Storyteller, columnist, PhD in Philosophy and visiting professor at the Universidad Autónoma de México, Andrea Mejía brings us a novel about country folk—“natural-born poets,” she says—whose mysteries merge among magic drinks, secrets and spirits, and roads that lead nowhere.

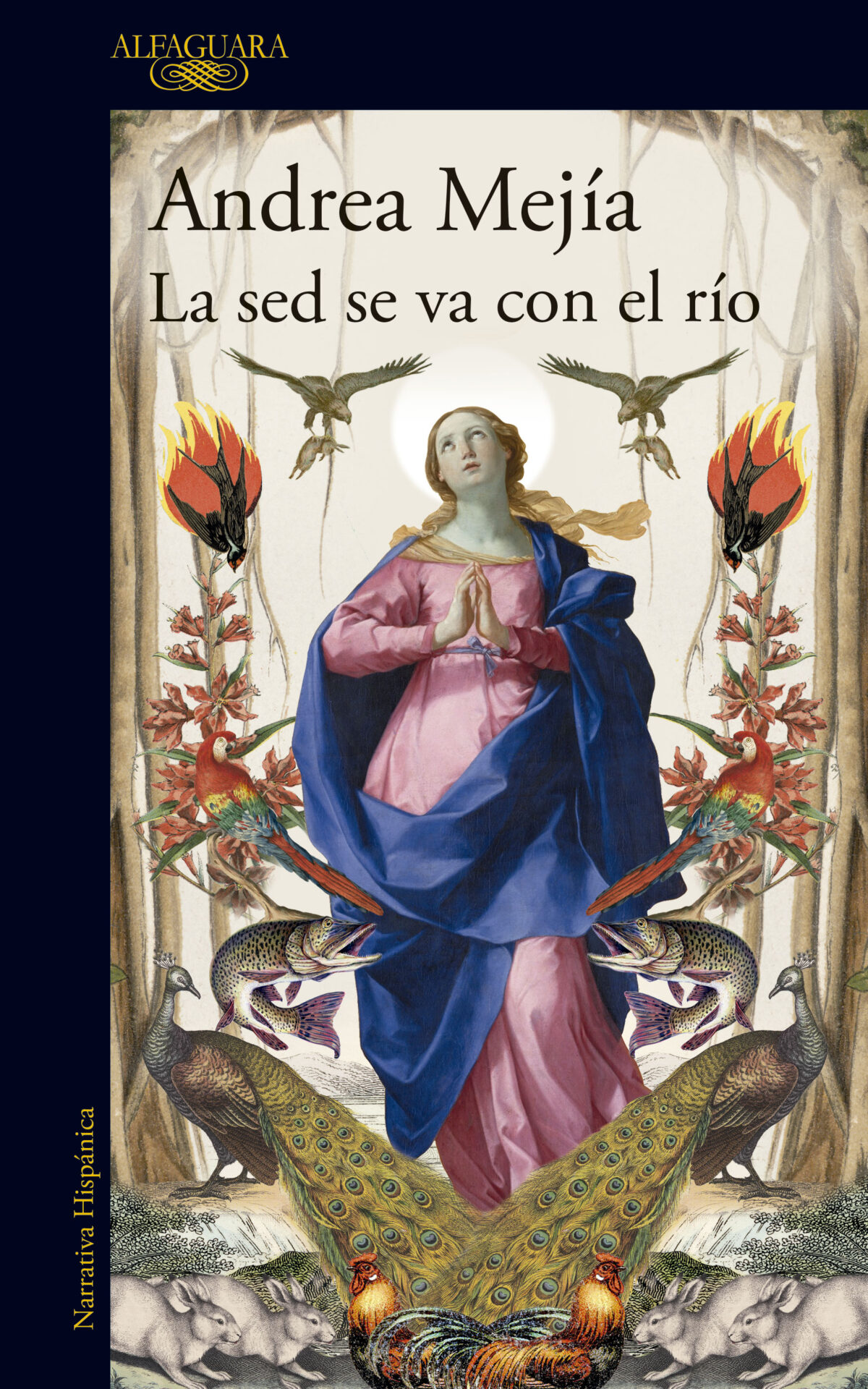

A novel of “phantasmagorias that are transforming the world” and a territory where the presence of water is sensed all over, in La sed se va con el río (Alfaguara, 2024), the settlers of a rural village next to the Nauyaca River spend the dark, gloomy days and calm, quiet nights as if time did not pass. Jeremías, a wise, blind man, but also a seer, delivers—aided by his bejuco liquor—visions, guesses about the future, omens, and spirits that show up unsummoned. Above, a large statue of the Virgin Mary observes with vigilant eyes, “alone on the mountain, white among the elements.” A constant, endless wait in lifeless, remote villages; the apathy; Heraquio and “Blackbird Legs” looking for the man—lost in the empty moor—who inherited the recipe for a drink that keeps the mystic secret; a fire, ghosts, and appearances from the past and the future, catastrophes and miracles: all these inform the mystery that Andrea Mejía narrates with an extraordinary air of the Andean Gothic.

Juan Camilo Rincón: How was it to construct this novel in terms of structure, dialog, the (dark, gloomy) atmosphere?

Andrea Mejía: The [novel’s] structure is not linear; it does not unfold as the events of the story occur. Instead, it is told just as the events were revealed to me. As the story went on, I told it in that same way. That is why it’s like a jigsaw puzzle that is put together in the end. For me there were pieces, holes, I did not know what had happened here or there, and in the end the structure or, rather, the entire landscape was completed. I set it in three parts whose axes are the characters. The first part’s is Jeremías, the second part’s axes are Lidia and “Blackbird Legs,” and the third’s is Esther. That disposition does follow a chronological order, because old Jeremías is the first to prepare the ancient recipe for the bejuco liquor, inherited from the indigenous people; then, Lidia receives the recipe from her grandfather, and she has such a tortuous story with Blackbird Legs; and then comes Esther, the last one to arrive in this isolated world and walk through the canyons of the Nauyaca River.

J.C.R.: How did you work on the dialogues and the atmosphere?

A.M.: It seems to me they are like a counterpoint in their brevity; they are almost lapidary. Generally, country folk do not talk much, in contrast to the profusion and exuberance of nature, which gives the novel its whole atmosphere. It [nature] is the novel’s air; the air in the sense of space; what is breathed, lived, walked through. Then, on the one side, there is this continuous flow of nature, which is like the flow of the river, of the elements, the alternance between the rainy season and the dry season, and, on the other side, there is the precision and concision of dialogues among these people, natural-born poets, who talk little.

