“What do you think literature boils down to? To writing from the belly rather than from the cheek. Most people write from the cheek. If the semi-illiterate criminal wrote a long letter ordinarily to his sweetheart, it would be what most letters of such people generally are. If the criminal wrote this letter last thing before his execution it would be literature.” V.S. Naipaul responds thusly to his father in a 1950 letter.

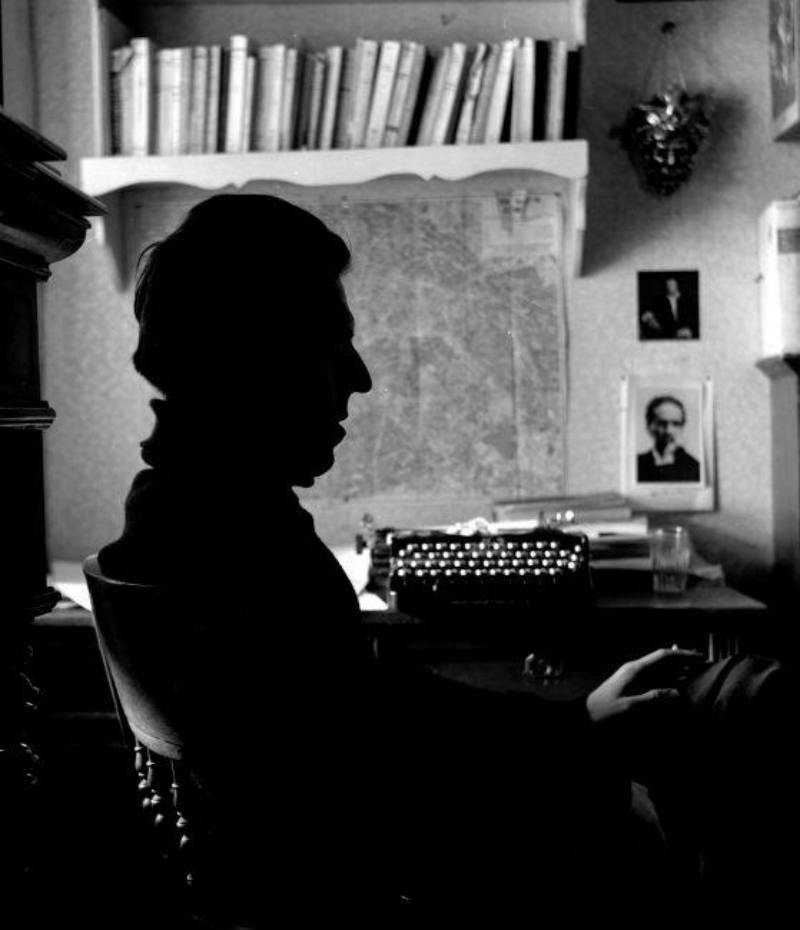

Julio Ramón Ribeyro was relentlessly pursued by illness throughout his life. He was once told he had six months to live. His photos, in black and white, show a slender, delicate man, in perpetual convalescence, who clings to life through the timid filter of a Lucky Strike cigarette.

He fought this battle against time, against death, all alone, with the little typewriter at his side as his only weapon. He wrote from the belly, compulsively, knowing he was getting worse, spanning almost every genre: short story collections, novels, theatre, articles, essays, letters, and diaries. Ribeyro wrote the way you make love, in that intimacy where you die and are reborn; I discovered him in my second year of secondary school. My parents had enrolled me in an exclusive boys’ school, ruled over by Italian priests. The school’s architecture was classical, with a few Neo-Renaissance touches and apparent influences from some Venetian palace. The ceilings were high and the columns were girthy and gray like elephant legs. Life in the school was hard: being the new kid meant having to fight at least a couple of classmates per month. The cliques and friendships were already in place, so at recess I limited myself to watching the older kids play soccer.

Sometime in those first few weeks, I was approached by Nieto, the Language Arts teacher. They said he was a weird, unruly guy. We students prayed every morning in the chapel before classes started, but he was an atheist, so he just stood there, under the doorframe of the main entrance, with his hands crossed behind his back and his legs slightly separated, until this liturgical activity reached its end. One day he came up to me on the soccer pitch and handed me a few mimeographed pages. The title was printed, “Los Gallinazos sin plumas, 1955,” on the front page; I remember devouring the story, carried away. When I returned to class, the teacher was talking about the chemical elements, but I couldn’t clear my head of Efraín and Enrique in the trash heaps, of Don Santos with his wooden leg, of Pascual the pig. The story, written in the fifties, spoke to me with still-living freshness about extreme poverty, marginality, and social exploitation. How was it possible that a grandfather, Don Santos, could feed his pig while denying food to his family? It was a painting that revealed, in just a few brushstrokes, the sad reality of my country.

