Although the essential element of our lives is time, we generally pay little attention to the long-term perspectives that open up to us at every moment. We only start drawing connections between them—if our curiosity survives—when we have already made it a long way down the path. We have always known our time is limited, but, at a certain point, this starts to become a certainty: we cannot keep searching indefinitely. In literature, this search turns into an immeasurable abyss. This is one of the reasons why I believe in critical observation as part of the book world’s ecosystem: the need to discern, to not be deceived in the midst of this vastness—a vastness that, these days, is algorhythmically multiplied into a sort of unguided, directionless chaos.

With the boom of online publication came the measurement of performance per article. These “success” metrics showed that book reviews and critical essays enjoyed scant readership. Criticism once lived through a golden age, from when it witnessed the birth of romanticism to when it found its place in the depths of the turbulent twentieth century. At that time, an essay by Eliot, Ortega, Simone de Beauvoir, or Paz was a newsworthy event. Today, on the other hand, the dictatorship of opinion and speed reigns supreme: social media has replaced argument with affront, deep reading with the 140-character decree. Out-of-context quotes, our obsession with lists, booktubers and bookstagrammers, and the book clubs of actresses and singers have turned into a deceitful extension of sales-obsessed publishing PR. And this is not the only flank on which criticism finds itself threatened: it seems the fire is coming not only from without. A sector of the academy has decontextualized criticism to an extreme degree, pushing it to a place where representation is crucial, but quality is not; to a “presentism” that refuses to converse with the past and sometimes shuns it completely. The figure of the literary critic, which seems to be disappearing or fading into a thing of the nineteenth or twentieth century, is therefore unavoidably necessary, as are conversation, judgment, disagreement, and mutual understanding.

“What is a literary critic?” Christopher Domínguez Michael asked in his address upon being accepted into Mexico’s Colegio Nacional in 2017. This question leads to others, and his effort to answer each of them gives us an idea of the kind of critic he is.

