Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt from the chapter “Under Western Eyes: Visiting Friends & Artists” of Chakravarty’s forthcoming book, The Tree Within: Octavio Paz and India, Penguin Random House, 2025. It is published here with permission from Penguin Random House India.

Ever since September 1963 when Octavio Paz settled down to his spacious bungalow in New Delhi as Mexico’s Ambassador to India, he had been pleading with his friends in Paris to visit him. The large, red-brick colonial-style house had five bedrooms, two sprawling gardens with five servants waiting on him. In the summer of 1964, just before his return to India with Marie-José Tramini—a French woman whom he had met in India who would become his second wife—Paz spent some time with Julio Cortázar in Paris to introduce his new girlfriend. Cortázar had been living in Paris since 1951 as a professional translator for UNESCO and for several publishing houses. He was a gentle giant, six and a half feet tall, and spoke Spanish with a mild French accent as he was born in Belgium. His first wife, Aurora Bernárdez, a sharp woman with whom he had a passionate relationship over fifteen years, was also a translator at the UN. Cortázar mentioned their meeting in a letter to a friend:

Octavio spent a few days in Paris and returned to India with a beautiful girl, which amply justified the trip. From there, he wrote me some lines at the end of the year. Looks like he is having a great time.1

Since Paz and Cortázar are two of the greatest figures of Hispanic literature, their co-living in a distant culture over a period of two months merits a closer look at how it impacted their creative lives.

By the time the Cortázar couple accepted Paz’s invitation in early 1968 in relation to a UN Conference on Trade and Development in Delhi, the Argentine writer had already become an international celebrity. Even before their India trip, Cortázar and Aurora had drifted apart, but they still decided to go ahead for the thrill that the journey promised. It came at an opportune moment and was planned well ahead of time:

In February-March we will go to India with the UN. It will be magnificent because Octavio has written to me offering us accommodation—he has a large house—and you can imagine what it will be like to have him as a guide and companion in New Delhi.2

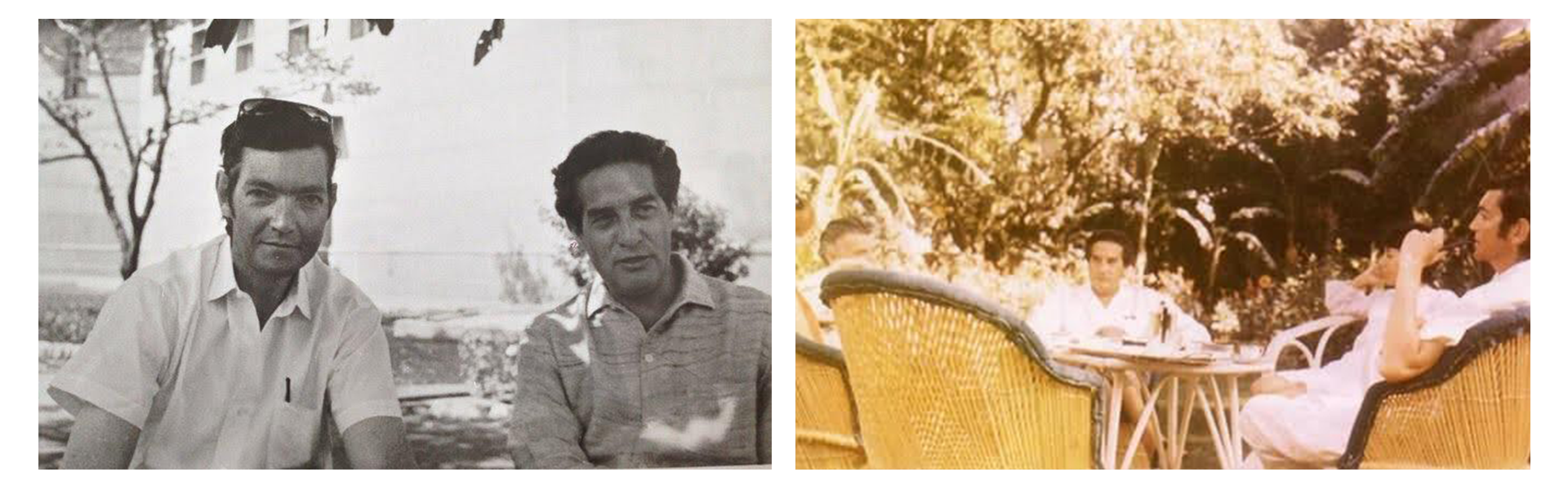

Paz and Cortázar were both born in 1914, and grew up under similar formative circumstances, literary and political. Both were under the spell of Romantic poetry in their early days and they both creatively assimilated elements of surrealism and existentialism in their works while maintaining a critical distance with French culture. Cortázar became increasingly polarised towards the political left after his trip to Cuba in 1963, which was also one of the reasons for the rift with his wife Aurora, who despised the Cuban revolution.3 Despite having widely different political stances on the Latin American politics of the day, and though they represented “aesthetic parallels,” a life-long friendship blossomed between the writers and their wives.4

Already in 1963, Cortázar paid tribute to his friend by quoting one of Paz’s short poems in Rayuela [Hopscotch]. Paz considered Cortázar among the Latin American greats, alongside Rulfo, Borges and Neruda. Cortázar declared Paz as “the seafaring star of Latin American poetry.” Paz’s Harvard lectures (1971-72), published as Los Hijos del Limo (“Children of the Mire,” 1974), were movingly dedicated to Cortázar:]

A Julio, más cerca que lejos, en un allá que es siempre aquí, Octavio.

[To Julio, much closer than far away, in a there that is always here, Octavio.]

