Editor’s Note: This is one of the three winning book reviews of LALT’s first-ever book review contest, held in 2023. We are happy to share the winning reviews in this issue of the magazine.

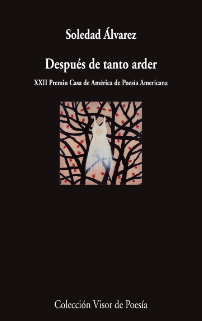

Spain: Editorial Visor. 2022. 56 pages.

On October 4, 2022, it was announced that Dominican writer Soledad Álvarez had won the twenty-second Premio Casa de América de Poesía Americana for her book Después de tanto arder. The prize’s judging panel agreed that Álvarez is “capable of using intimacy as a space of her own, from which to observe our world beset by wars and pandemics and reflect on feminism, family, or the servitude implicit in relationships” (Casamérica, 2022). Indeed, unlike her two previous poetry collections, Las estaciones íntimas (2006) and Autobiografía en el agua (2015), in which she offered glimpses of a suggestive, gritty eroticism, Después de tanto arder leans into a more elegiac style, almost entirely lacking in the rhetorical flourishes of her previous works, tending more towards introspection and recollection of happier times now long gone. In this sense, it is more closely related to her first book of poems, Vuelo posible (1994), in which the poetic speaker tackles the predicaments of her identity and its positioning in the world.

On October 4, 2022, it was announced that Dominican writer Soledad Álvarez had won the twenty-second Premio Casa de América de Poesía Americana for her book Después de tanto arder. The prize’s judging panel agreed that Álvarez is “capable of using intimacy as a space of her own, from which to observe our world beset by wars and pandemics and reflect on feminism, family, or the servitude implicit in relationships” (Casamérica, 2022). Indeed, unlike her two previous poetry collections, Las estaciones íntimas (2006) and Autobiografía en el agua (2015), in which she offered glimpses of a suggestive, gritty eroticism, Después de tanto arder leans into a more elegiac style, almost entirely lacking in the rhetorical flourishes of her previous works, tending more towards introspection and recollection of happier times now long gone. In this sense, it is more closely related to her first book of poems, Vuelo posible (1994), in which the poetic speaker tackles the predicaments of her identity and its positioning in the world.

This new collection from Soledad Álvarez consists of twenty-five poems divided into three blocks: “Oficio de casada,” “Bares y boleros,” and “Tiempo oscuro.” Like all her poetry books, Después de tanto arder is self-referential, meaning it acts as a record of the vicissitudes of a poetic speaker imbued not only with discords and disappointments, but also with an unsolvable state of melancholy. “Oficio de casada,” for example, centers on the dichotomy between the young lady in love of the past and the married woman of the present, and on how the weight of monotony and heartache capsizes any romantic idea of marriage: “the married woman does the dishes / and in the soapy water / in the suds of exhaustion / the young lady in love she once was / returns from oblivion to the start of her path.” She reminds us a little of the postures on the same matter put forth in Tolstoy’s Kreutzer Sonata (2003), in which an irreverent, aroused Pozdnyshev rails against traditional formulas of marital union, assuring that, despite any attempt, they are not sustainable over time. But Pozdnyshev does not go after boredom or disillusionment in particular (as our poet does); he focuses instead on the conflict between his own moral and philosophical ideology and the social conventions of his age. Álvarez does not seem to condemn the tradition of marriage, but does recognize (always resignedly) its fragile and artificial foundations, extending her pessimism to all areas of shared life.

In “Bares y boleros,” the poet sinks further into the memory of lost loves and nighttime adventures. At this point, the poetic speaker reveals her bohemian nature and somehow justifies her failure at marriage. The poet has left her passions halfway fulfilled: she treasures past trips and parties in the shadows; she holds tight to the touches of intense, fleeting lovers; her irrepressible desire to hit rock bottom is always just about to boil over. Not only do these elements corrode her; she defends and accepts them at face value, like someone being pulled along by the whims of alcoholism: “life is not enough without short-lived joy / nor is the bar without sorrow’s eternal return.” Such romanticism shows similarities to more recent poetry collections like La ronda de la vida (2023) by Uruguayan poet Cristina Peri Rossi. In this book, also with the trappings of autobiography, Peri Rossi attributes a component of self-destruction to the habit of letting one’s mind wander the nooks and crannies of long-lost youth: “Bubbles of pain / burst in my heart / and spill their burning bile / their bloody poison […] remains of lost loves, broken hopes, failed friendships…” But we can make out a glimmer of listlessness in the Uruguayan poet, who inspects her intimacies from the twilight of a small, commonplace life, far from any tumult and “free forever / from the opprobrious cult / of timeliness.” In this block, Álvarez does quite the opposite: her lost loves and unclosed tabs remain like open wounds in the lyrics of some bolero, unfading in the clamor of clandestinity.

Soledad Álvarez sets an important precedent for her artistic trajectory and presents an offering worthy of attention in the field of contemporary Dominican literature.

In “Tiempo oscuro,” on the other hand, Soledad Álvarez casts a panoramic gaze at her context, taking some distance from her personal dramas. While some of these poems allude to the other blocks, this space’s social calling stands out above all. Álvarez’s level of involvement and spirit of protest is not that of, for example, Gioconda Belli and her valiant poems against the governing regime of her native Nicaragua (her activism has led to exile and persecution). Rather, here we find a call to reflect on global matters, such as the grievances of irregular migration, the recent COVID-19 pandemic, and the military conflict between Russia and Ukraine. The poetic speaker, viewed from up close, suffers the onslaught of these phenomena, but prefers not to meddle. Soledad Álvarez, from her respective distance, leans instead towards optimism and wagers on literature: “I seek words images flourishes / that might let me escape the horror of the slaughter… until the end of the dark time of war / until we can go out and write / the gleaming poem of the love that saves.” Ultimately, the poet casts off her individuality to intermingle with victims and their afflictions.

All in all, Después de tanto arder, a book made up of irregular verses, represents a turning point in the poetry of Soledad Álvarez. This effort could be judged for falling into simple language. On this subject, Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges once said the work bestows upon the author the style he deserves. The same author claimed, furthermore, that it is proper for any young writer to adopt a baroque style in order to cover up his shyness or ignorance of literature, and that eventually, as he reads and gains experience, he will come to prefer simpler, plainer solutions. Perhaps this is why we notice a significant stylistic transition in Borges in Los conjurados (1985), his last book of poems, a compendium of intimate vignettes and well known characters, written in an understated key (especially in comparison to his debut, 1923’s Fervor de Buenos Aires, a portrait of his native city undermined by adjectives and intricate figures of speech). It seems Álvarez has come to the same understanding, and in this latest offering has stripped her verse down to the point that it flirts with the anecdotal. Having left behind the obscure language of previous books and landed on a confident, clear, and persuasive poetics, here Soledad Álvarez sets an important precedent for her artistic trajectory and presents an offering worthy of attention in the field of contemporary Dominican literature. In the end, the poet has given up the search for the sublime, and has chosen instead to retrieve and give new life to what lies among the embers.

Translated by Arthur Malcolm Dixon