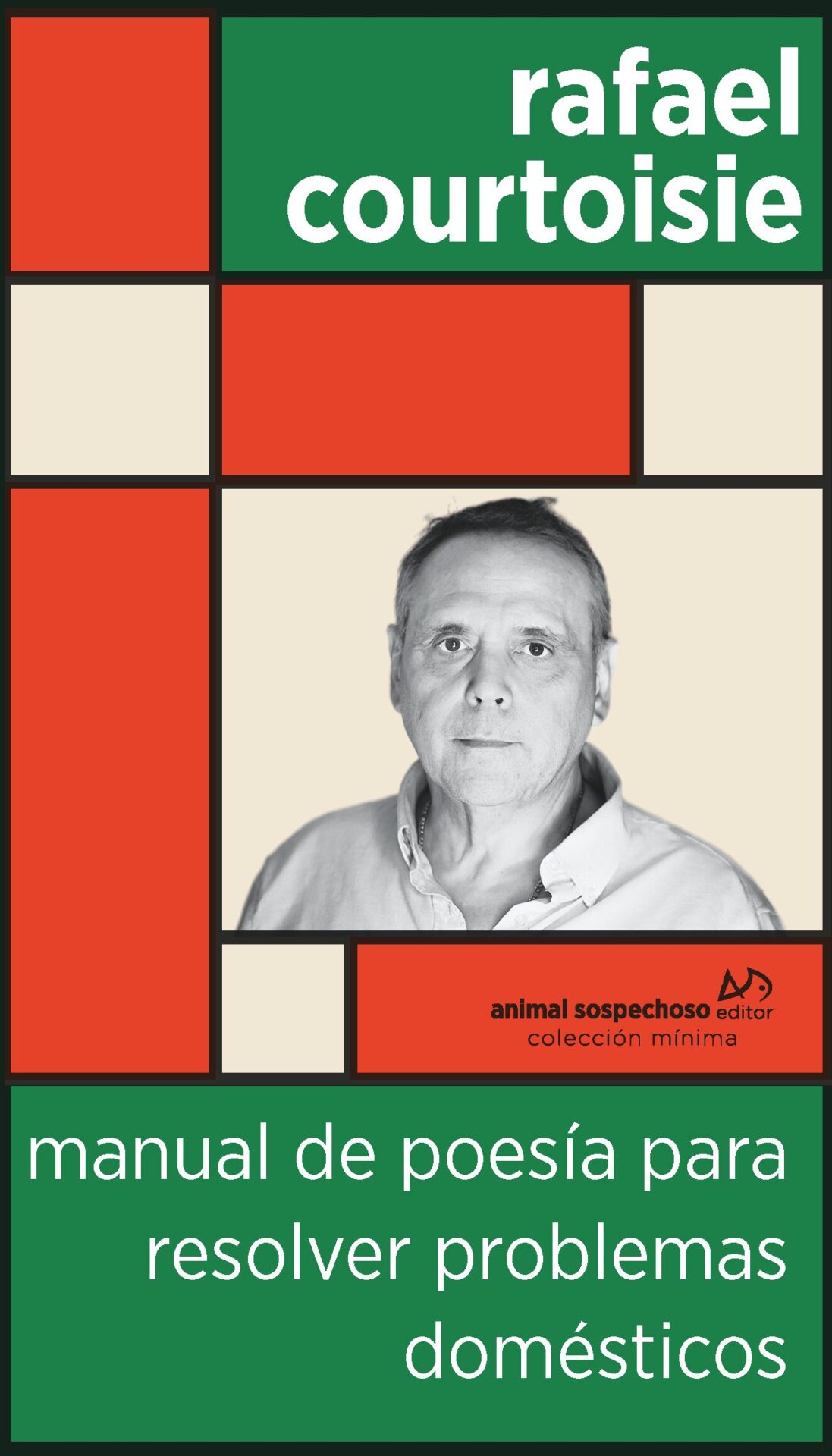

Barcelona: Animal Sospechoso Editor. 2024. 94 pages.