Nieto, by accident, in the midst of his whirlwind of boring academic and administrative tasks, had introduced me to me my first friend at school. From that day on, at every recess, I would run to the library and seek out everything I could find about Julio Ramón Ribeyro. At the same time, the school teachers did their jobs: they religiously taught me mathematical equations, chemical formulas, historical names and dates to memorize, but the writer prepared me for life. With him I learned the subjects I really needed to know in order to meet adulthood head on: uncertainty, indetermination, conformism, shyness, inequality, deception, frustration, failure, hatred, unease, love, friendship, deceit, racism, alienation, violence, death, migration, and modern solitude.

***

In the spring of 2013, I go to Paris. The son of Julio Ramón Ribeyro is also named Julio Ribeyro, and to tell him apart from his father I call him Julito. We agree to meet up in a neighborhood near the Monnaie. I see him emerge from an avenue, wearing a casual jacket and a checkered shirt, walking unhurriedly with a newspaper tucked under his arm. I wave my hand and he responds with a greeting. He knows a bar where they play sixties music. There are some tables shaded by umbrellas on the sidewalk outside, but he prefers a table inside. The waitress comes by and I order a rum and Coke. He does the same. Once we’re alone, he asks me which of his father’s stories I like best. I think of it as a test, I ponder the question for a moment; then I give him three titles and explain why they hold such attraction for me. Julito, relaxed and polite, takes the initiative in the conversation:

“As time goes by I’ve started to forget the figure of my father, but I remember a few moments of my life with him: listening to soccer games on the radio, day trips to the beach, taking interminable flights from Paris to Lima. He didn’t much like flying because of his illness; it was hard for him to stay in certain positions for a long time. On Saturday morning we would go out to buy spaghetti to cook with pesto sauce, we would often go shopping at the bodegas in the Barrio Latino, he was a great cook.”

“Did he walk a lot?”

“Yes, he was a flâneur, he had a tremendous ability to wander around and lose himself in the streets. He didn’t like to take the bus. He always walked to UNESCO, where he worked for a long while. It took him twenty minutes, and he always adhered to that routine of coming and going, rain or shine. Luckily, Paris was built for the pedestrian, for the solitary man who dares to lose himself in the multitude.

The waitress appears with glasses of rum. “You’re just in time, we were dying of thirst,” Julito says. The bar is big, and at this hour there are just a few of us customers spread out in the main room. He drinks at his leisure, then takes out a pack of Lucky Strikes and offers me a cigarette. “I quit smoking,” I answer. We listen for a while to the heartrending voice of Janice Joplin, filtered through the speakers, and then he tries to reconstruct the image of his father.

“From a distance, I see him almost as a quixotic character, an idealist. He went through moments of hunger and pain, he held a lot of night shifts and physical jobs: he was a stocker in a market and he picked up old newspapers, and that work ended up taking a toll on his health. He set about writing as a romantic act. I think it’s difficult to write in a language that is not one’s own, and that’s why he didn’t use French as a literary language, although books by Maupassant and Flaubert were always sitting on his bedside table. He read the Peruvian press, he tried to keep up with Peruvianisms; every time a fellow Peruvian came to Paris, he would go looking for him just to listen to him talk. In my whole life, I only ever heard him use two Gallicisms, and he was embarrassed by that, by not being able to find their equivalents in Spanish. He wrote diaries religiously and constantly, and thanks to that he learned how to express a lot with very little: an idea, an emotion, in tiny fragments.

“Was he very shy?”

“I think he was shy, but his shyness went away with age. Perhaps his shyness was voluntary in his old age and real when he was young. He didn’t take long to understand the burden that comes with fame: the interviews, the obligations to his readers, the fact of people coming after you and invading your privacy. Public relations always bothered him, he wasn’t made for that. He didn’t like advertisement or adulation.

‘Watch out for writers who speak highly of their own work, who can explain it to you in abstract or analytical terms. Let the critics and the academics comment on it, that’s what they’re there for. What little time an artist has should be dedicated only to his art,’ he used to tell me. On the other hand, he was very sociable with his circle of friends. Alfredo Bryce, Luis Loayza, Vargas Llosa, and Julio Cortázar used to come by the house and read their work. Leopoldo Chiararse, Rodolfo Hinostroza, Emilio Westphalen, and several others I don’t recall. Whenever my father read a good manuscript, he got excited like a little boy, he didn’t care about the name on the cover.”

