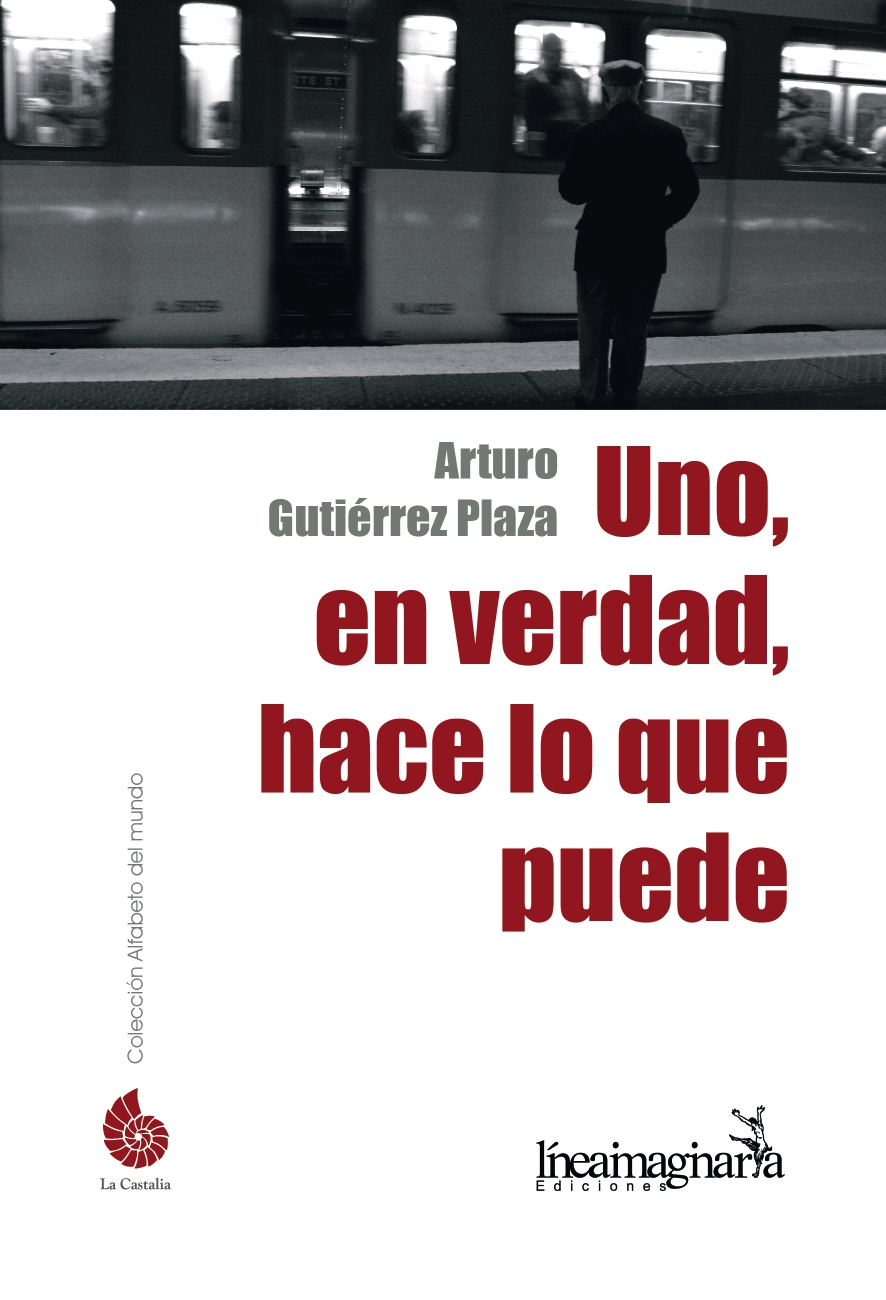

Quito: Ediciones de la Línea Imaginaria/Ediciones La Castalia. 2023. 98 pages.

Uno, en verdad, hace lo que puede is a poetic anthology that gathers sixty poems by Venezuelan author and professor Arturo Gutiérrez Plaza (Caracas, 1962) that were published between 1991 and 2020. The author makes this selection out of poems contained in his previous poetry brooks, published during a period that now spans over thirty years: Al margen de las hojas (1991), De espaldas al río (1999), Principios de contabilidad (2001), Pasado en limpio (2006), Cuidados intensivos (2014), Cartas de renuncia (2020), and El cangrejo ermitaño (2020). In this book, as Gutiérrez Plaza himself states in the preface, the distribution of the poems is more the result of a “progression that is thematic, and perhaps tonal, than of any chronology,” which one notices when reading about memory: the definition of childhood, disease, death, the figure of the family, fixed in parents and children, but also in that local outside revealed in the episodes of a torn country.

