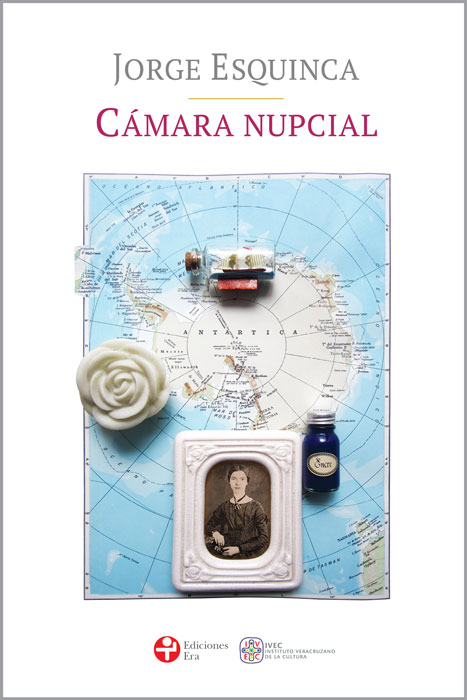

Cámara nupcial. Jorge Esquinca. Mexico City: Ediciones Era. 2015. 139 pages.

Cámara nupcial. Jorge Esquinca. Mexico City: Ediciones Era. 2015. 139 pages.

The Butterfly in the Snow

Del otro lado de la noche

la espera su nombre

su subrepticio anhelo de vivir

Alejandra Pizarnik. La última inocencia (1956)

Her name, her surreptitious desire to live

await her

from the other side of the night.

Alejandra Pizarnik. The last innocence (1956)

Emily Dickinson belongs to a strange family of writers who wield an irresistible attraction. The extreme brevity of her poems speaks of a concentrated soul, in tension, given to an intimate and nontransferable listening experience. Her works—the more than fifteen hundred poems that she wrote—are a question mark that, rather than be answered expect (hope/yearn) to be understood. This is the very attitude of Jorge Esquinca’s Cámara nupcial [Bridal chamber] (Era, 2015), which initiates a passionate dialogue with the leading figure of North American poetry. After making a pilgrimage to Amherst, Dickinson’s hometown, Esquinca gives us a book that continues and extends the evolution of his writing that began with Descripción de un Brillo Azul Cobalto [Description of a Cobalt Blue Brightness], an evolution very much born from the heart, free of the implication of ceasing to listen to the mind.

Between the book’s first image, the photo of Emily Dickinson’s dress, and the reproduction of one of her manuscripts at the end—with the constant and delicate presence of the snow in the background—the verbal adventure by Jorge Esquinca in Cámara nupcial does not disregard structure. Thus, the eight sections that make it up are eight paths traveled differently, but all directed toward the same destination: “Emily’s heart.”

The first part, “La maquinaria del glacier” [The glacier’s machinery], is a long poem that possesses constant motifs throughout the book, which makes one think that this poem was perhaps written when the book had already revealed its vision to the author: “Y voy dejando rastros, zarpas del que avanza / por ti, hacia ti, cazándote” [And I go leaving tracks, claws of he who comes for you, towards you, hunting you]. The second part, “Epistolario” [Letters] is a very brief dialogue about two letters in which, for the only time in the entire book, we hear fully Emily Dickinson’s voice; the third section, “Tratamiento del espacio fotográfico” [Treatment of photographic space], the author reveals to us Dickinson’s figure, as if it were a prism by which we are able to see her head-on, seated in the exact moment in which she is to be photographed at the age of sixteen. However, there may have been an erroneous detail here. The photo of Emily Dickinson “with a crimson ribbon around her neck,” which appears on the cover of Esquinca’s book, was not taken by Louis Jacques Daguerre, as suggested in this section: “Emily llega a la puerta da un aletazo suena la campanilla/avanza a donde monsieur Daguerre la espera” [Emily arrives at the door flutters her wings the bell wings / she advances to where monsieur Daguerre awaits her] and later: “Míreme ahora qué otra cosa soy sino el espacio abierto la novia de nadie la espiral del miedo monsieur Daguerre” [Look at me right now what more I am if not the open space the girlfriend of no one the spiral of fear monsieur Daguerre]. At the end of this section, we read a monologue that we could assume is spoken by the same Jacques Daguerre because of the surname quoted before: “Le pido que sostenga unas flores (…) Le pido que apoye su brazo derecho sobre la mesa. Que se mantenga erguida (…) Ahora no se mueve No sonríe” [I ask her to hold some flowers (…) I ask her to rest her right arm on the table. Stand straight (…) She doesn’t move now doesn’t smile]. This photo, taken in 1846, was not photographed by Daguerre but by one William C. North, whom by the way Jorge does not cite in any part of the book.

Note: (image): Daguerrotype of Emily Dickinson by William C. North (1846-1847).

There are two other things that I would like to point out from this section. The first is the inclusion of a translation—without a doubt much better than others (the one by Sra. Margarita Ardanaz Morán, for example)—from the poem “On the Marriage of a Virgin” by Dylan Thomas, done by Esquinca himself; the second is that the poem “Del otro lado de la noche la espera su nombre” [Her name awaits her from the other side of the night] is “un collage elaborado con dos versos de Alejandra Pizarnik” [an intricate collage of two verses by Alejandra Pizarnik]. This poem is also and above all a very brief alchemic manual for grasping that Matter (Dickinson) that piensa en la eternidad [thinks about eternity]. Pizarnik’s poem dedicated to Emily (from which Jorge Esquinca departs to write his), published in his 1956 book, La última inocencia [The last innocence], appears to the side, in the edition of his complete poetry, prepared by Ana Becciu and published by Lumen, of one of his most intense and cryptic poems he could have written:

alejandra alejandra

debajo estoy yo

alejandra

alejandra alejandra

I’m down below

alejandra

Enigmatic, brief, intense, like Dickinson’s, her spiritual sister.

