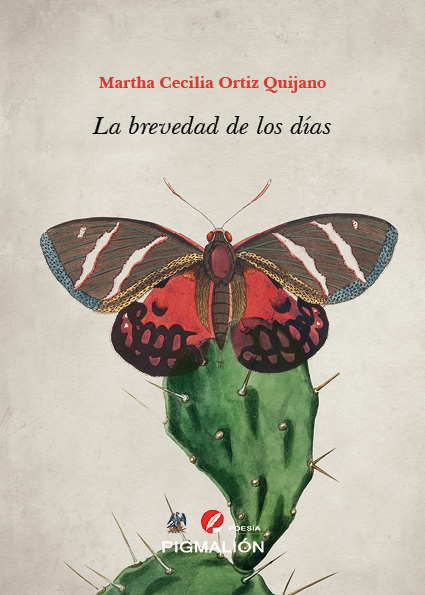

Spain: Pigmalión, 2024. 96 pages.

A country hemorrhages words. Poetry doesn’t hide the wound; it opens it to point out its shadows, its curves, its human accidents. Death, more than life, sliced through in a book where shouting struggles against silence. A country in the midst of a bleeding, excruciating poem, splattered with anguish and grief, its wounds an almanac of its losses.

A country hemorrhages words. Poetry doesn’t hide the wound; it opens it to point out its shadows, its curves, its human accidents. Death, more than life, sliced through in a book where shouting struggles against silence. A country in the midst of a bleeding, excruciating poem, splattered with anguish and grief, its wounds an almanac of its losses.

How short are the days that end in anguish, in the cardiac arrest of the prisoner condemned to execution, knocked down, hammered away at by death’s force. Death is a living character in a shifting stare. In La brevedad de los días, replete with the history of a beleaguered land, poetry can’t be the lyric verse of other eras. Here is the tearing away from other generations embroiled in verse that Colombian poet Martha Cecilia Ortiz Quijano spills out as if they were conceived together. Martha Cecilia is also the author of the poetry collection Desde la otra orilla (2020) and curated the anthology Luz al vórtice de las palabras: cartografía poética de mujeres colombianas (2022).

La brevedad de los días spans five sections. Five sections that gather together a stabbing, acute reality, so visible to the world’s eyes that it’s presented as a postcard of desolation, while the power of violence has made Colombia a sort of stitched-up map. The words that are surrendered to its pages warn against pain, the most violent images of the factions that have transformed this beautiful country of great Latin American thinkers and writers.

Thus, “El estallido de los gorriones,” “Álbum familiar,” “Los destellos del relámpago,” “A los otros,” and “Las mujeres que me habitan” form a tapestry in which this insistent figure—death—and the destiny of migrants, those with their burden of voices on the run and “the dead and the disappeared of the homeland,” those who are arbitrated by abuse, by the source of criminal policies, are the context of this poetic exhibit.

“Ortiz Quijano writes without ornamentation: her poetics is a blow, a grammatical scratch, a moving vortex of the laments of those for whom the death of their family members is always right before their eyes.”

Thus, poetry intervenes, takes charge of those who cannot speak, those who have lost the accent, the intonation, the substance of their laments.

This is a poetry of family, of those who are gathered together by memories but also by amnesia. Ortiz Quijano writes without ornamentation: Her poetics is a blow, a grammatical scratch, a moving vortex of the laments of those for whom the death of their family members is always right before their eyes, in their bodies, in the cadavers who speak through these lines, in the calculations that are carried out in an abandoned house, in a mother’s lost look, in a dead, missing, or banished brother, building into a supplication, a plea, an anguished poem spilling over into eternity.

From this marinade of emotions, Raúl Gómez Jattin and Alejandra Pizarnik emerge as the archetypes of this reality that occurs both in urban life and in the mountains, as it does in the soul of so many women who are Martha Cecilia Ortiz Quijano, a soul that exposes its content through prose that is rich in images, tension, and a landscape that is always that of a verbal society transformed into poetry.

Days are short, as death is eternal. Likewise, the poems that are combined here are brief, with a remarkable way of saying, praying, and singing openly, in front of all windows, all towns. This poetry will continue to speak as long as the blood of those who long to inhabit a kinder terrain continues to be shed.

Translated by Karen Martin