J.C.R.: Speaking of the nature that you build up, one feels one is amid a Gothic of the Andean moors: there is always something dark, humid, and dense, a permanent desolation, although some happenings occur on sunny days.

A.M.: On the one hand is the presence of the moor, and the harshness of the landscape, in contrast to the bountiful, fertile exuberance of the vegetation and animals on the riverbanks. That moor was actually an imaginary overlapping of the riverside territory and the canyons, where there aren’t any roads, and it is easy to get lost. In my experience, first comes the moor, then the river, and third the rainforest, but I would love for them to merge into one single territory: the territory of my imagination and my experience. That moor seems fundamental to me, because it is empty, and at some point, it becomes the land of death and the dead. There, in the end, Blackbird Legs, Jeremías, and Heraquio meet. The moor is called Isvara —the name of the Lord in Hinduism, the god of a mental state of emptiness, of the absolute. The moor, then, plays a terrifying and sinister role, along the lines of what is distant, of another territory.

J.C.R.: And on the other side is life, with all the animals, the river…

A.M.: And nature, which does nothing but grow in every way. Characters shift between life and death, between the moor above and the riverbanks below, blessed by nature. I also think you felt the novel is ambiguous in general. Its plot is ambiguous and has a darkness to it, its characters are ambiguous. For example, Jeremías is very free, he’s always cracking up, but he’s also a very old guy, very dark. In him, light and darkness come together: he is free and joyful and, precisely because of that, he can welcome within him the darkness of his mouth, of his self. Why does he do what he does? Why does he get these men drunk on bejuco? Why is he not afraid of death? Why does he want to leave? It is because he’s an old man, very close to liberation, or already liberated.

J.C.R.: The bejuco liquor is also ambiguous.

A.M.: Sure, because it is a drink that provides visions, that is, it allows us to see, to know what’s real from a much wider perspective than our ordinary mind, stuck in its routines and habits. But this drink also has a darkness to it; it is a hard, difficult, drunkenness. Violence is also present and adds density—gothic density, we might say—to the situation; we see it in this figure of men as a collective, who intend to set La Golondrina on fire, all moving like one single body, on a very dark night in Sanangó. That village, the fact of being isolated, the hardships of life, the loneliness of the countryside, all of that is there, joining the pure force of desire, of love. As if everything were there, because there is not one single reality.

