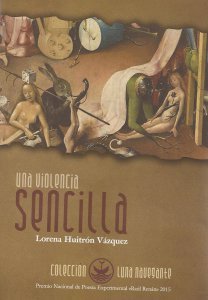

Una violencia sencilla. Lorena Huitrón Vázquez. Veracruz: Instituto Literario de Veracruz, Secretaria de Cultura y las Artes de Yucatán, Secretaría de Cultura de Veracruz. 2016. 72 pages.

To consider the wound and the scar is to appeal to words that name something broken in order to later sew up the discourse of violence and pain, such that later, perhaps, reconstruction will come. Una violencia sencilla [A simple violence] by Lorena Huitrón Vásquez, winner of the 2015 Raúl Renán National Prize for Experimental Poetry, is a reflection that explores the different places of violence imposed upon the body. In the epilogue, the author tells us of the book’s genesis:

To consider the wound and the scar is to appeal to words that name something broken in order to later sew up the discourse of violence and pain, such that later, perhaps, reconstruction will come. Una violencia sencilla [A simple violence] by Lorena Huitrón Vásquez, winner of the 2015 Raúl Renán National Prize for Experimental Poetry, is a reflection that explores the different places of violence imposed upon the body. In the epilogue, the author tells us of the book’s genesis:

“Una violencia sencilla emerged from a dialogue with a black man in the festival of San Mateo, celebrated in Naolinco, Veracruz… It was also a dialogue with his scars and those of others, other cases, other places. I found it very useful to consult several sources, among them El cuerpo herido [The wounded body] by Cristóbal Pera, Historia cultural del dolor [Cultural history of pain] by Javier Moscoso, and Anthropology of Pain by David Le Breton, along with dictionaries of surgery, books on scars, and medical articles. I mention clinical cases of loved ones and of others.”

The author has given the reader the routes down which the book travels, she has established the coordinates and the dialogues that it sustains with different sources. Nevertheless, seeing it this way, the reader could feel comfortable since, in the epilogue, the book’s explanation would be all wrapped up. Luckily this is not the case, since the epilogue neither summarizes nor synthesizes the content of Una violencia sencilla. It’s exegesis goes much further, the paths down which it travels are multiple because a good book is the sum of its parts, it’s the exact machinery of the strategies the author follows. It’s intelligence placed in the correct words.

I open the book and its first text surprises me, something shakes me up, and I think it’s all alright because that’s how it should be: the abandonment of the predictable. The poem tells us an anecdote through colloquial, flat language, without metaphors or literary tropes. We find ourselves before a simple narration that sets aside rhetorical grandiloquence:

En la primaria nos pidieron hacer una muñeca de trapo

Para aprender las partes del cuerpo.

Fue nuestro acercamiento a la cirugía.

Rellené a la mía de arroz,

La vestí a cuadros con su cabello de estambre café.

Mi madre le pintó unos labios pequeños,

Trazó una v invertida de nariz respingadita,

Ojos almendrados y pestañas largas.

Fui cirujana al coserla con hilo rojo,

Mis puntadas fueron discontinuas,

La aguja era muy gruesa,

Sin punta para no pincharme y llorar.

La presenté al día siguiente,

Hablé poco, volví al pupitre,

La recosté mientras el resto de mis compañeras

Presentaban a sus pacientes.

[In grade school they told us to make a rag doll

To learn the parts of the body.

It was our approach to surgery.

I filled mine with rice,

I dressed her in checkers with her hair of brown wool.

My mother painted some little lips on her,

She drew an inverted V, a pointy nose,

Almond-shaped eyes and long eyelashes.

I was a surgeon when I sewed her up with red thread,

My stitches didn’t line up,

The needle was very thick,

With no point so I wouldn’t poke myself and cry.

I presented her in the next day,

I didn’t say much, I went back to my desk,

I laid her down while the rest of my classmates

Presented their patients.]

The text is dominated by a sense of naivety; the poetic voice narrates a memory that could, at the start, seem innocent. Later the author introduces a quote that changes the tone because something interrupts, the voice no longer refers back to childhood, it does something else:

En el siglo XXI a una mujer le hicieron una mastectomía sin anestesia, se mostró hierática durante la cirugía y al terminar pidió disculpas, se vistió, lloró. De esto nada sabíamos, mucho menos que esa mujer se llamaba Alie.

Así debimos llamar a nuestra muñecas.

