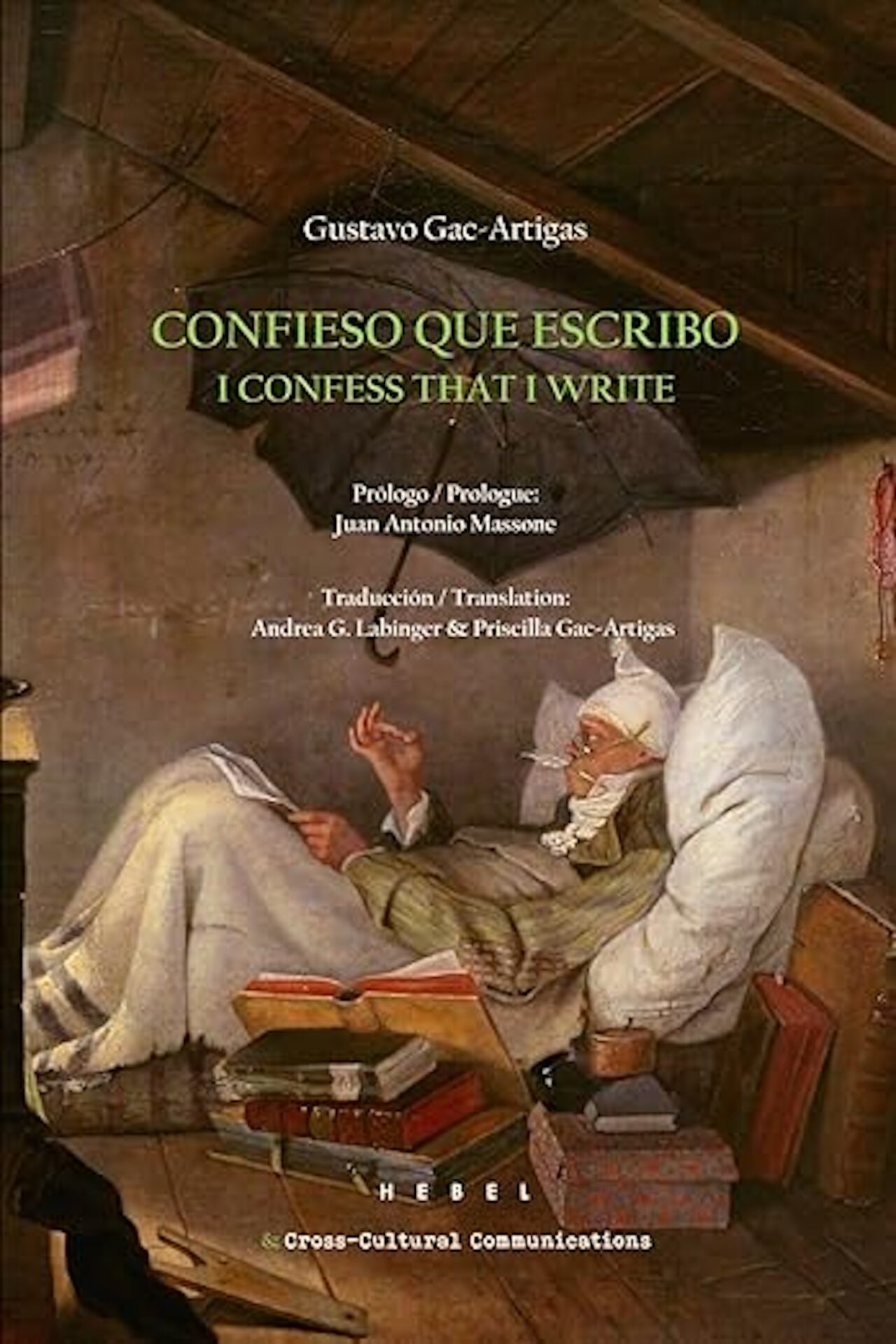

Chile, New York: Hebel Ediciones & Cross Cultural-Communications, 2024. 210 pages.

Confieso que escribo (I Confess That I Write) is a title that evokes that of Pablo Neruda’s memoirs, Confieso que he vivido (I Confess That I Have Lived). A homage, an entry into a proudly adopted lineage, the title makes clear the poetically autobiographical nature of Gustavo Gac-Artigas’s book, in the same way that his novel Y todos éramos actores, un siglo de luz y sombra, 2016 (And All of Us Were Actors, a Century of Light and Shadow, 2017) is an autobiography or fictional text centered on his trajectory as a director, actor, and founder of several different theatrical groups, both in Chile and in exile.

Confieso que escribo (I Confess That I Write) is a title that evokes that of Pablo Neruda’s memoirs, Confieso que he vivido (I Confess That I Have Lived). A homage, an entry into a proudly adopted lineage, the title makes clear the poetically autobiographical nature of Gustavo Gac-Artigas’s book, in the same way that his novel Y todos éramos actores, un siglo de luz y sombra, 2016 (And All of Us Were Actors, a Century of Light and Shadow, 2017) is an autobiography or fictional text centered on his trajectory as a director, actor, and founder of several different theatrical groups, both in Chile and in exile.

Chilean poetry has made a strong testimonial mark: suffice it to mention Gabriela Mistral, Pablo Neruda, Gonzalo Rojas, Violeta Parra, Jorge Teillier, Enrique Lihn, Óscar Hahn, José María Memet, and many other pertinent voices, each one an exponent of a poetics where tradition and innovation, experimentation and evidence, have been combined in distinct ways. Nonetheless, located in all of them is a reflection on the link between language and reality, in a historical context marked by violence and (self-)censorship.