J.C.R.: Throughout the novel one guesses and directly perceives the presence of the river water as a pillar of the story: [the water is present] in the humidity of the atmosphere, the booze, the desire to drink the bejuco liquor…

A.M.: What you say makes me think that hard reality, cosified, is the solid, whereas the water is what flows, runs and winds down. Gods are also made of stone, mountains are stone, but water is a deity because life was born from it, we can live because of water.

There is also this idea that mystic beverages are always associated with wine, the drunkenness of wine. In the Sufi poetic tradition they talk about the wine of God’s drunkenness. I think in Rumi they always end up at a tavern, the place where they meet with God, because they get drunk and lose the boundaries between the individual and reality or the whole. The blood of Christ turns into blood… It is important for it to make you drunk, and to be liquid, that it not be a solid food. I think it’s great that the magic bejuco turns into booze.

J.C.R.: A magic bejuco that is also related to bad spirits, malignant changes, visions, dizziness, men who go progressively crazy, and get drunk in a way that is not “normal.”

A.M.: It is a different kind of drunkenness, but I did not want it to be only mystic drunkenness. I wanted it to also be like being wasted, something physically taxing. In the end, it may be the same drunkenness, but it is disastrous, and it makes men weird: it does not always make them angelic and beatific, but rather it makes them violent. On the other hand, it is this mystic drunkenness that leads you to see from nowhere or from the mind of God, which is the mind of all. It [the drunkenness] has both elements, and I think this was important to show; that it was not just a miraculous, curative drink, but that it was ambiguous, like everything is. And they grow fond of visions, because what is the point of life without them? When they set La Golondrina on fire, these men do not realize they have been left empty. The beverage is addictive because they cannot go without the visions it provides. How could they go back to ordinary aguardiente?

J.C.R.: The novel has Rulfian undertones, especially regarding the relationship with the dead and the way of talking to them.

A.M.: Evidently, Juan Rulfo is a very important reference point. However, beyond that [influence], I believe, just as there are rivers in this territory—they are named by the free faculty of imagination, like the Nauyaca River, and they are rivers that ought to have sonorous, indigenous names, and suddenly they flow into the Cauca River, a real, factual river, there on the map—the same thing happens with the living and the dead, separated by an abyss.

You and I are factually in this world, and we can prove our existence, whereas our dead are not here, they are an absence, but they do exist in another plane of reality. If reality was not as separated between what is provable and materially existing in our perception and what exists in a different way or in other planes of perception, or in other planes of the real, there could be communication between those two worlds. That is what happens in great epic stories: the seers, the heroes, like Odysseus or Dante, travel and shift between the world of the living and the world of the dead. Descending to the world of the dead is an almost shamanic experience that we should have—so it seems—in order to access a full knowledge of reality.

J.C.R.: And you put up that bridge of sorts between the two planes…

A.M.: It seems to me that it was rather freeing to not have them separated like worlds that cannot have contact, but rather with a constant shifting. If you remember, there is a day when the Fiesta de las Lumbres is celebrated, when the dead go through the canyons of the river and arrive at the houses, where they have food for them. This happens, with variations, in all cultures. The Day of the Dead in Mexico, for example. In Japan, there is one day when food should be served to the dead, who are also present in altars at home… That presence of the dead in the lives of the living, and the other way around, seemed nice to me—maybe the dead have altars for us, where we eat when we visit them. I appreciate that relationship between life and death because ultimately there’s a continuity, not a separation.

J.C.R.: There is something you’ve mentioned tangentially, and I find it interesting: How did you come up with the names of characters and places? Jeremías, Nardarán, White Crown, Blackbird Legs, Zacarías, Zambrano: there’s a musicality of sorts.

