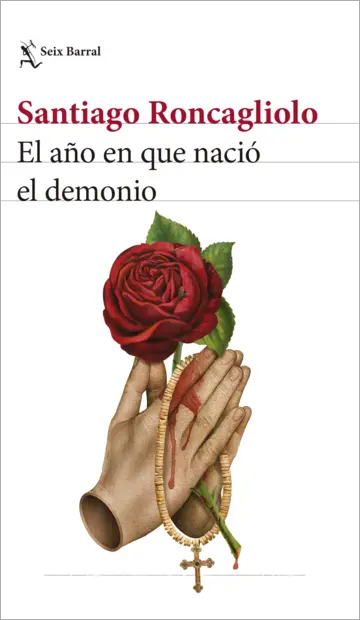

The dark and convoluted seventeenth century provides the setting for El año en que nació el demonio (Seix Barral, 2023), a new novel by Peruvian author Santiago Roncagliolo, winner of the 2006 Premio Alfaguara.

The novel invites us to inhabit a world where the boundaries between the sacred and the fantastic were blurred, in which indigenous myths were viewed as having “infected and deformed our systems of knowledge,” that saw the publication of religious missives and tracts while books deemed “harmful to the mind” were condemned, and in which the Church is corrupted from within by plotters working in the service of the Peruvian Viceroy of the day.

With this latest work, Roncagliolo traces the contours of a story where witches, nuns, and an Inquisition prosecutor named Alonso Morales seek to uncover the true provenance of a creature born in Ciudad de los Reyes in 1623. Running the gamut from saintliness to sorcery (the young woman Rosa, for instance, is rumoured to be able to converse with God and the Devil), this novel masterfully traces the hidden corners of political and religious thought in a period when outsized concepts of good and evil were cast as direct opposites.

Juan Camilo Rincón: You initially set out to write a novel about twenty-first-century witches, but the archival research process led you to the 1600s. Had you any prior knowledge of this period?

Santiago Roncagliolo: No, I was pretty clueless, and had no special interest in it. At the same time, there was a personal connection via my grandfather, to whom the novel is dedicated. He was a historian. People said he was a conservative historian, but that’s not entirely accurate. Conservatives want things to remain the way they are; my grandfather wanted a wholesale return to the eighteenth century, which seemed to him like a much more reasonable, more comprehensible and more civilized place than the country he had grown up in, which was pure chaos, a disaster no matter what period you were living in. Chaotic in a general sense. His feeling was that, back then, at least there had been order. I started studying his books, which in reality constituted the world he inhabited, a much more tolerable one than the world he existed in physically, and I started to see the world through his eyes. This was partly my motivation. He wasn’t a leftist exactly, and he saw the act of interpretation as a Marxist move. For him, history was just there, it was what had happened and there was no reason to repeat it. His books are full of details; he was like a demon in the archives and he found gold in the personal lives of the people of that time and in the theatre of the time; a whole chapter in the novel takes place in the theatre, which comes from a book of his, and from there I also began to encounter this universe in which everything was sent by God or else sent by the Devil, full of witches, saints, flagellations, heavens and hells. The more time I spent there, the more I became obsessed with this world, because of how it lies at the root of the one we live in now, but also because of its visual splendour and how fascinating it was to set a story there.

J.C.R.: Tell us a bit about the book Las hijas de los conquistadores, one of your sources.

S.R.: It’s a book by Luis Martín, who I believe was a Jesuit. That’s where I got a lot of my ideas for the portrayal of the convent, which is really a kind of liberated territory. Martín’s book has these wonderful details, like the letters sent by a bishop to Rome saying he has already told the nuns in his convent they cannot sleep in pairs, and so he’s bought them mattresses, but with their new mattresses they continued sleeping in pairs and they just don’t get it! In many of these convents, the women might be lesbians, or sexually active, or writers or singers, and they were freer than the women on the outside. Many convents were violently raided by the army to contain these nuns with their decadence and their scandals. But there are also the holier types like St. Rose who, in their own way, find a way to avoid being somebody’s wife; marrying God was one of the best escape routes.

J.C.R.: They also tell us a lot about the spirit of the age.

S.R.: The thing is that the nuns were the wives of God in an official sense, but the truly holy among them were also wives in the sense that they were in direct communication with Him, receiving instructions and performing miracles. At the same time, it was a way of life that was not so far off from witchcraft—after all, what’s the difference between talking to God and talking to the Devil? Or between casting a spell and working a miracle? However, these women also found a way to acquire power, admirers, and dedicated followers. When St. Rosa of Lima died, the crowds threw themselves on her corpse to tear off strips and keep them as relics: a fingernail, a tooth, or a hair. Another kind of path that could be followed. And then there was the rebellion; out of that there emerged characters like Mencia, Jerónima and Alonso’s own mother, who also found a way to live, to try to help her son… It’s more warped, but it is still a way of living and of trying to survive in that world.

J.C.R.: Have you always thought of Alonso Morales in the first person?

S.R.: For me, it was very important that he wasn’t a person who thinks like someone from the twenty-first century, that he wasn’t just some guy plonked down into a seventeenth century setting. I had to get inside his head for this project to work, for the reader to be able to follow his thoughts and from there to see the world he inhabited; otherwise, it was going to be very complicated to get into the story. He’s trying to figure out why the Devil has appeared, so to begin with he needed to have a lot of internal monologue going on inside his head. The archaic language is another crucial element here; it was the most difficult thing to reconstruct, but it helps you to get into the seventeenth-century mindset. The first version was formally accurate, but I realized it was also unreadable. In any case, the whole exercise was already fictitious by nature because, to begin with, he would never have written about his own life in a report. If I became overly concerned with verisimilitude, the story would be impossible to write, so I had to play with what I knew of the language to create one that would be convincing, but at the same time would be entertaining, and that readers wouldn’t have to struggle with on every page.