Beginning a review of a poetry book by Rafael Courtoisie leads me to a conviction about his work I have held for decades. Rafael, who once surprised us with the most developed and mature poetry of our generation (he began with Contrabando de auroras in 1977), has, with the passage of time, through his titles and awards—whose juries have included figures such as Octavio Paz and Jamie Sabines—become one of the indispensible voices of contemporary Uruguayan and Latin American poetry. His state of continuous renewal, to put it very close to the indicative title of one of his most “inflexive” collections (Cambio de estado, 1990), has given rise to a powerful dynamic that has never renounced its seductive demand, its rigor, and a reflective thread that is always its autotelic moment. In the trajectory of his poetic work, the poem signals its elaboration as an imperative, wherein it must name itself (whether this process is conscious or not), together with the act of tending to communicability. These two facts, rigor and forms of communicating a world, live united and in harmony in his poetic enunciation. His idea of poetry intensely projected in writing had been related to this consciousness, which, decanting simultaneously with other manifestations of the talent from which it originates, has given rise to different modes of this balancing tension of both phenomena. Even when we face his rich narrative work, which at first may seem so different, it must be said that certain sections and moments of his stories and novels offer a relief close to his poetry.

Beginning a review of a poetry book by Rafael Courtoisie leads me to a conviction about his work I have held for decades. Rafael, who once surprised us with the most developed and mature poetry of our generation (he began with Contrabando de auroras in 1977), has, with the passage of time, through his titles and awards—whose juries have included figures such as Octavio Paz and Jamie Sabines—become one of the indispensible voices of contemporary Uruguayan and Latin American poetry. His state of continuous renewal, to put it very close to the indicative title of one of his most “inflexive” collections (Cambio de estado, 1990), has given rise to a powerful dynamic that has never renounced its seductive demand, its rigor, and a reflective thread that is always its autotelic moment. In the trajectory of his poetic work, the poem signals its elaboration as an imperative, wherein it must name itself (whether this process is conscious or not), together with the act of tending to communicability. These two facts, rigor and forms of communicating a world, live united and in harmony in his poetic enunciation. His idea of poetry intensely projected in writing had been related to this consciousness, which, decanting simultaneously with other manifestations of the talent from which it originates, has given rise to different modes of this balancing tension of both phenomena. Even when we face his rich narrative work, which at first may seem so different, it must be said that certain sections and moments of his stories and novels offer a relief close to his poetry.

His most characteristic feature can be depicted through a spiral in which scenes and objects are recounted in the manner of myth, through which the unexpected refiguration of the images of the world as we know them, in their most prosaic and “communicational” reliefs, takes place. Naturally, the dominant social discourses of public life, as well as those that move over domestic and intimate life in its widest varieties and expressions, are subsumed in the transforming unfolding of a poetic space that stands as a genuine demystifying action. Such an event maintains the decisive drama of a disturbing truth: language is the first reification of the real, so its danger is the promotion of blindness. Courtoisie knows this, and that is why his poetry makes us see again with an unexpected light, which astonishes but does not overwhelm the eye and object of the gaze.

Books so different in the arc of time as Orden de cosas (1986), Cambio de estado (1990), Estado sólido (1996), Música para sordos (2002), Ordalía (2016), and Hacer cosas con palabras (2023) share the paradoxical strategy of definition, which, at the same time, criticizes the finiteness involved in the act of defining. Suddenly we notice that chemical engineering, a profession never practiced by the author, has the capacity to irrigate a trace of its scientific paradigm in this act. Thus, Manual de poesía para resolver problemas domésticos becomes a mature book whose intense brilliance penetrates the abysses of the domus, which is the same as saying of the facts and things of the real, whatever the latter may be, Lacan included.