Within this tradition, the poetry of Gustavo Gac-Artigas finds its personal outlet in an austere style, with pristine, eloquent clarity, and themes focused on the relationship between poetic subject and writing that defines and establishes his humanity in contact with others.

Designed in this way, the act of writing is an offering to the other, a reflection of the one who is writing, and who loses his name upon fusing with the recipients of the poetic communication. That is why “raison d’être” with which the collection of poems begins, confides to the wind the answer to the question “what purpose lies within my verses?”. Because the person who can really explain this is the other, invoked in the poem that acts as the book’s epigraph: “i write for you / without ever having met you // i write for you / to find myself // i write on the wind / with no return address”. Not for nought in “i ask you for forgiveness” does the poet address a broad and inclusive plural “you,” poetically apologizing for having “stolen” their lives, loves, sorrows, dreams, and thoughts, making use of a confessional apostrophe in order to express the idea that all the poetic material specified in these poems is a flagrant—joint—invasion of every sort of privacy. Poetry is nothing more than the appropriation of the other’s pain, which is one’s own, as long as the lyrical voice is an interdiscursive interpretation of a plural “I” whose scope is social and historical: the prisoner poet, the solitary man, the neglected woman, the betrayed childhood.

“A summa of its author’s poetics, I Confess That I Write offers us his love for words, his trust in the liberating power of the verb”

The choice of writing, and poetry in particular (cognitive act, enlightening vision of an object, language evading all rules) thus seems like an abdication—of a language muzzled by euphemism, of a clichéd view of the world, even of a desire to paint beauty with brilliant colors in dark times (as in “painter,” “prudish,” “i dreamed of you”)—followed by a choice of testimony. In “the writer toward the scaffold,” this seminal contradiction reprises the structuring leitmotiv of deseos / longings / j’aimerais tant (2020): “how i would like to sing to the stars / to the moon…”, now flung into the counterfactual dimension of dreams by the presence of reality: “but living in these tempestuous times / I can’t unstick my gaze from humankind.” The choice has consequences: “i picked up the pen / and my hand trembled / as once again i signed / my death sentence.”

A series of poems, discontinuous but present throughout the poetry collection, focuses on the word as a reflective theme. In this series, Gustavo Gac-Artigas gives shape to a poetics encoded in nature and uses of language: we think we possess a language when, in reality, it is the words that possess us, pierce us, speak to us, establish our humanity, but do what they want to do: “because they refuse to be tamed / and they scoff at spelling”; “because they’re fierce / like the wild horses of my land”; words that cherish and have an impact; inflict pain and, with it, vulnerability; that are “my jailers / and the keys to my freedom”; that do not require embellishments: “naked” and “unadorned” they are more beautiful and friendly; they are the masters of our thoughts: “she deflowered my thoughts.”

The choice of poetry as a form of life implies a conscious and responsible reassessment of words: making them your own, liberating them from prefabricated speech: “ever since childhood / i was given the word of others / shrouded.” And that, moreover, implies a radical change in the way of seeing the world, as it is well known that language, and especially certain discursive formations, constitute a filter capable of falsifying the gaze. That is why the poet, in “decisions,” demands of himself that he “change the way i observe my universe,” “erase my past” and, in “ode,” proposes that he sing out of necessity, give voice to those in pain, to the dispossessed, to those who conserve “the grandeur of soul in misfortune.”

Two poems synthesize the answer to the question “why write?”. The first is “intentions,” within which are intertwined three themes that traverse Gac-Artigas’s poetics: exile (“i write to return / to the country i should never have left”); love (“i write to be reborn in your arms”); and the other who suffers (“i write for my people / those I never knew / but whom i embraced from afar”).

The second poem is “definitions and hesitations,” an ars poetica in which the lyrical voice expounds on the historical dimension of his writing: “to write about the life we’ve lived / allows us to write about the future”; its social function: “to emerge from one’s individuality and join the throng / allows us to accept ourselves / to exist as part of humanity”; its potential to soar: “to dream allows us to liberate time / from its fetters / to escape the chains of utilitarianism / and to be uselessly necessary”; to flee from chapels and schools: “to write without coupling / allows us to transcend our preferences / to return to zero / the intangible / the solitary scribe”.

I Confess That I Write reiterates two characteristics which permeate all of Gac-Artigas’s poetry: first, the absence of capital letters and punctuation, an off-shoot of his decision to transgress the rules of “good manners” that domesticate language; and second, its bilingual presentation, in Spanish and English, the latter translated impeccably by Priscilla Gac-Artigas and Andrea G. Labinger (deseos / longings / j’aimerais tant was in three versions: Spanish, English, and French), not only a response to the fact that the author resides in a country whose official language is English, albeit with a growing Spanish-speaking population, but also to vindicate the translation of poetry, once considered “impossible,” but here defended as a work of art with the same high standing as what was previously considered “the sacred original.”

A summa of its author’s poetics, I Confess That I Write offers us his love for words, his trust in the liberating power of the verb, his generous decision to wield it as a key to change the world, his unconditional dedication to those who suffer, his passion for pursuing the luminous traces of truth in our tormented world.

Translated by Lilit Žekulin Thwaites