Uno, en verdad, hace lo que puede is a poetic anthology that gathers sixty poems by Venezuelan author and professor Arturo Gutiérrez Plaza (Caracas, 1962) that were published between 1991 and 2020. The author makes this selection out of poems contained in his previous poetry brooks, published during a period that now spans over thirty years: Al margen de las hojas (1991), De espaldas al río (1999), Principios de contabilidad (2001), Pasado en limpio (2006), Cuidados intensivos (2014), Cartas de renuncia (2020), and El cangrejo ermitaño (2020). In this book, as Gutiérrez Plaza himself states in the preface, the distribution of the poems is more the result of a “progression that is thematic, and perhaps tonal, than of any chronology,” which one notices when reading about memory: the definition of childhood, disease, death, the figure of the family, fixed in parents and children, but also in that local outside revealed in the episodes of a torn country.

Here, it’s memory and time: the map that allows one to become a poetic protagonist, that which favors the concession of language as revelation. As an image, memory, that unquestionable deposit of doubts more than certainties, is revealed to us as an instrument of time, time that so easily creates that force of will that makes the poet say Uno, en verdad, hace lo que puede [One, in reality, does what one can], a title that, as Arturo Gutiérrez Plaza states, is highly related to the epigraphs he uses as an anchor to present this anthology. Thus, Borges, Brodsky, and Akhmatova argue about the firmness of the text (atemporal, non-definitive), of time, memory, and life, as a recurring habit.

Summarizing, Uno, en verdad, hace lo que puede, in the inventory of a voice that speaks and translates itself as image, as underlined by Miguel Casado in La poesía como pensamiento. In this sense, this poetry is testimonial, confessional, open and intimate, personal and political, for it is about its I and what happens in a Nation, to its citizens.

Thus, Uno, en verdad, hace lo que puede searches, touches the center and margins of a writing conceived for the poetic inside and the real and poeticized outside. That “One,” that testimonial I, brings the reader close to the universe that is contained within him. This book consists of the beginning of a being that recreates itself, that imagines itself from innocence. Meaning, a revision of the existential text: the child who plays hide-and-seek, who plays “dead” with death, as if memory had recourse to the past to continue being: and then, writing, writing from the same childlike vision and arriving at the stones, bearers of silent wisdom.

In the preface to Al margen de las hojas (1991), Gutiérrez Plaza’s first book, the poet warns us about what we have stated:

All writing lingers on the page until it knows its real mission is to be a tattoo of time (…) it is time that the text inhabits (…) All writing learns also, with the passing of every hour, that it is the reader who makes it. He rewrites it in memory: parchment of time, and of life.

Thus occurs the “the fecundation of thought,” which, in reality, the text may accomplish. There are different destinations for this poetry: it doesn’t beat around the bush, hence its title, its daringness, as personal as a whole that amplifies and turns into a mosaic of alternatives: poetry as critique, as moving matter, as a voyage from numerous times and memories. Gutiérrez Plaza moves from infancy, from the most remote presence of a child, that infant “One,” to the multiple poet that speaks of his parents’ illness, of death, of the intensive care in which you see the circulation of pain, anguish, sadness. It is a vibrant echo that the poem brings forth; the entire book is translated by the reader during the same voyage through the biography of a man who uses words to conjure himself away, to alleviate the burden of memory or to render it denser, stronger, more of a presence.

“Gutiérrez Plaza reveals himself in two visions: the one who ceased to exist and the being he now is”

One, once again, multiple, travels around a chronology (the poet won’t accept it) through memory in a single book poured into seven mysterious parts that are forged in this anthology. On several occasions, the poet has said “goodbye,” he has rid himself of the armor of poems to pronounce the final word, that which closes time and memory, to place a farewell, in a demonstration that the passing of days, months, or years is finite, that only memories remain as floating, active, movable, living.

That term, “goodbye,” settles its strength, for example, in the poem “Memoria de una antigua amistad,” in which the author narrates events, feelings endured by his country, by people who were once close to him. A country where family ties and friendships were broken, where violence and hate turn like a dizzying carousel about to be derailed, but there remains, nonetheless, the idea that, “cuando cesen los batallones” [when the battalions cease], we could return to a dubious normality.

That goodbye is also time and memory. The poem becomes tense when spoken. There is no rest: the poet is in it while he thinks it, while he times it or remembers it. No poem is forgotten: it is a changing course or trajectory, a change of landscape, but it remains the image of the poem: from the beginning, from its alpha, from childhood on to times to come, the omega that will arrive, in the word “goodbye,” that overwhelms the author.

That tension involves a state: language inhabits that tension. A poetic genre spans that “One” that affirms a truth, that is, that does what it can: poetry unfolds, it is another from within itself: it is One and a reflection, it orbits around itself with a different tone. The reader multiplies it from the different points of view of the voice that speaks it.

That tension is thought, expanding in an ambivalent territory: Gutiérrez Plaza reveals himself in two visions: the one who ceased to exist and the being he now is. But we can affirm that there is a sort of polyphony coming from the “One” that becomes many through the themes the poet approaches.

The stable being of the one who writes merges with that different poem that will be, in reality, a reading that may bond with the reader as creation. And it is achieved: memory and time have succeeded.

Translated by Oscar Gamboa Duran