[In the 21st century they gave a woman a mastectomy without anaesthesia, she remained hieratic during the surgery and when they were done she apologized, got dressed, cried. We know nothing about it, much less that that woman was named Alie.

That’s what we should have called our dolls.]

I cite the entire poem because, in some way, it defines the path the book will follow; Lorena Huitrón succeeds in sewing together the poems with quotes from different sources (which she points out in the epilogue), the communicating vessels that are established between some texts and the diverse sources she consults, which are highly revelatory. In this sense, a good part of contemporary Mexican poetry, for the past few decades, left behind stable discourses. Its themes no longer deal only with metaphysics or the transcendental; it is written based on strategies and dialogues with diverse disciplines, sources that become evident through resources like recycling, copying, recontextualization, and inter- and trans-textual conversations—techniques that presuppose a dynamic, collective relation between the author and the language in constant use. In the case of Una violencia sencilla, we find, to a greater or lesser degree, some of these resources applied in an accurate, intelligent fashion. Lorena takes the body and its scars as her leitmotiv; around it she establishes a reflection that moves in the space of the poetic and the narrative: “It doesn’t matter how you cut or poke yourself, you establish complicity with the wound that’s about to emerge. The world is outlined by uncomfortable fibrosities.” A violence applied to the body, but focused primarily (but not exclusively), in this book, on the woman’s body. We should remember that, in the first poem, the author uses the simile of the doll.

I think of the book’s title, and I must confess that when Lorena told me about it, something in me became moved, pensive, perhaps because the union of the two concepts that make it up refer to antithetical aspects: Una violencia sencilla. A simple violence. But violence is never simple. Then came the questions: How does Lorena Huitrón write about violence? Through which resources? With which tools? What stories does she tell? Earlier I said that the way in which the poems converse with other books, be they historical, medical, or scientific, hits the mark. Yet the particular way in which the author addresses her themes is, without a doubt, the book’s strongest point. I dare to make this statement because it is in this realm where we experience a voice that cannot be confused with other voices of Mexican poetry. She has a particular style, a way of writing that shows itself to be solid.

Before moving on, another question presents itself: Could there be a superficial aestheticization of violence in any of its forms? It’s worthwhile to note that this question persisted longer than the others, as it relates to my particular personal interest in the subject of the violence that currently takes place in this country. I’m powerfully interested in poetic writings that address these topics; needless to say, there are countless well written and badly written books on the subject, but we must also say that many resort to the use of trite and sensationalist resources.

I try to be objective in this regard, to approach the book with the caution it needs, but as I mentioned before, from the first page of Una violencia sencilla I felt that it was somehow different. It’s well known that poetry doesn’t care about the what but the how; in other words, it doesn’t matter what you’re writing about but how you’re writing. I’m talking about the strategies and resources that the author employs to write about violence, the body, and sickness. I’m talking about the very language of Lorena Huitrón, her stance before writing.

Another resource the author uses, which I see as especially relevant because it’s uncommon in Mexican poetry, is humor, irony, and satire. We should recall that our tradition has privileged a grave, solemn tone. Nonetheless, Lorena leaves this trend behind, which transforms her into one of the few women writers to incorporate humor into her texts. She does so in a fulfilled, effective way: “In the operating room they give you anti-stress pills while your eye drowns in eye drops and radiation. It’s as if they stuck a chain of Christmas lights down you and the plug dropped to the pit of your stomach to let its sparkles pass through your whole body.”

In closing, I’d like to add some thoughts on the book in the context of current Mexican poetry: How does Una violencia sencilla enter into dialogue with other recent books? There must exist some mission, something gained, something that adds up. Lorena’s book points, from the thematic realm, to a concern that is present in much recent writing: violence. It does this in a very particular way, with its own voice. It is also inscribed in the poetics that abandoned affected and grandiloquent discourses; its language strives for clarity, or, as Gabriel Zaid would have said: for “difficult simplicity.” There is clear and evident formal work in Una violencia sencilla, a dialogue with other disciplines and readings incorporated into the poetic text. There is a way of writing that, as I stated, is different from any other. While the book fits comfortably into the curve of recent Mexican poetry, I like to think its individuality is what makes it moving and intelligent; I could use many adjectives to describe it, and I might not hit upon the best one, but every reader will do so for herself. I know with certainty that Lorena Huitrón was well deserving of the Renán National Prize for Experimental Poetry because her writing is, in my opinion, one of the most solid and outstanding bodies of work of our poetry. I applaud the prize, and I applaud the publication of Una violencia sencilla.

Eva Castañeda B.