The fourth part, “Libro de adivinanzas” [Book of riddles] is, to my liking, one of the best versions by Jorge Esquinca: short texts written in free prose, distended and playful, which refer to various poems, with regard to tone, from Teoria del campo unificado [Unified field theory]; “Invernadero” [Greenhouse] and “Gabinete de curiosidades” [Cabinet of curiosities] are the fifth and sixth parts respectively.

The cabinet poses, shall we say, an extraliterary relation with the same book: the cover is a collage made by Esquinca himself. On the upper part we see a small bottle that contains a tiny ship and in the manner of water, “…la arena/de un mar tan azul que hiere” […the sand/of a sea so blue that it wounds]. In fact, this connection is more organic and personal, it runs through and envelopes the entire book: the journey to Amherst, the photo also taken by Esquinca from his visit to the Emily Dickinson Museum, the cover artwork, Thomas’s version of the poem, and the partial reproduction of a fragmented manuscript by the poet. Finally, Cámara nupcial does not hide Jorge Esquinca’s other passion: Italian pictorial art, which in this case functions as a window through which one can look indirectly at Emily Dickinson: “…una tarde/en los Uffizi noté cuán parecida/eres a Flora en aquella pintura (…) no en cuerpo tal vez, sino en ánima /y, como ella, guardas bien tu secreto” [… One afternoon/in the Uffizi I noticed how similar/you are to Flora in that painting (…) not in the body perhaps, rather in spirit/and, like her, you keep your secret well].

The seventh part, “Viaje al centro de la nieve” [Trip to the center of the snow], is another long poem that describes the trip the poet made from Manhattan to Amherst. This text is perhaps the most intense moment of the book, for the concentrated expressive force that runs through it from beginning to end—despite some fissures: a distant echo heard at the beginning but shaken off later—by the rapid concretion of the images and also—why not—by the touches of bitter humor that run through it:

No hay un alma

entro para protegerme

de la nieve

¿es esto Amherst

es aquí finalmente he llegado?

Tras el mostrador, Catulo

asiente con un gesto

al tiempo que sirve un vaso

de mezcal

“Tenga, tómese

esto para el frío. Luego

siga calle abajo, encontrará

la casa de ladrillo”,

añade

“si la nieve le da permiso”

Suelta una carcajada

Dejo un par de sestercios

en el mostrador

“aquí no vale su dinero”

me dice al tiempo que recoge

veloz las monedas.

[There is no soul

I enter to protect myself

From the snow

is this Amherst

where I have finally arrived?

Behind the counter, Catullus

gestures in agreement

at the same time he serves a glass

of mezcal

“Here, drink this

it’s for the cold. Later

go down the Street, you’ll find

a brick house,”

he adds,

“if the snow lets your”

He lets out a guffaw

I leave a couple of sesterces

on the counter

“your money’s no good here”

he says at the same time he picks up

the coins quickly.]

“La vía negative” [The negative way] is the last part of the book, which rather than a denial, is a desperate affirmation to pierce that “roca en el centro del paisaje” [rock in the center of the landscape]. To achieve this, Jorge Esquinca had to be others: one who sets out on a pilgrimage to Amherst; the recipient of a letter that the poetess sends one Sunday; North who photographs her in 1846; one who poses to us her enigma by means of riddles; a raven that flutters and shouts at the family house in Amherst unnoticed; one of the people who carry Emily’s coffin. In short, one who clings to her “como hace el leopardo/sobre el lomo de la gacela” [as the leopard does/on the gazelle’s back].

“¿Debemos buscar con insistencia/la imagen de Miss Dickinson?” [Should we look insistently for/the image of Miss Dickinson?], wonders the Second Witness in Una forma escondida tras la puerta [A hidden form behind the door], a book that Francisco Hernández dedicated to the same poet. With regard to structure and conception, Hernández’ book is less ambitious than Esquinca’s, but no less enlightening and free (so free in spirit), like all of his poetry. In Una forma escondida tras la puerta it is two witnesses who uniquely speak to us about Dickinson while they spy on her movements, aside from her sister Lavinia (of whom the town’s seamstress took measurements to make the dresses that were for the timid Emily) who appears at the end to tell us that “la vida eterna de los poetas/tiene también los días contados” [the eternal life of poets/also have their days numbered]. Esquinca’s book, by contrast, displays ways of expression and traces various paths to reach that “flor fantasma” [ghost flower], in addition to incorporating experiences and discourses relative to poetry.

The Gardens of Emily Dickinson is a book Francisco Hernández presented to Esquinca, who now gives us this Cámara nupcial, where I find a beautiful “mariposa vibrátil” [fluttering butterfly]—an image of which I like to think the enigmatic figure who was and continues to be Emily Dickinson—has revealed itself to Jorge Esquinca to land in his heart that awaited it.

Audomaro Hidalgo

Translated from the Spanish by Rachel L. Bornstein