lyric Poetry Is Dead

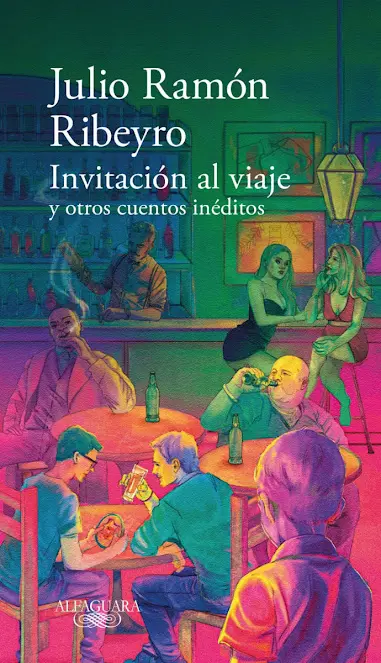

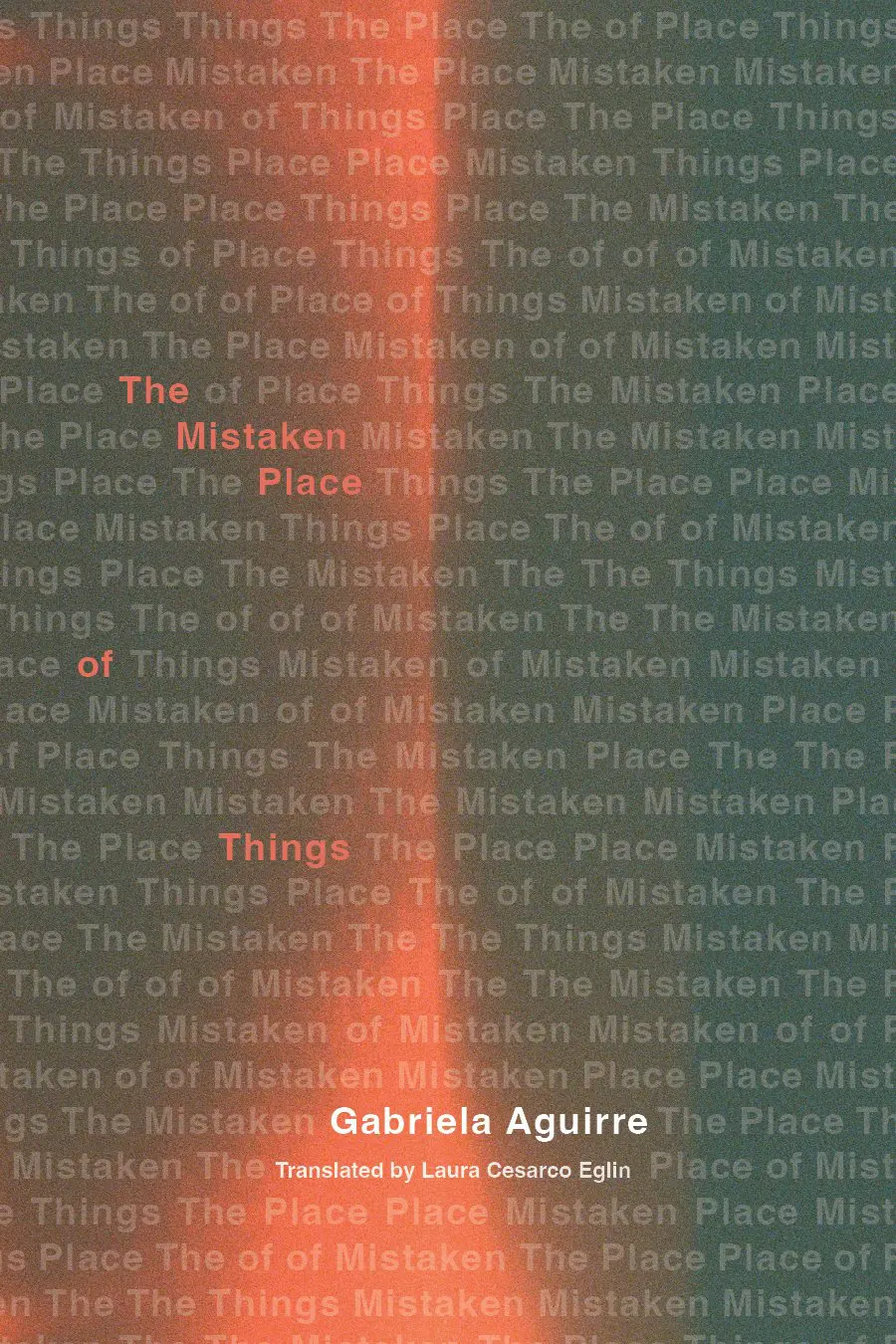

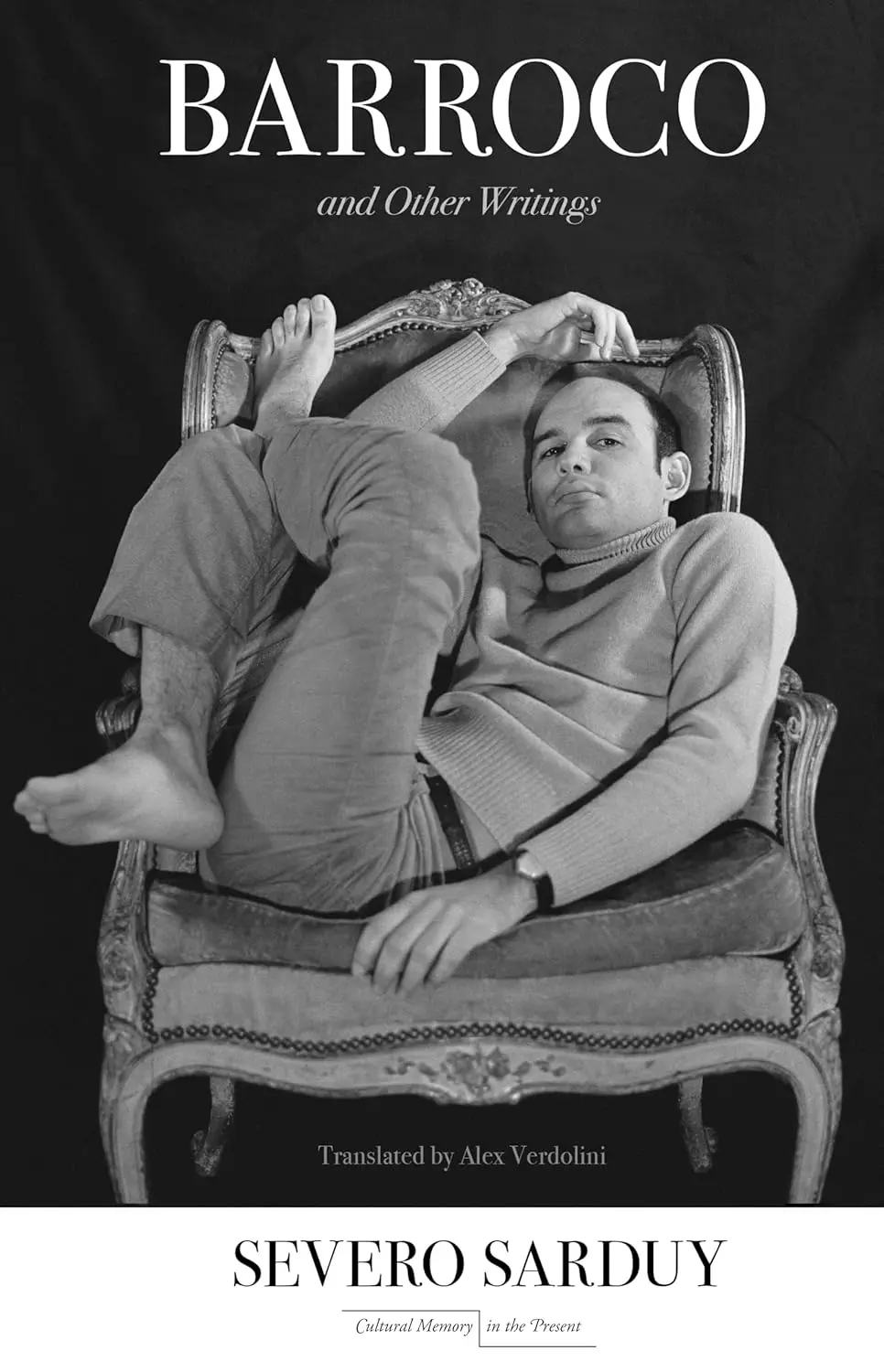

Lyric Poetry Is Dead. Ezequiel Zaidenwerg. Translated by Robin Myers. Illustrations by Carmen Amengual. Arizona: Cardboard House Press, 2018. 128 pages.

For many years, attempts were made to define what has been conceptualized in Latin American contemporary poetry as neobaroque, given that the atypical trends within this last concert of voices have been limited to strange and countercanonical manifestations. I will not stress this problem in this brief commentary; instead, I will list some of the paths travelled by contemporary poets, such as the one that has gathered us here.

For many years, attempts were made to define what has been conceptualized in Latin American contemporary poetry as neobaroque, given that the atypical trends within this last concert of voices have been limited to strange and countercanonical manifestations. I will not stress this problem in this brief commentary; instead, I will list some of the paths travelled by contemporary poets, such as the one that has gathered us here.

