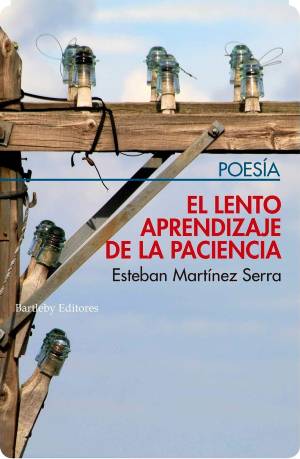

El lento aprendizaje de la paciencia. Esteban Martínez Serra. Madrid: Bartleby, 2019. 134 pages.

Now you will feel the essence of things still.

Esteban Martínez Serra

To read is to understand and to create a particular system of understanding, and to write is to express what has been understood about the world. A point I would like to highlight is that the first poem of a book is the one that provides a framework for a poetics. In this case, “Nota al pie” [Footnote] (pg.17) already gives hints of a reflexive poetics.

To read is to understand and to create a particular system of understanding, and to write is to express what has been understood about the world. A point I would like to highlight is that the first poem of a book is the one that provides a framework for a poetics. In this case, “Nota al pie” [Footnote] (pg.17) already gives hints of a reflexive poetics.

One of the aspects that has surprised me the most about this book, El lento aprendizaje de la paciencia [The slow learning of patience], is the continuous approach to things from different perspectives even within the same poem. How does one speak of death and of the dead? What experience is in dialogue with the word? We believe that these two questions indicate the way in which things manifest themselves as alternative objects of a new experience. All learning is slow; it is herein as well that this book allows itself to be an inverted sign of an epoch—one representative of the rapid, the fleeting, and the liquid.

Inversion and the new perspective of the world also serves as currency in the poems we are presently discussing; moreover, that perspective also has the function of revealing other uses for the poetic word. In this poem we find a new meaning for the object introduced: “El invierno vive mejor/ en las alas del ave migratoria./ Como la fe, lejos de los templos./ ¿Y la justicia? —dime—/ ¿qué hay de la justicia,/ de la que nada dices?” [Winter is best lived / on the wings of a bird that migrates. / Like faith, far from the houses of worship. / And what of justice? —tell me— / what about justice, / of which you say nothing?]

These new meanings are also mere segments of a whole as the poem cannot speak to the experience in its totality which is a convention that always alludes to a relationship with emptiness, but also with the totality of that which has not been expressed but which is always present. We read “En la escritura/ nada debe vaciarse completamente” [In writing / nothing must be emptied completely], that is to say, nothing must be said or nothing is presented with a closed meaning, which does not nullify the profusion of meanings either. And in order to find the approach it is necessary to have patience and an accumulation of experiences regarding the poetic word; we could even include slowness which—as indicated by the title of this collection of poems—is an ineludible schema of knowing. “Hay algo de desmesura en todo lo consciente/ que solo el arte reconviene/ a veces/ con su propio exceso” [There is something of an excess in all awareness / that only art can rebuke / sometimes / with its own excess]. For this book’s set of experiences also reveals itself through excess. However, compared to this, the vast majority of poems seem measured, at times too scant to create that necessary tension between what is stated and what is left unsaid: a tension that ultimately spreads from the now to the then.

On the other hand, these poems are sometimes structured as dialogues where the voice remains silent, where whoever listens is faced with questions or perhaps even a resolution. A series of dialogues residing in a moment of reflection regarding events and actions. What can be said from similitude to quietude? “Alcanzar a ser nada. Regreso/ al lugar donde aún la idea del regreso no existía./ ¿Acaso es demasiada ambición para un hombre?” [To achieve a state of nothingness. I return / to the place where the idea of returning had not yet formed. / Is it perhaps too much ambition for a man to have?]

