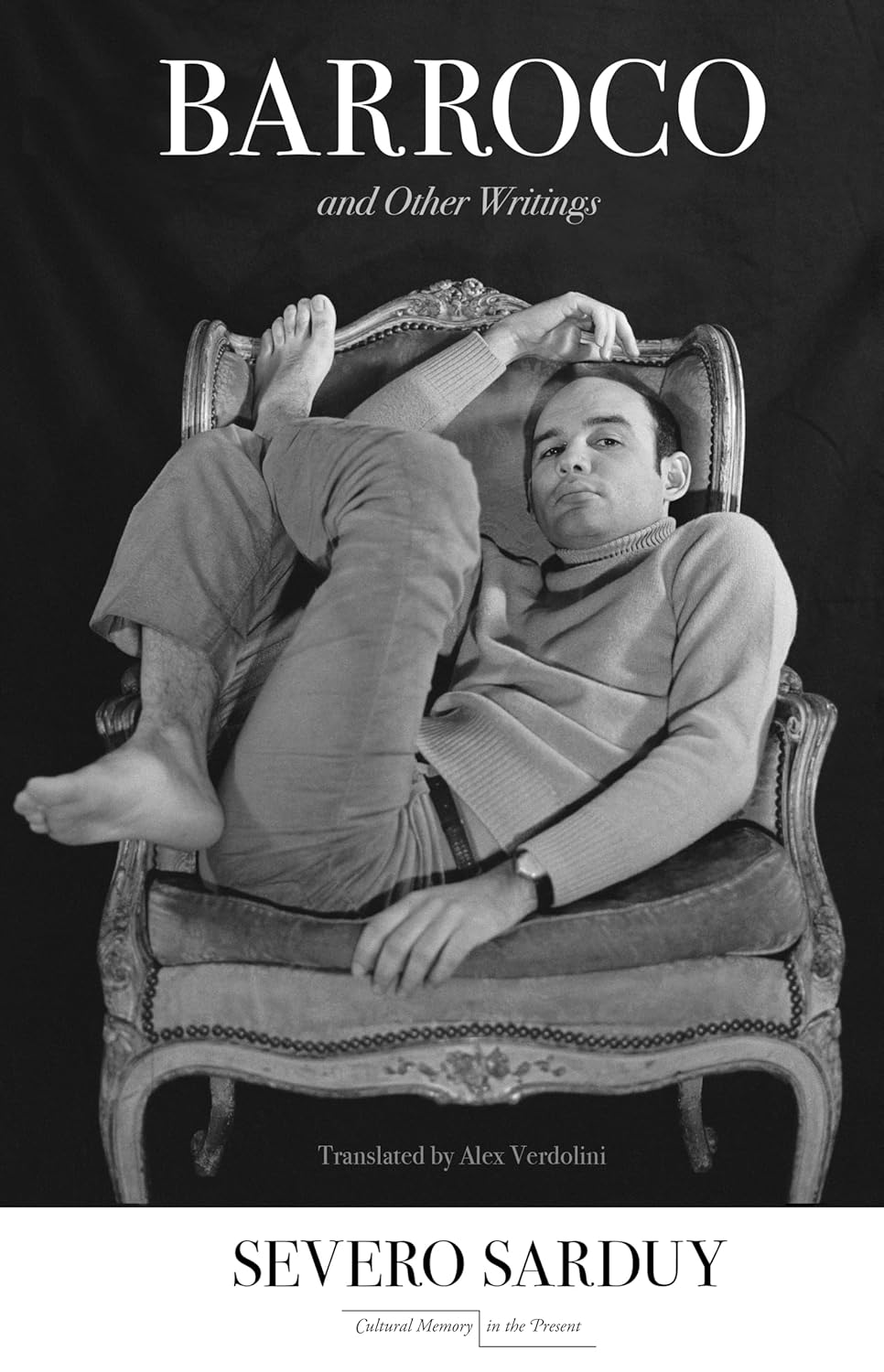

Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2024. 200 pages.

In a time of ubiquitous minimalism, where cannabis dispensaries and coffee shops look like Apple stores; of PhD dissertations that elaborate on niche topics through very specialized lenses, Severo Sarduy’s Barroco and Other Writings breaks out from the grave as a fresh, lively book.

In a time of ubiquitous minimalism, where cannabis dispensaries and coffee shops look like Apple stores; of PhD dissertations that elaborate on niche topics through very specialized lenses, Severo Sarduy’s Barroco and Other Writings breaks out from the grave as a fresh, lively book.