Lyric Poetry Is Dead, as rendered in Robin Myers’s careful translation, is a controversial book from the onset. What kind of poem does Ezequiel Zaidenwerg make reference to? Although my intuition is biased, I can say that one of the strongest trends within Latin American poetry is the ultralyricism we inherited from Octavio Paz. The followers of this trend are countless, and it is not my intention to create a consensual record of them. However, I will say that this type of poem is proposed with an apolitical and atemporal immanentism, and that is how this book differs. Lyric Poetry Is Dead is composed of two sections. The first is a homonym of the title, and it covers thirteen poems; the second section, which is actually a single poem, is titled “What Love Does Unto Poets.” The collection includes explanatory notes, in much the same way an investigator in a crime novel leaves clues to mislead or shed light on the case for us, and I can also think of the book as a “case” rather than a path because it prompts one to ask oneself if there exists a single path or if there is the logical or legal presumption of attending a trial here, rather than a book of poems.

This nonpath begins by showing a sickly, moribund body (lyric poetry), but one that is associated with “judicial onslaughts” (12), “has the case been closed” (12), and “final liquidation of the estate” (12). That monstrous dead body highlights its rejection as an inheritance. Perhaps it is also the rejection of a certain type of political poem in the vein of Neruda or Gelman. The second poem, “The Slaughterhouse,” is a periphrasis of one of the foundational texts of Argentine literature (The Slaughterhouse by Esteban Echeverría) and of another text as well, which pays a veiled tribute to the former (El niño proletario [The proletarian boy] by Osvaldo Lamborghini), combined with other references to Argentine soft porn. In Zaidenwerg’s work, the use of all these references is not made in a bookish manner nor as an appropriation of popular culture, but rather as if it were a script setting out the actions of a rape. One cannot help but think about tortured and missing bodies, dirty war, war of the senses, policing of the senses that is always elusive, a musical escape. But also words, arpeggios, files that go missing, even though they vibrate on the patina of the text, an oblique text, but by no means less accurate or transparent within its opacity because of that. Other bodies appear and seek to see us without our noticing them: a mafioso, Perón, Che Guevara. Paradox: these last two corpses had their hands amputated; it is as if these undead might return, and those hands are symbols of action and of the potential writings and of the fear of that act and/or exaction. Regarding the text “Dr. Pedro Ara,” we are told in the notes at the end of the book that it “is a versification (in hendecasyllables in the Spanish original) of a passage from the book El caso de Eva Perón.” Double restriction: transforming prose into metered verse and changing the body/corpse of Evita into lyric poetry. Again, one would have to wonder about this body/corpse that runs through the text. Zaidenwerg uses tropes of traditional poetry and breaks them like someone who is rummaging, like an investigative poet. Before continuing, it should be said there is a verse that is repeated in all the poems, “Lyric poetry is dead,” and that the corpses are lyric poetry and in turn social decomposition. The quotes and explanatory notes can be thought of as a nod to Eliot given that the characters and time periods are also intermingled in keeping with the mythical method of the poet who wrote The Waste Land. Zaidenwerg departs from the versification of broken images, as this is not mere culturalism nor a cultural mosaic. At the end of the thirteenth poem lyric poetry is dead, but “She didn’t die like Christ; they murdered her / like Abel” (100). An Abel who could also be called Babel, which is the death of diversity and the presence of divine justice.

The second section, which is scarcely one poem, is a cento that “isn’t tragic: it’s atrocious” (104). Despite the fact that the beginning can be read as catastrophic, similar to the death of lyric poetry, what it provokes is the opposite: it summons hilarity and unbelief. Love as a type of surgery or, following the image of the investigative poet “as Hansel and Gretel flung breadcrusts” (106). Those breadcrusts are the conflicting clues of the Zaidenwerg case or file. At the end of the book, one may think that the story ate all of them, as if this were a movie about cannibal zombies. Ate whom? Zaidenwerg seems to reply, “the bodies/corpses.”

Paul Guillén

University of Pittsburgh

Translated by Isabel González-Gutiérrez

Paul Guillén (Ica-Perú, 1976) is a poet, essayist, and editor. He studied literature at the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, earned a Master’s in Creative Writing at the University of Texas at El Paso, and is currently completing his doctorate in Hispanic Literatures at the University of Pittsburgh. He directs the journal Poetika1 and the blog and press Sol negro.

Isabel González-Gutiérrez is an MA student in Spanish translation at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey. She has a BA in Political Science from San Francisco State University and four years of experience working as a community interpreter and translator.

Visit our Bookshop page to buy books by this author and support local bookstores.