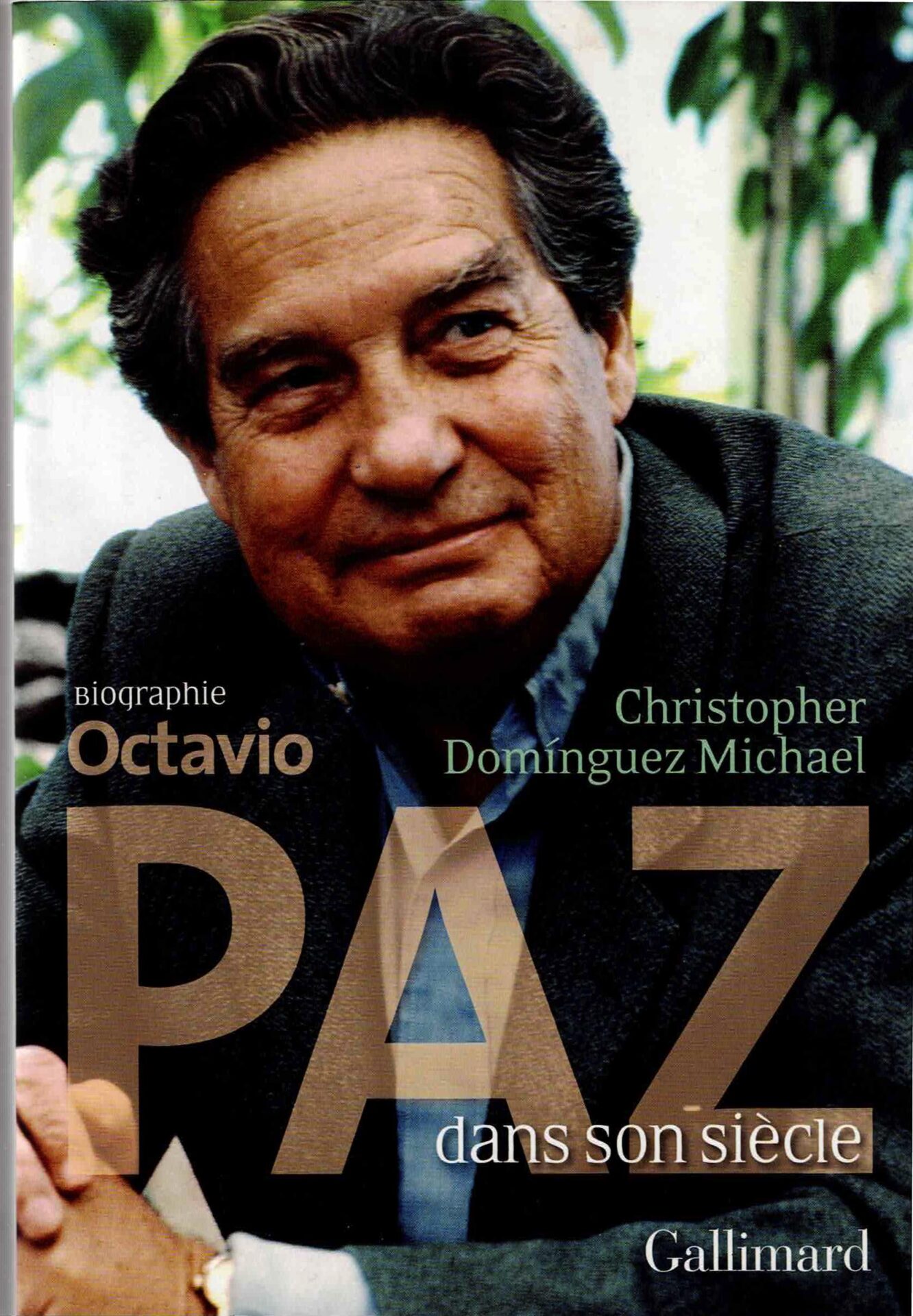

After leaving university, Domínguez Michael came up in the world of Mexican magazines and literary supplements created by Octavio Paz and Fernando Benítez. This world—one of financial modesty but intellectual richness—was his real school, where he confirmed that, for him, political, intellectual, literary, and artistic criticism—which Paz practiced as something akin to breathing—was an enthralling passion. He learned to distinguish between boldness and bravado; he learned that intellectual freedom is a matter not of caprice, but rather of judgment undergoing a constant exercise of doubt and risk. The critic must be brave without being reckless, and combative without turning his adversaries into personal enemies.

I do not believe it is by mere coincidence or editorial chance that the first text of Ateos, esnobs y otras ruinas (Ediciones UDP, 2020), where Christopher Domínguez Michael brings together his essays on twenty-first century letters, addresses the Islamic State’s capture of the ruins of Palmyra, and the appalling decapitation of their caretaker, archaeologist Khaled al-Asaad, at the age of 82, in the midst of the armed conflict in Syria.

In this regard, according to Domínguez Michal, literary criticism needs a certain freedom: a freedom cultivated in close contact with the dead—among books—and one that must be practiced in the public square. Its task is historical: it consists of disseminating aesthetic and humanistic values that go beyond the transient nature of the market and the fleetingness of the contemporary.

Criticism is not synonymous with the review—its most elemental function—though the review forms part of the profession’s everyday reality. To reduce the critic’s task to passing functional judgment on whether a book is good or not is, according to Domínguez Michael, to deny the intellectual legacy passed down from the portraits of Sainte-Beuve, the invitation to reading of Borges, the almost theological commentary of Eliot, and the philosophical essays of Steiner. Criticism is a high art, and the review is just the most minimal of its manifestations.

Domínguez Michael’s pages are literary pages. The way he addresses a book or author is not based solely on thematic description or on syntactic or prosodic analysis: in his texts, he inserts relationships, anecdotes, profiles, and silhouettes. Altogether, they take the shape of a story that ends up shedding light on an idea. When addressing Dickens in Los decimonónicos (Ediciones UDP, 2012), he takes us into the office of a doctor he knows, who fruitlessly tries to get a spark or flame out of his lighters after their fuel has run out. We learn of a habit of useless collecting, of an illness that pulls him into the shadows, and of how this image leads him to recall the character of Dr. Manette from A Tale of Two Cities, who, during his years of imprisonment in the Bastille, keeps his mind occupied by putting together wooden shoes.

