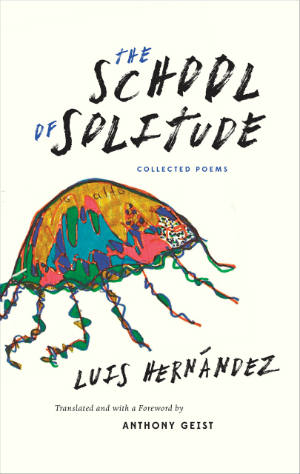

The School of Solitude. Luis Hernández. Trans. Anthony Geist. Chicago: Swan Isle Press, 2015. 167 pages.

Gran Jefe un Lado del Cielo. Luis Hernández. Edición de Luis Fernando Chueca. Madrid: Esto no es Berlín ediciones, 2017. 174 pages.

The recent publication of two anthologies of poetry by Luis Hernández shines a light on an essential voice of Peruvian poetry from the mid-Twentieth century that had previously been largely ignored. Belonging to the so-called Generation of 1960, which includes other important poets such as Antonio Cisneros and Rodolfo Hinostroza, Hernández renewed Peruvian poetry at the time, endowing it with a new and audatious expressive vitality.

The recent publication of two anthologies of poetry by Luis Hernández shines a light on an essential voice of Peruvian poetry from the mid-Twentieth century that had previously been largely ignored. Belonging to the so-called Generation of 1960, which includes other important poets such as Antonio Cisneros and Rodolfo Hinostroza, Hernández renewed Peruvian poetry at the time, endowing it with a new and audatious expressive vitality.

Born in Lima in 1941, Hernández has been a cult figure in Peru for quite some time. The scarce editions of his poetry, his fame as an eccentric, irreverent poet, and his mysterious death on a railroad track outside of Buenos Aires in 1977 converted him into a legend. Delving into his poetry is like playing hide-and-seek, full of riddles and puzzles created by an eternal, mischievous, and iconoclastic young man. A medical doctor by profession, Hernández made poetry, music, and a bohemian lifestyle the linchpins of his existence. Throughout his life, he only published three books of poetry: Orilla (1961) [The Shore], Charlie Melnik (1962) [Charlie Melnik], and Las constelaciones (1965) [Constelations]; but it was enough to captivate a large following of readers and cultivate his legend. In Hernández’ poetry, the city is a recurring image: from his perspective, Lima is an imagined, ghostly place, but it is still recognizable for anyone familiar with the city.

Similarly, the sea is one of this poet’s favorite settings. It’s a background, often foggy to the solitary poetic figure, hurt and melancholic, as seen in “Soy Luisito Hernández” [I am Luisito Hernández]. In Hernández’ poetry, marginality and heartbreak go hand in hand time and again, resulting in a poetic expression that easily moves back and forth between high culture and popular culture. As a result, street language finds common ground with poetic references in Latin, French, or German, similar to the way in which Debussy or Chopin are on a level playing field with a Beatles melody. Such irreverence was misunderstood in the ’60s, but it forged a new expressive path for future Peruvian poets. Such is the case, for example, with “Ezra Pound: cenizas y silicio” [Ezra Pound: Ashes and Silicon], in which the colloquial voice of the poet sends a message to the famous US poet: “Ezra / I know if you come to my neighborhood / the kids at the corner would say: / How’s it going, old man, screw you / And I would die / because in your shadow I would write melodeously / some ideal lines for my oboe . . . .”

Thanks to Hernández’ poetry, youth is lived freely, mischievously, always questioning authority; hence, humor and a playful irreverence that expresses the spirit of rebellion of the ’60s play an important role in his poetic expressiveness. In addition, music is a constant reference that possesses not only the virtue of purification, but also the power of recreating innocence and humanity. Such is the case with “A un suicida en una piscina” [To a Suicide in a Pool], a poem of heightened lyricism dedicated to Brian Jones, a founding member of The Rolling Stones.

Hernandez’ third book, “Constelations,” is perhaps his best achievement. Here, the stars represent the poet’s solitude and narcissism, which are portrayed in an inquisitive, enigmatic, and personal language, one that is rich in expressive power and charged with singular emotion when honoring admirable figures such as Beethoven, Chopin, and Ezra Pound. Despite the poetic maturity of this book and perhaps discouraged by the poor critical reception of his books, Hernández would abandon formal publication of his poetry after this third volumen. Instead, he opted to write in holographic notebooks, using multi-colored felt pens, employing a careful, precise caligraphy, and illustrating his texts with diverse drawings. Since he was prone to giving them away to friends and strangers, it is not known how many notebooks he produced. Some have calculated that some 70 are in existence, which show reiterations of the names of the pianist Shelley Alvarez, Billy the Kid, or the Indian War Lord Next to the Sky [Gran Jefe Un Lado del Cielo], all of whom are the poet’s alter-ego. The common trait among them is their solitude and pronounced sensitivity.

War Lord is probably the most developed character among them. He is characterized by his nomadic existence in the western prairies of the US, his exile in Lima, his contemplative bent, and his powerful tenderness. War Lord loves nighttime and classical culture, and possess a prodigious capacity for contemplation. An ideal complement to this character is Shelley Alvarez, a globetrotting pianist, who is always searching for a place to play his piano and express his love.

Both the bilingual anthology of Hernandez’ poetry, The School of Solitude, finely translated by Anthony Geist, and the book Gran Jefe Un Lado del Cielo [War Lord Next to the Sky], which includes a lucid prologue by Luis Fernando Chueca, are books that merit enthusiastic acclaim. These volumes will not only provide ample access to Luis Hernández’ poetry, but also open the door to original and versatile lyricism worthy of greater critical attention.

César Ferreira

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Translated by Dick Gerdes and Allison Libbey-Titus

Read four poems by Luis Hernández in LALT No. 5.