The noise of traffic comes in off the street, and then the sudden musical explosion of a group of North African immigrants; we hear laughter, there must be about six or seven guys: the singer is a black man with a neatly trimmed mustache and a white silk suit embroidered with green thread. Julito watches and sucks intensely on that useless paper cylinder stuffed with tobacco. He seems not to feel the effects of time, nor those of the glasses of rum we are slowly emptying. The waitress comes by and picks up the empties, with Mediterranean laziness and typical Parisian coquetry.

“Last year, I went to Máncora with my partner. I had shrimp for lunch on the beach and it gave me an instant allergic reaction, I started to swell up in hives. I had to go running to the hospital, I was having trouble breathing. When I get to the examination room, the doctor asks me my name, then he starts talking about my father and telling me he’s a devoted reader of his work. He says he wants to take a photo with me, he gets out a Polaroid camera, he puts his arm around me like we were old friends. My face is blushing bright red at this point, my lips look like Angelina Jolie’s, I’m a big purple monster without an ounce of air in my lungs. While he’s prescribing me some antihistamines he looks at the developed photo and says, ‘You look just like your father.’ Strange things like that happen to you when you’re Ribeyro’s son.”

He stamps out the butt of his cigarette in a glass ashtray. As the sunlight beats down on this slice of the city, the ashtray becomes a piece of pure, brilliant quartz, floating on our table, until a little cloud darkens it again.

“My father wore his sense of humor on his sleeve. I remember a joke he used to tell me: ‘Three men are shipwrecked on a desert island, a Chilean, a Bolivian, and a Peruvian. They find a magic lamp. When they rub the lamp, the genie appears and tells them he’ll grant them each one wish. The Chilean says, “I want to be with my family.” And the genie grants his wish. The Bolivian asks for the same thing. And finally the genie says to the Peruvian, “What is your wish, master?” Seeing he’s been left all alone, the Peruvian says, “I wish my friends, the Bolivian and the Chilean, would come back.”’” I laugh. But at this point, with six rums running through my veins, I don’t know what I’m laughing at. Julito raises his glass and swirls the ice cubes with his index finger. I take a swig of my drink, but he seems to just wet his lips; his glass hangs there for a few seconds, and then he makes the liquid disappear in a single sip, like a magic trick.

“Your father was a great letter writer, did he write to you?”

“No, because there was no need, we lived together. I only left his side when I went to study film in London and when he came back to Lima. I don’t know why he went back to Peru. My mother got used to France quickly, she worked a lot as an art dealer when my dad got sick, she had to be the source of support for the family. My father never integrated in France, he was still glued to a circle of Latin Americans, but many of them left Paris, others died, in the end he didn’t have many friends here. My mother used to travel throughout Europe, she had work meetings in different museums and galleries, which made my father’s sense of solitude grow. Maybe he went back to Lima because his homesickness won him over. He was like that: when he was in Madrid he missed Lima, when he was in Paris he missed Madrid, when he was in Germany or Belgium he missed Italy. Now that I think of it, there was one letter he wrote me—he never sent it because he passed away—where he talks about art. I think I’m a big perfectionist, and that makes me frustrated, it makes me censor myself. In the letter, he tells me that’s a mistake and he says I should make films. I didn’t understand at first. How can someone who’s dying talk to his son not about love, but rather about art, about some idea or other about aesthetics. But after that, analyzing that missive again, I’ve come to think my father hit the nail on the head: he wanted to give me an important piece of advice. Maybe that flaw wasn’t persistent in my character, but it was there, embedded into me. That obsession with perfection had tied my hands, it didn’t allow me to express my vision in a concrete project. One way or another, that letter he never sent ended up setting me free.”

My only brief encounter with el Flaco took place in 1993. Julio Ramón Ribeyro was in Lima presenting the second volume of his diaries, titled La tentación del fracaso [The temptation of failure]. That day, I failed to get his autograph, and he passed away a few months later. I tell Julito about it. He asks me if I have any of his father’s books on me. I look through my bookbag and hand him a copy of the diaries. A little uneasy, he looks at the book, spends a few seconds reading the back cover, opens it, and signs, “J. Ribeyro, hoping it was worth the wait.”

Translated by Arthur Dixon