A.M.: I believe that, intuitively, I was after the sound, the sonority, more than the meanings [of those names]. Recently someone made me realize there were several Biblical names in the novel: Jeremías, Esther, Sara; but that was not the point for me; it is more the sound [of those names]. “Jeremías” has the strength of an appearance, just by saying it. It was different in each case. Heraquio is a fitting name, from an actual farmer who welcomed me into his house, in the canyons of a river—which inspired this imaginary river, and without which it could not have existed. It is a lovely name, also because it is a lot like Heraclitus, who is like the philosopher of the river, and it comes from an actual farmer, of flesh and bone, from the world of the living. The others appeared in different ways. Lidia sounds like Lidilia, which was my grandmother’s name: perhaps there is something unconscious there [in that choice]. Esther also fascinates me for the strength with which it resounds, but there is nothing more than that.

J.C.R.: Where does “Blackbird Legs” come from?

A.M.: That is a funny story: at the beginning his name was Herminio Cruz; he already had that surname, I think it was his destiny to carry something in his back, but Hermenio and Heraquio were quite similar. My editor, my agent, made me notice that it was difficult for the reader to remember two names starting with the letter “H,” which were so similar, especially when the characters go together, so I changed it to Lautaro Cruz. But the character only began to exist when he was called “Blackbird Legs.” That nickname was key for him to find his true character and his true reality. “Blackbird Legs,” it seemed to me, was a name that found his true character, and that’s a miracle.

J.C.R.: Jeremías’s visit is key to the novel, wearing a white cloth over his eye. There is something oracular there, in the ghostly images, the spirits, the visions, the omens, the premonitions of curses. Let’s talk about the novel’s mythology.

A.M.: I believe mythology, the power of myths, does not come from me turning to a book to inspire me and to think how Jeremías is going to be. Rather, myths, for some reason, manage to crystallize forms or figures that are very powerful and very archaic. If Tiresias, the fortune teller, the seer, is also the seer of Sophocles—of the tragedy of Oedipus—and he is blind; if the seer in the Odyssey is also blind, none of that is in vain; the point, then, is not to make your character who has visionary powers intentionally blind because it’s an image institutionalized by the history of literature or the history of mythology, but rather because there is a connection between not being able to see with the eyes and being able to see with the mind. The barasanos, an ethnic group from the Vaupés rainforest, say they do not see with their eyes, but with their minds; shamans see with their mind. I was not thinking consciously about this whole matter of not seeing with the eyes, but I think that’s why visionary, very wise people are blind, literally or metaphorically, with respect to the eyes we normally use to see; it’s another way of seeing.

J.C.R.: Going back to what you were saying about the Greeks, I feel there is a shared misfortune in this novel, and an inevitable tragedy that is carried on, both in a material and a symbolic manner: the fire, the absence, the town with that “ring of immobility surrounding it,” the statue of the Virgin high above, observing the curse…

A.M.: I do feel—because you make me see it—that there is a game between the collective and the individual. Certain figures carry something that belongs to everyone. For example, “Blackbird Legs” carries a guilt that belongs to all men from the village, and he is the only one who—as you rightly say—materially and physically assumes the weight of that guilt as his own. It is like the concentration of forces—which are multiple and transpersonal, which are beyond—in one single figure, in one individual. Then you talk about the Virgin, and I think that is very accurate because, in that statue, magical and mystical forces are concentrated that travel through all the canyons, throughout the river. That is why rural folk say the Virgin has three bodies: one is invisible, another is only visible to those who are in a state of misfortune, and one is visible.

I think it is very nice that you have associated this kind of incarnation of guilt with a character, as also happens in Greek ideas. Oedipus is expiating a guilt that goes far beyond his own because he was also innocent; he didn’t know what was happening or what he was doing, he was simply assuming ancestral forces; the same happens with “Blackbird Legs.” The Virgin is the incarnation or materialization of forces that go far beyond that statue.

J.C.R.: In the novel there is a relationship with the construction of geography from the countryside. How was it to write this novel, considering your own experience of living in the countryside?

A.M.: I live in a very rural region, and I am very grateful for that. I am surrounded by rural folk who look like characters from Rulfo and that is wonderful; they are truly beautiful. I am dazzled every time I meet one and he starts talking to me; it’s like I don’t even have to write it down, the book is already there. I live on a path near Choachí, which is very high up and very wild. It is a forest that has been preserved quite a bit; I walk with my dog through those woods, and there I nourish my writing. I don’t know what it would be like to write in the city; I don’t know if I would have the same energy, the same devotion. The experience of nature in even wilder and more open places like the rainforest has been fundamental; they have been moments of vivification, of fullness of life where I receive so much energy and strength.

Translated by Lorena Iglesias