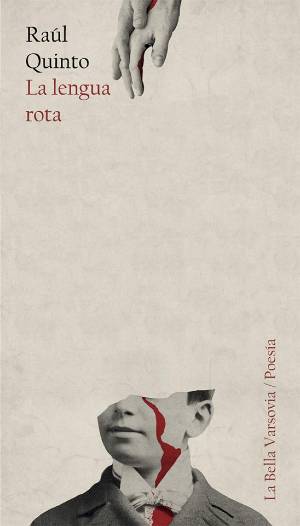

La lengua rota. Raúl Quinto. Madrid: La Bella Varsovia. 2019. 80 pages.

A word, when spoken, is irrevocably tied to the corporeal, material, character, not only of its own signifier, but also of the subject who utters it and the context—social and human—in which it is found and which it interpellates. There is no speech without language; there is no language without humanity. And humanity feels, bleeds, and hurts. Raúl Quinto’s La lengua rota (Cartagena, Spain, 1978) centers around this problematic, dual act of language: it emerges as discourse about the world, yet at the same time is itself an autonomous entity, which in its use conceives reality. This is Quinto’s eighth book, and his other published works include poetry and hybrid prose (Grietas, Dauro 2012; Poemas del Cabo de Gata, La Garúa, 2007; La piel del vigilante, DVD, 2005; La flor de la tortura, Renacimiento, 2008; Idioteca, El Gaviero, 2010; Yosotros, Caballo de Troya, 2015; Hijo, La Bella Varsovia, 2017).

A word, when spoken, is irrevocably tied to the corporeal, material, character, not only of its own signifier, but also of the subject who utters it and the context—social and human—in which it is found and which it interpellates. There is no speech without language; there is no language without humanity. And humanity feels, bleeds, and hurts. Raúl Quinto’s La lengua rota (Cartagena, Spain, 1978) centers around this problematic, dual act of language: it emerges as discourse about the world, yet at the same time is itself an autonomous entity, which in its use conceives reality. This is Quinto’s eighth book, and his other published works include poetry and hybrid prose (Grietas, Dauro 2012; Poemas del Cabo de Gata, La Garúa, 2007; La piel del vigilante, DVD, 2005; La flor de la tortura, Renacimiento, 2008; Idioteca, El Gaviero, 2010; Yosotros, Caballo de Troya, 2015; Hijo, La Bella Varsovia, 2017).

La lengua rota sets outs from and constructs itself around an anecdote from pre-Socratic philosopher Zenon of Elea, who upon being brought to testify in front of a tyrant he opposed, ripped out his tongue in a radically rebellious gesture and spit it onto the face of the oppressor, refusing to say anything: “la lengua está rota y ensucia el blanco rostro del poder. / Y dice.” [the tongue is ripped and dirties the white face of power. / And speaks.] With this sentence, having set the tone for the rest of the work, he begins to reveal its motives. Their poetic and ethical proposal not only avoid being unnecessarily complex in their textual depiction, but are also recognizable from beginning to end in the way he has crafted his book.

The forty-four poems, organized into the sections “La lengua rota” [The ripped tongue], “La carretera invisible” [The invisible road], “Talidomida” [Thalidomide], and again “La lengua rota,” have an abundance of proper names for titles, all of which correspond to activists (men, women, and children) of different causes, places and times, all of whom died violent and unjust deaths at the hands of those powerful enough to commit such brutalities. They include Javier Verdejo, a student and leftist activist murdered at the age of 19 by the Spanish Civil Guard; Salwa Bugaighis, a human rights defense lawyer killed by Muammar Al-Qadhafi’s regime in Libya; and David Kato, an LGBTQ activist who was beaten to death with a hammer in Uganda, just to name a few. The two poems that comprise the second section are called “Málaga-Almería,” in reference to a massacre perpetrated by Francoist troops in 1937. Thalidomide, the name of the third section, alludes to a medication which caused birth defects in infants exposed to the drug as fetuses. The company that produced the drug never faced charges. All of these facts are not detailed in the text itself, but can be found in the appendix.

Through the elucidation of these examples, it is clear that the author wants to be transparent about the political intentions—that is to say, the human intentions—which inform his poems. He entrusts them to the reader in an act of reclamation that seeks to recover silenced portions of history and collective memory, as a sort of reckoning with reality. However, it appears that the merit of the compilation is found in its capacity to stand alone, beyond any extratextual motivation. One of the poems tells us that poetry is a language, and later that “un idioma es un animal que mira y un animal que mira es siempre un mundo entero” [language is a creature who watches, and a creature who watches is always an entire world unto itself]. Through his precise, controlled, beautifully-constructed, rhythmic discourse, full of unconventional and sometimes difficult imagery, his poems communicate beyond that which is readily apparent. The value of La lengua rota, after all, resides in its poetry, the only language possible before an unlikely, lurid, reality.

In full mastery of his craft, far from falling into the ease and neglect that often abound in so-called “committed” literature, Quinto constructs a poetically consistent universe, making use of words which move between the evidently descriptive and the proverbial, which not only observe and tell, but also feel, smell, and experience in a sensory way what occurs in a reality where the distinction between the interior and exterior is blurred. With the tongue ripped and the possibility of speaking with it cut short, everything becomes sensory. The voice becomes a delicate succession of gestures, only to come in contact with the most intimate and seemingly insignificant details of those other bodies that have been silenced. (“los bordes calcinados / tras el oficio de la bala / son un párpado abierto” [the scorched edges / which follow the bullet’s purpose / are an opened eyelid]) or simply disregarded amongst the noise of the world (like that of a butterfly fighting for its life against the glow of a light bulb: “un sonido pequeño y ritual / como de corazón bajo la escarcha. / Un morse susurrando / la estructura de un grito” [a small and ritual sound / like that of a heart under the frost. / A whispered Morse code / the echo of a cry]).

La lengua rota informs us that the inability to speak can become an opening, the possibility to listen once again, to pay attention to that which constitutes and surrounds us, to discover that even in the minute and invisible there is rebellion. It tells us of the organic nature of a fight—one of bodies speaking to each other in their silent intimacy—which continues, repeating its gestures across time like a nameless rhythm, without witnesses in the forgotten corners of the world. It does not stop speaking to us.

Micaela Paredes

New York University

Translated by Ardyn Clayton

Micaela Paredes Barraza (Santiago de Chile, 1993) earned her degree in Hispanic Letters from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. To date, she has published two verse collections, Nocturnal (2017) and Ceremonias de Interior (2019), both from Cerrojo Ediciones, Chile. She is the coeditor of the poetry journal América Invertida, published in New York. She is currently earning a Master’s in Creative Writing at NYU.

Ardyn Clayton is currently pursuing an MA in English-Spanish Translation and Interpretation at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in Monterey, California. She previously attended Lee University in Cleveland, Tennessee, where she obtained a BA in Spanish before deciding to pursue translation and interpretation at Middlebury.