Ornate yet precise in its analyses, this collection of essays on art and epistemics shows us that Baroque isn’t a word relegated to museums and that poetry has a place in theory: not as an object, but as a practice.

Consider the first—or pre-first?—text in this collection, titled 0. Echo Chamber; a wink, perhaps, from an everlasting past to today’s buzzwords. Therein, Sarduy announces that “in this chamber, the echo sometimes comes before the voice.” This sentence not only summarizes the way the Baroque works, per Sarduy’s digressions, but is also poetic of sorts—a statement of purpose the author lays out to justify the style of his writing. Thus, coherently, the Cuban writer finishes this declaration with a conclusion or summary of his ideas—with an echo that precedes an unraveling of words: “In the symbolic space of the Baroque (…) we would find the textual citation or the metaphor of the founding space postulated by contemporaneous astronomy.” And in the literary space of Sarduy’s thoughts, the same follows.

“The question of philosophy is thus the singular point where the concept and creation are linked together,” Deleuze and Guattari once wrote. And certainly, Sarduy’s essays commit to this idea through the concept of retombée, which precedes and frames the essay collection. Defined—in verse—as “achronic causality, / non-contiguous isomorphism, / or, / consequence of something that has yet to occur, / resemblance to something that has yet to exist”—he points out the presence of the retombée in art, science, and everyday practice at the center of the Baroque. Sarduy’s perspectives on the work of Galileo Galilei, Diego Velázquez, and Luis de Góngora become, anchored in this original concept, philosophy in its most creative expression.

“When conservative thinkers and politicians insist on the radical difference between Latin America and the Western world, Sarduy’s book, as the Baroque he describes, today certainly ‘subverts the supposedly normal order of things.’”

It’s particularly relevant that Sarduy insists on astronomy as a source of artistic style—or thought or practice. In a sense, the development of our ways of viewing the role of our world, the way our planet moves in the vast space of the galaxy—literally elliptic, less central and centered as the centuries have progressed—are reflected in the arts. Just as Karl Marx considered culture to be the reflection of the economic conditions of a society, cosmology is the base for what Baroque art represents and responds to: our insignificance in space, our status as intellectual and emotional specks of dust, and our attempts to comprehend such status.

“Perhaps it is not a coincidence that the formulation of the Big Bang is due, like many of the theories that gave rise to the Baroque, to a dignitary of the Company of Jesus: the Belgian Father Lemaître,” is another passage of Sarduy that I find particularly intriguing. If the transition from the Baroque as most understand it, placed in the midst of the last millennium, toward what Sarduy calls here and in other works the Neobaroque, which he tends to see in the words of Cuban writers, is as smooth as the pages of Baroque and Other Writings imply, this remark symbolizes a bridge between Europe and the Americas, reaffirming the Latin character of Latin America as an ineludible source of its cultural products. Nowadays, when myriad academic institutions promote a decolonial view of Latin American identity and expression, when conservative thinkers and politicians insist on the radical difference between Latin America and the Western world, Sarduy’s book, as the Baroque he describes, today certainly “subverts the supposedly normal order of things.”

Of course, a review of this book would be incomplete without pointing out the labor of Alex Verdolini, who curated and translated its pages with Iván Hofman’s assistance. “Any attempt to translate Lezama Lima, regardless of the results, should secure a place in literary heaven for the daredevil philologist,” said Néstor Díaz de Villegas about James Irby and Jorge Brioso’s versions in English of Lezama’s writings; we could say the same of Verdolini’s labor. But there’s more to applaud: not only have they taken the challenge of curating disgregate digressions of the author of De donde son las cantantes into a coherent tractatus, but some of the pieces in Baroque and Other Writings were written originally in French. The deliberate choice to include his brief text on the Fractal Baroque, a concept that finds its origins in Mandelbrot’s mathematical research, which is explored, but not touched upon in a detailed manner, invites other scholars to continue building on the ideas Sarduy has traced, for art, as he very well sentences in the end, “cannot be endless.”

Anyone disillusioned with the current lenses and strategies at producing knowledge by academia, infatuated by boundless, lyrical prose, and simply interested in the developments of science and art as two sides of the same coin from the cradles of Greek civilization to the chaos of today’s globalized economy, will find inspiration in the canvas that Verdolini has set for Sarduy’s ever-pertinent words—as the frame of a painting worth contemplating as both an object of study and a creative muse.