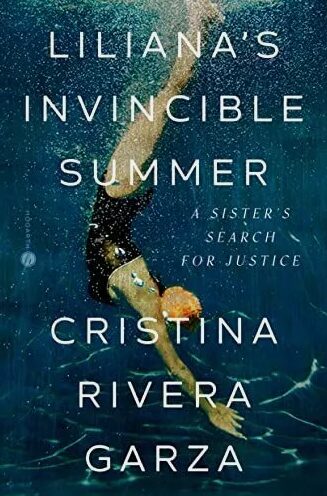

Hogarth Press, a division of Random House, 2023. 320 pages.

Liliana’s Invincible Summer: A Sister’s Search for Justice, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 2024 in the category of Memoir and Autobiography, is the story of a brilliant young woman, Liliana Rivera Garza, who was murdered by her high school boyfriend, Ángel González Ramos, who subsequently disappeared from Mexico and has never been convicted. In 1990, when Liliana was murdered, she was twenty years old. She was living in Mexico City, having moved there from Toluca so she could be near her school, where she was studying architecture. At the time of her death, her family was away from Mexico. Cristina Rivera Garza, her older sister, was studying in Houston and the girls’ parents were taking a long-anticipated trip to Europe.

Liliana’s Invincible Summer: A Sister’s Search for Justice, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 2024 in the category of Memoir and Autobiography, is the story of a brilliant young woman, Liliana Rivera Garza, who was murdered by her high school boyfriend, Ángel González Ramos, who subsequently disappeared from Mexico and has never been convicted. In 1990, when Liliana was murdered, she was twenty years old. She was living in Mexico City, having moved there from Toluca so she could be near her school, where she was studying architecture. At the time of her death, her family was away from Mexico. Cristina Rivera Garza, her older sister, was studying in Houston and the girls’ parents were taking a long-anticipated trip to Europe.

Rivera Garza has wanted to write this book for thirty years, ever since her sister’s death, but on previous occasions when she tried to write it, she failed. After Liliana’s death, in a judicial system that blames the victim and her family, Rivera Garza and her parents were shrouded in shame, in silence. At Liliana’s grave, Rivera Garza writes, “We’re enclosed in a bubble of guilt and shame.” And the question we ask ourselves: “Why couldn’t we have protected her?” The author wanted to write this book because she didn’t want her sister to disappear, but she also felt impelled to rescue her from a narrative where she was considered a victim. She writes to release her sister from stereotypes that contradict each other: A disciplined swimmer. An innocent. Someone with a past, a liar, a woman who is perhaps too free. Not until June 14, 2012, was femicide, the killing of a woman or girl because they are female, recognized in Mexico and incorporated into the Mexican federal penal code. Time had to pass and language had to change to give rise to a climate in which, as María Elena de Valdés writes in The Shattered Mirror: Representations of Women in Mexican Literature, women’s narratives can be received.

The book opens with Rivera Garza, accompanied by a friend, visiting judicial offices in Mexico City: a city that she loves, a city that she says can also kill you. When she first goes to reopen her sister’s case, she is asked what she is looking for; she cannot speak. It has taken her thirty years to say the word: justice. To be able to speak, a change in language has been necessary. In 2019, in a demonstration in downtown Santiago de Chile, the activist group, Las Tesis, appropriated language traditionally applied to women, like Liliana, who have been victims of gender-based violence where the perpetrators have often gone unpunished: “la culpa no era mía / ni dónde estaba / ni cómo vestía” [“It wasn’t my fault / nor where I was / nor what I was wearing”].

“Rivera Garza learns that González Ramos had been paying the drug addicts in front of Liliana’s apartment to keep him abreast of her comings and goings.”

Also, after thirty years, Rivera Garza opens the seven boxes and four wooden crates containing her sister’s possessions—boxes which have been stored, unopened, in their parent’s house. The boxes contain drafts of Liliana’s letters to her cousins, her high school girlfriends, and her friends at university, in Liliana’s meticulous print, all of which Liliana has archived. Rivera Garza says of her sister, “Liliana was the real writer of the family.” She traces Liliana’s last winter from the notes, the Scribe notebooks with graph paper that Liliana favored, the writing on scraps of paper, napkins, drafts of letters she never sent, transcriptions of poems, lyrics of songs like those sung by the Cuban singer Eugenia LeónL “Porque digas lo que digas/ ya soy parte de tu vida / y contra ti no has de atentar” [“Because say whatever you want / I am already part of your life. / And you cannot attack yourself”]. A young woman who wrote “assiduously until the last day of her life.” Who still loved Hello Kitty stickers. With the help of her husband, Rivera Garza has also interviewed Liliana’s university friends. And it is through these testimonies, as well as Liliana’s own writing, which beautifully recreate that time, that we learn about Liliana and her world. As if the present when Liliana would arrive for her classes at the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana in Azcapotzalco never disappeared.

The epigraph of the first chapter of Liliana’s Invincible Summer is a line from the poem “Límite” by feminist writer Rosario Castellanos: “aquí, bajo esta rama, puedes hablar de amor” [“here, under this branch, you can speak of love”]. Castellanos wrote on language as an instrument of domination, a way to separate and divide, to establish control. Machismo has been ingrained in Mexican culture in a way that has defined both men’s and women’s social identity, in a culture where love songs can feature violence. Historically, when a man murdered his intimate partner, the crime would be considered a crime of passion. But when a man kills his intimate partner, there have always been previous incidents of violence, and it is clear from Liliana’s writing that there had been previous incidents of violence. Rivera Garza learns that González Ramos had been paying the drug addicts in front of Liliana’s apartment to keep him abreast of her comings and goings. In Mexico’s political system, where men are disenfranchised, the beings that they have control over are the women in their lives. Liliana’s murderer was one such disenfranchised young man who exercised control over his girlfriend, a young woman who was trying to be free of him, by breaking into her apartment at night and strangling her in her bed.

In the book’s last chapter, entitled “Chlorine,” Rivera Garza tells how she starts swimming again—an activity that the two sisters, high school competitive swimmers, shared. And it is only after she’s been swimming that she allows herself to grieve. And it is only when she injures her shoulder and can no longer swim that she writes this book.