“Rafael Courtoisie’s gaze disconnects the world from its evidences: it is the work of an eye that deconstructs what language reifies”

The Manual, divided into two parts (the first of which bears the title of the book, while the second is called “Desescrituras” [Unwritings]), and balanced in number of poems, shows in one and the other all that concerns the drama of words both in and with things. The complexity of this development is experienced with surprise by a reader, seasoned or not, who gets to attend to an unpublished display of what he took for granted and known. Consequently, the minimal world of domestic life rises as an irrevocable materiality, in the first part, even from the titles: “Por qué es mejor irse a dormir temprano” [Why it is better to go to bed early] (one of the culminating poems of the book), “Preparativos para los primeros fríos” [Preparations for the first frosts], “Qué hacer ante un grifo que gotea” [What to do when faced with a dripping faucet], “Ordenando frascos en la cocina” [Arranging jars in the kitchen], or “Cuando vayas a reparar un muro” [When you go to repair a wall]. The elemental, the apparently insignificant, what is not “recounted” in the order of the poetic is the unpredictable founding place of the poetry of this book by Rafael Courtoisie. Each of these poems brings up the common, the habitual, the familiar, to gently and radically derealize it, so that we read it as one who must learn to look and understand anew, as one who learns a language of words and perception rolled one on top of the other and vice versa. That is to say, as if the things he makes us see had been invisible to us, blind until this moment. Unfinished and radically enriched in meaning, this “manual” offers its cut and expansion by appealing to a metaphorical becoming of brilliant imagination and mythical vocation—it seeks to become the story that is not told—so as not to close itself in any way, exposing the dimensions of a writing that is much more revelation of the forbidden other than expression and confessionality. It is a poetry of cognitive longing, in pursuit of vision and other traces of knowledge that seems lost. For example, in the poem “Ordenando frascos en la cocina,” that titular jar grows in metaphoricity and evocation, skipping its most plain and expected object-ness, although the domestic remains there, incorruptible, patent and powerful, but in another way:

El de sal encierra la mitad del mar

la parte seca, el recuerdo de la sopa

de la abuela, una pizca sobre las claras

hace que se muestren más sólidas

y enhiestas al batirlas, unos gramos de más

cada día abonan

la hemorragia cerebral:

cuida que no se ahogue en sangre

la voz de tus recuerdos.

[The salt one encases half the sea

the dry part, the memory of grandma’s

soup, a pinch on the egg whites

makes them more solid

and stiff when beaten, a few grams more

each day fertilize

the cerebral hemorrhage:

be careful not to drown in blood

the voice of your memories]

It is known that all self-respecting poetry points to its own elaboration, not as an ornamental resource but because there is no other choice but to show the hollowness of the real through language and take the risk of a wounded word. This is what happens over the course of Courtoisie’s work; however, it should be stressed that it reaches its climax in the present volume: a plateau of creative awareness and risk, of balance and tension, of lyricism and distance, of the protagonism of language as a problem and of the question of things. Hence the sharp accuracy of poem XXII of “Desescrituras,” in which “La parte oscura del lenguaje/ ilumina/ la cara oculta de la vida/ Alumbra al callar” [The dark side of language/ illuminates/ the hidden face of life/ Illuminates in its silence]. This whole second section of the book is a dramatization of that lack and that adventure after some form of epiphany.

In short, this poetry of the minimal that is not minimalist, for it is expansive in its encircling of the thing that is given and vanishes at the same time; that is cognitive, but from a “sensualized” intellection, so to speak; that lends a material flavor to things and to the stories contained or insinuated: it also points out, at times, somber zones of a self that slips away and manifests itself in the midst of this light obtained thanks to the act of writing it. In the excellent prologue, Mario Pera rightly states that, in this collection of poems, Courtoisie creates “scenes described with the delicacy of a goldsmith; for example, how to remove a stain, how to attract a woman’s attention, how to arrange the jars in the kitchen, or repair a wall, or do gardening work.”

Rafael Courtoisie’s gaze disconnects the world from its evidence: it is the work of an eye that deconstructs what language reifies. That is why he needs another language. Thus, he is capable of revisiting domestic scenography with a poetry that revives the oft-forgotten power of the word, against the hiding and fossilization of the commonplace. His is a serene, lucid, and unsettling pursuit, which at times brings us face-to-face with the sinister and that which Rilke regarded as the terrible that we can still endure: the beauty of the poetic through the search for the secret name that every object has, as we read in one of his poems (the reader may find it), from the second part of this book of triumphs.

Translated by Marit Eiler