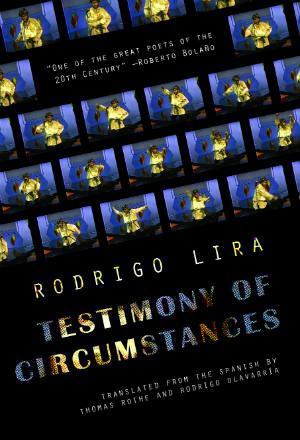

Testimony of Circumstances. Rodrigo Lira. Trans. Thomas Rothe and Rodrigo Olavarría. Phoenix: Cardboard House Press, 2018.

Rodrigo Lira’s poetry inhabits a liminal space between fantasy and “real life”, parodying and deconstructing the imaginary distance between the two. This is particularly true since the myth of Lira as literary bad boy, schizophrenic subject (who would take his life on his 32nd birthday), and fierce satirizer of the Chilean poetic scene, tends to eclipse the body of work by this poet without obra (at least during his short time on Earth). Thomas Rothe and Rodrigo Olavarría’s dazzling translation of poetry by one of Latin America’s most notorious writers expertly renders Lira’s outrageous wordplay, capturing his ludic and often brutal examination of the two things that attracted his lyrical eye: Chilean poets and Rodrigo Lira.

Rodrigo Lira’s poetry inhabits a liminal space between fantasy and “real life”, parodying and deconstructing the imaginary distance between the two. This is particularly true since the myth of Lira as literary bad boy, schizophrenic subject (who would take his life on his 32nd birthday), and fierce satirizer of the Chilean poetic scene, tends to eclipse the body of work by this poet without obra (at least during his short time on Earth). Thomas Rothe and Rodrigo Olavarría’s dazzling translation of poetry by one of Latin America’s most notorious writers expertly renders Lira’s outrageous wordplay, capturing his ludic and often brutal examination of the two things that attracted his lyrical eye: Chilean poets and Rodrigo Lira.

Lira’s verse is a brutalization of Nicanor Parra’s antipoetic lyric voice: he employs a very direct poetic discourse combined with incredibly adept puns and hermetic literary references in order to create a “parodic machine,” as scholar Marcelo Rioseco has convincingly argued. For example, in the Neobaroque or Oulipo-inspired “Ess Tee Pee,” Lira explores the relationship between sound and sense in a sexualized, trance-like, paranoic poem in which nearly all words begin with S, T, and then P, in that order. This constraint is in part a satirical operation let loose on the hermeneutics of poetry and part ludic orgy of signifiers. In the case of poems like “Ars poétique”, “Ars poétique, deux” and “Superpoet Zurita,” Lira ruthlessly mocks and subverts established poetic discourses from the Chilean avant-garde and neo-avant-garde. In his own ars poetica Lira crafts sharp parodies of Vicente Huidobro’s own modus operandi: where his precursor wrote that “Let poetry be like a key/ that opens a thousand doors/…True vigor/ resides in the brain,” Lira implores: “Let verse be like a picklock/ To break in and steal/…True vigor resides in the pockets/ it’s in the checkbook.” Lira is a well-versed “thief” indeed: he “lifts” or “purloins” quotations, bureaucratic formulas, and fragments of texts in several languages. In these verbal collages, digressions, notes and epigraphs, Lira’s poetic masks appear to be infinite. He mocks Nicanor Parra’s famous dictum about the roller coaster of Chilean poetry and about the poets who descended from Olympus, arguing that “…as far as the author/ of these words is aware,/ no one has been treated/ for oral or nasal hemorrhages” and “poorer poetry still is/ the paradise of the solemn fool;/ poets ‘came down from Olympus’/ tumbling over the edge/ until rescue/ corps caught them/ in some Sunday supplement of EL MERCURIO [the major Santiago newspaper]/ or in cultural events/ or in pathetiquette without path….”

In the eponymous poem “Testimony of Circumstances,” the reader finds Lira’s literary suicide, or, possibly, the experience of suicide as literature (whereas in nearly all critical writings on Lira, the reader finds a retrospective biography of (a) suicide). The long poem’s dramatis persona is indeed a verbal prestidigitator or performer; Lira carnivalizes mental illness, licit and illicit drugs, the Chilean legal system, literary prizes and contests, cosmology, capitalism, interpersonal relations (especially with women), daily life and the afterlife. His exhibits his “truths” in a very ambitious poetic wager:

I would like to show something

of certain noninfectioned, noninfected phrasongs

of certain expectanxiousness and honestuttering injurideas

—noncaved or with cavitieafflicted concavities

but regardless, nonvexing

of certain open pit operlyrications,

impeacefuling—ananesthetized—scribbling to my written screams

from this side of the shadows,

season diseason inferno, coldialects, pseudospring

verafreeze, stallion, wheel, cross…

This complex stanza, replete with puns and portmanteau, melds dialects and illness, Neobaroque surfaces and stutterings, and poetic composition. Here, humor and/as irony and parody are subversive machinations “bearing witness” to the difficult situation of one Rodrigo Lira and his place in the pantheon of Chilean poets. In the end, Lira’s poetry is ingeniously aggressive and pathological (as in pathos). If “poetry ended with me”, as Lira would fiercely assert—drawing on Huidobro, Parra, and Enrique Lihn as precursors to be mocked (and also adulated)—Rothe and Olvarría’s sharp translation of Lira’s “operlyrications” upon words, Chilean literature, and upon his own psyche beautifully reports on the situation of this notorious poet.

Scott Weintraub

The University of New Hampshire