J.C.R.: Someone was saying this is a novel about bodies, and it made me think about how, during this period, the body was a vehicle for many things: sacrifice, public torture as a mode of instruction, the liberated bodies of the nuns, the immaterial body as a pathway to God…

S.R.: The Catholic church has a blatant hatred for the body; it regards the soul as that which brings you closer to God and the body and its appetites as doing the complete opposite of that. In fact, one of the things that struck me was how flagellation was viewed as a sign of virtue: you flagellate and punish yourself, hurting your body in order to be a good person. I remember one time I got hurt playing soccer and my grandmother told me: offer that suffering to the Lord. This idea has survived until very recently in Catholicism, the idea that your body is bad and therefore pain is good, because it punishes your body. Rosa is constantly destroying her body; she spends her whole life doing it, nailing spiked chastity belts to herself, sticking her hands in quicklime because her body could attract men, and was therefore wicked and impure. Many of today’s political struggles revolve around having ownership of your body. From abortion to transgender rights, most of today’s progressive causes are about defending the right to do whatever you want with your body, that it’s up to each person to decide. Nowadays, the novel’s witches would all be political activists. They are the ones leading the marches, rather than ascending the scaffold to be hanged. I guess that’s a kind of progress.

J.C.R.: What was your biggest challenge in writing this novel?

S.R.: The language, which I started working on in a very rigorous way before realising it wasn’t necessary to use seventeenth-century language; instead, I had to invent a language that sounded sufficiently like the seventeenth century, and that would allow Alonso to tell his own story while still retaining the register of an official report. The main difficulty was not that it was very complex language, but quite the opposite: it is very simple. It’s a very simple society where everything is binary: God is good, the Devil is bad and so there isn’t much room for nuance or grey areas, but you can’t sustain a novel with such two-dimensional ideas and characters. The characters had to be complex; they all have positive attributes as well as woeful ones, but it had to work within this language that, on the surface, is so basic and notarial. That was the hardest part.

J.C.R.: Which is your favourite character, or which was the hardest to construct, for example?

S.R.: The women were the hardest. Mencia, for example, who is terrible, overbearing and egotistical but is also a heroine; she has freed these women from the outside world, which is a much worse prison than the world of the convent. Jerónima is another, because I like this idea that she was real (she’s also taken from Luis Martín’s book). Women were very liberated inside the convent, but black women were still black; there was no equality of races or backgrounds. However, a dark-skinned woman could become a nun if she sang well because the choir was where the nuns’ voices rose up to God, and if those voices were beautiful, God would be more inclined to listen. Indeed, there was a Hieronymite nun who was dark-skinned and who was accepted as a nun because she sang. And then Rosa herself, whom I still find difficult to classify: is she psychotic, is she a witch, or is she a saint, or simply an ambitious woman who has found a path to obtaining power? I don’t think we will ever know, and that ambiguity fascinates me and makes me fall in love with her. Alonso is like my proxy in this world, he represents my own inability to understand these women or what it is that motivates them, maybe because you always want to think they are just one thing and in the end they are all things at the same time.

J.C.R.: And also the characters have many nuances; there aren’t any all-out good or all-out bad guys.

S.R.: That happens a lot in my books. Things get inverted and the detective ends up being almost indistinguishable from the monsters. And the monsters end up being not too different from the detective. I like the idea of genre fiction where there’s an investigation. It’s important that it be a personal investigation on the part of the protagonist; that they find out something about themselves and that it changes their life. That the detective not only solve an external mystery but that they undergo a change in the process; that neither detective nor reader can ever be the same afterwards. I think, in the end, we all see everything as being about ourselves. If we’re drawn to a protagonist, it’s because they embody things we carry within ourselves.

J.C.R.: What was the discovery that most surprised you while you were trawling the archives?

S.R.: On a historical level, everything I’ve just been talking about, but what constantly surprised me were the things that still haven’t changed to this day. Like the city in which the story takes place, which is this walled enclosure inhabited exclusively by white people, away from other races and socioeconomic classes. I mean, just look at this neighborhood we’re in right now, or my neighborhood in Lima, or Latin America as a whole, which is still full of these exclusive, gated settlements. The Inquisition-era ideas of women as inherently guilty and of public punishment are now at the heart of how social media operates, with its show trials and its merciless shaming of those who don’t play by the rules. I believe twenty years ago we were more modern than now; today we are getting closer and closer to the seventeenth century. Modern democracy (which we thought had triumphed as an idea, at least in the 1990s) was based on a very revolutionary principle that had never been applied before in history: the idea that if someone is different from you, they are not a bad person, but just another person with whom you agree to coexist. The financial crisis, then the pandemic, resource depletion, and then corruption… Many things have been causing people to doubt democracy’s viability as a system, but if there’s no democracy, we are left with what we had in the seventeenth century: the tribe. We’re the good guys, and everyone else is wrong and must be punished, canceled, silenced. Social media lets you gather a tribe together in five minutes flat, two hundred thousand people or whatever, and what’s more, they’ll make you feel good because you can post your thoughts and if those thoughts are witty, you can have ten thousand people giving you a “like” and making you feel like you’re on the right side of history. Suddenly you are the inquisitor: you’re the one who knows how people should be.

Translated by David Conlon