Critical Dictionary of Mexican Literature (1955-2010)

|

|

Books by Christopher Domínguez Michael in English and French

This drive toward criticism as independent knowledge is also made clear in the distance he keeps from the academy. While he recognizes that his education and readings came from masterful teachers—Steiner, Denis Donoghue, etc.—he rejects theoretical fashion and the linguistic turn, which he links with the anti-liberalism arising from an intellectual proletariat. As he sees it, contemporary academic criticism has invigorated a “school of resentment” (Bloom) that questions the humanist canon based on criteria foreign to literature: race, gender, identity. He is a foe not of the university, but rather of doctrinaire bondage, be it secular or ecclesiastical.

Here, Domínguez Michael’s liberal ethos comes into view: the critic is conservative in the enlightened sense of the term. He conserves the valuable parts of the past not out of nostalgia, but because there lies the aesthetic experience that allows for an understanding of the present. “We are doomed to turn to the school of the classics. That’s what they’re there for: so each generation can learn from them.”

His oft-criticized politicization is inseparable from his broad vision of literature: if literature is the criticism of life, the critic must extend it to history and politics. “I aspire to be a universal critic; I don’t see why a Latin American can’t be.” Of the many articles and essays he has written, most are pieces of a puzzle he has in his mind. These pieces, parts of an encyclopedic humanism, reveal a writer who seeks to pass down a map with which future generations might find their way. His Latin American condition adds a novel element to the predominantly Anglo-European gaze shared by the roster of literary essayists. His knowledge of Mexican literature, which he has explored in depth—and of the rest of the continent’s literature—leads him to integrate these authors into a dialogue with the Western tradition, not as a regional subgenre.

For working with this sort of intersection, he has been accused of Eurocentrism. He has also been reproached for the meager presence of women authors in his work. In his defense, he has said it is not a matter of meeting quotas, but of literary greatness. By placing Latin American authors—both men and women—in dialogue with the world, he follows the prerogative of a plural critical ambition, based on equality rather than difference, running counter to a literature that seeks to belong to a minority, regardless of which minority that might be: political, ethnic, or sexual.

When, in La sabiduría sin promesa (Ediciones UDP, 2009), he speaks of Bolaño, he speaks of Bolaño and Mexico. He speaks of the place where Bolaño spent the decisive years of his life, and of this place as a land of imagination. He then claims that, since Under the Volcano by English novelist Malcolm Lowry, no book has been written with Mexico as its setting as decisive as Los detectives salvajes.

He is critical of Spanish cultural hegemony and of Spain’s publishing market as a final arbiter, just as he is of the English-speaking world’s lack of interest in certain Latin American authors whom he considers crucial pillars of the canon. It is not easy to reduce Domínguez Michael’s puzzle: it expands in all directions. The lost paradise he finds embodied in nineteenth-century letters—Thomas Mann and his son Klaus, H. L. Mencken, and Octavio Paz; the short stories of Mariana Enriquez and the subtlety of El nervio óptico by María Gainza; the lyrics of Bob Dylan, a Mexico City sunset, and simply observing a flâneur in Paris. Unlike other crafts, the literary critic’s demands a permanent explanation of what it is and how it is practiced. “Some doubt that we critics, though we use the same language as poets or novelists, are writers.”

Domínguez Michael’s work handily erases this distrust, from magazines like Proceso to Letras Libres, passing through his biographies of Paz and Fray Servando Teresa de Mier. His books let us feel the pulse of a writer who does not regret having focused his own work on the work of others. And, as I see it, beyond agreements or discrepancies, his work is an exchange, a conversation with someone who obstinately shares our own enthusiasm.

Note: On May 5, 2016, the Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra of Saint Petersburg, conducted by Valery Gergiev, gave a concert at the Roman Theatre of Palmyra, Syria. The program included music by Johann Sebastian Bach, Sergei Prokofiev, and Rodion Shchedrin. Some saw the event as an act of symbolic restoration, but it was also criticized. Some considered it a misuse of music as political propaganda in the midst of an ongoing conflict.