There is a poem in the third section that forms part of the history of the definitions of love. The poem establishes a dialogue with the beloved and about the reasons behind the possible definition of love, which is to elude the possibilities of multiple declarations of suggestion, characterisitic of poetry. “Me pides que te defina el amor./ Pero los determinantes siempre traen sus recelos,/ un corte de navaja, el borde del precipicio./ Debo entender que no quieres vaguedades, honduras abstractas, terrenos pantanosos./ Tampoco vistas a páramos abiertos./ Quieres saber que sé lo que es “el amor”/ —no “un amor impreciso, adjetival”, insistes—/ y en tu mirada adivino que solo tú sabes la respuesta/ y esa es la razón última de tu pregunta”

[You ask me to define love for you. / But determinants always come with misgivings, / a razor’s cut, a cliff’s edge. / I must understand that you want no ambiguity, no abstract depths, no swampy terrains. / Nor views of open moors. / You wish to know my understanding of what “love” is / —No, you insist on “an imprecise adjectival love” — / and in your gaze I suppose that only you know the answer / and that is the underlying reason behind your question].

As we can see, the game that Esteban Martínez Serra begins between questions and lack of answers appeals once again to the poem’s allusions and self-referential dialogue regarding the various possibilities for the poetic word. We thus see in his poetry an attempt at defining the poetic space, its limits, and its meanings. For the lack of a pronouncement highlights the definitions of love that were requested in the poem just mentioned. Hence, “Quiero tu voz, no las palabras” [I want your voice, not words] is also later stated. Therefore, sound is what is necessary when silence engulfs and sparks the immense awareness of silence.

Throughout the entire book the relationship with words transforms into the relationship between what is thought and what is observed, it is within that space that the series of dialogues we are reading is constructed. “¡No! No seré ninguna estrella yo/ cuando muera. Ningún poro de luz/ en la inverosímil piel del universo./ Ningún pájaro celeste/ me llevará en el pico./ No. No me busques tan lejos./ Seré el charco en la puerta de casa” [No! No star shall I be / when I die. No strand of light / in the incredible fabric of the universe. / No celestial bird / will carry me off in its beak. / No. Do not look for me that far. / I will be the puddle outside your front door]. And amid these indecisions the poems begin to form the relationship between the words and the allusions. Where is the essence of things? Where can we experience the simplicity of words before they are spoken? Once written, words seek meaning the moment they are stated. Things cannot be made to provide the experiences of the word, thus the repetition regarding the inability of the word to no longer be an image, to outlive the words which can no longer describe that which is immediate and which strays from that sometimes natural, sometimes social and urban world. “Arrastro la lengua volcánica sobre tus cosas/ como lo haría un ciego con la palma de su mano/ y no puedo apenas describirlas/ sino en la insípida ceniza que ahora son./ El presente —me digo— no sabe a nada” [I run a fiery language over your things / just as a blind person would do with the palm of their hand / and I can scarcely describe them / save as the bitter ashes they now are. / The present—I tell myself—tastes of nothing].

This book is comprised of 5 sections, with the last section containing 10 colophons, followed by an “afterword” that concludes the volume and resolves the questions that were raised throughout; not unlike a representation of, or the attempt at, representing life through an object that brings together the “least” with the “greatest,” the least amount of space and the greatest number of autobiographical references. References always stored away to reread and rewrite. It is there that the pencil that drew and wrote the first lines during childhood now writes and stores away an ending that never ends, a life that is projected through “miles de biografías posibles con sus centenares de miles de secuencias” [thousands of possible biographies with their hundreds of thousands of sequences].

Lucas Margarit

Department of Philosophy and Literature

University of Buenos Aires

Translated by Isabel González-Gutiérrez

Lucas Margarit (Buenos Aires, 1966) earned his doctorate in Letters from the Universidad de Buenos Aires, writing his doctoral thesis on the poetry of Samuel Beckett. He has undertaken a post-doctorate on translation and auto-translation in the poetry of the same author. He is a poet and a professor and researcher at the Universidad de Buenos Aires. He has collaborated with many publications and has given courses, seminars, and conferences in Argentina and internationally. He has published the verse collections Círculos y piedras, Lazlo y Alvis, El libro de los elementos, and Bernat Metge and the essay collections Samuel Beckett. Las huellas en el vacío, Leer a Shakespeare: notas sobre la ambigüedad.

Isabel González-Gutiérrez is an MA student in Spanish translation at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey. She has a BA in Political Science from San Francisco State University and four years of experience working as a community interpreter and translator.