Cortázar expressed his discomfort at soliciting hospitality for the unusually long period of two months:

We live in Octavio Paz’s house, in the embassy zone. The Mexican flag floats over the porch of this beautiful house. We have so many rooms and servants for ourselves that we feel uncomfortable, embarrassed, and only the affection of Octavio and his wife saves us a little from a kind of life for which I was not born.5

Cortázar wrote letters continually to his friends in Paris. He dwelt on the unreality of the life he was living in the lap of luxury with a dream combination of emotional warmth and the most exciting intellectual company:

We own a large bedroom, a bathroom, a living room with a library from where I am writing this letter to you, and a room to store clothes and suitcases. On top of that, we have independent access to the garden and the street. As you can see, this is nirvana. Octavio and Marie-José have gathered a fabulous collection of Indian objects and paintings; so, living here is more than pleasant. My meetings with Octavio are quite memorable, and I learn a lot from him about Indian politics, critical Marxism (which I am lacking) and Latin American literature. Last night he spoke to me for two hours about José Vasconcelos and I can assure you it was worth it.6

Unlike Paz, he did not have any Indian friends. The ones he met at his workplace heightened his awareness of cultural difference:

Here in New Delhi, there is the sun and there is Octavio Paz… I am writing to you from a humid office, with big-eyed Indians who come and go, carrying out vague tasks: one passes a cloth over the arms of the chairs, another passes a wire through the locks of the desks and makes strange notes on them, another looks at the plugs (which do not work), shakes his melancholic head and leaves. Big, beautiful ants pass by. And we seem like what we are: the barbarians of the West… Kipling was right: East and West never shall meet.7

The Argentine couple shivering in the Delhi cold was keenly looking forward to enjoying the tropical heat.

At the breakfast table, the Paz-Cortázar couples spent a lot of time discussing poetry. “What else can they talk about?” wondered Aurora in a letter to her friend. Discussions about politics often led to what Cortázar called “Octavio’s anti-Stalinist neurosis that he projects in all directions.”8 But there was a third topic in which their wives merrily joined: making plans for their trip together across India. They made full use of their weekends from their tight UN schedules. One weekend they travelled to see the erotic temples of Khajuraho accompanied by Paz’s live commentary on his favourite subject. Cortázar wrote to a Latin American friend:

You will have seen in the art albums the fabulous erotic sculptures of Khajuraho. What the albums do not convey is the honey-hue [of the stone], the air that surrounds them, the perfume emanating from the trees around the temples, and the presence of the people, the birds, the time. Khajuraho [represents] eroticism as a transcendence. For long hours, I spoke to Octavio about this.9

“That world, that way of living,” Aurora wrote to a friend, “that idea of life so different from ours, I don’t know if it’s better, but it is so different.”

Another weekend they travelled to Agra and Fatehpur Sikri; yet another to Jaipur. During certain weeks, they did night shifts at the UN, which allowed them to explore Old Delhi during the day. In the middle of “Octavio’s busy diplomatic schedule of cocktails which he dislikes,” there was a reception at the Cuban embassy with Havana rum and cigars, which was a welcome relief. Paz took them to art exhibitions and music concerts, which are plentiful in Delhi in the winter months. On one occasion, he even took them to the nearby Sunder Nagar Zoo, where Cortázar was thrilled to see a rare, white Bengal tiger. Readers of Cortázar’s short story “Bestiario” will recall a tiger roaming around the grounds where a child is sent for a summer stay. Since tigers do not exist in South America, the real-life encounter with a Bengal tiger was a fulfilment of Cortázar’s fantasy.

The couple’s itinerary involved travelling northwards from Delhi to Nepal. When the conference ended, they took a train to Calcutta and proceeded to explore the Konark temple of Orissa on the east coast, and then descended to Madras to visit Mahabalipuram and particularly Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) further down, a place that was part of Cortázar’s childhood fantasy. From Ceylon, they travelled upwards and westwards to Bombay, from where they made a three-day trip to the caves of Ajanta and Ellora. Wherever Cortázar went, Paz thrust “fabulous books of Indian art” into his arms so that he adequately educated himself before visiting the sites.

During his stay with Octavio Paz, the two had many conversations about the playfulness of form. It provoked Cortázar to write a collection of poems titled 720 Círculos [720 Circles]— signed “Delhi 1968”—which declared at the outset that the “poem is circular and open-ended at the same time.”10 It was open-ended because the reader could start at any point and then come back to the point of beginning, thus completing a circle. While Cortázar was dabbling with poetic form, in the adjacent room Paz was writing a similar experimental collection of poetry titled Topoemas where he was exploring the topographical aspect of the printed word in poetry.

Though Cortázar often did not agree with Paz’s opinions, he was captivated by the lucidity of his arguments and insights. What amazed him most about his friend was his passion for exploring new paths in poetry. Paz’s Blanco, which was also initiated during Cortázar’s stay, was “the result of a long Indian meditation, on one hand, and structuralist [reflection] on the other.”11 Paz soon moved on to a series of “rotating” poems which were printed with a system of punched cards that left it to the reader to decide how one wanted to read the text.

Cortázar carried with him the galley proof of a landmark novel of the boom, the Cuban poet José Lezama Lima’s novel, which he handed over to Paz after reading it. Paz instantly recognised it as a masterpiece and wrote to Lezama Lima:

I am reading Paradiso slowly, with growing astonishment and dazzlement. A verbal edifice of incredible richness; rather, not an edifice but a world of architectures in continuous metamorphosis and also, a world of signs—noises that are configured into meanings, archipelagos of meaning that is made and unmade—the slow world of vertigo that revolves around that untouchable point that lies between the creation and destruction of language, the point that is the heart, the nucleus of language…12

The novel was diligently edited by Cortázar and published from Buenos Aires in 1968 because Lezama Lima was increasingly marginalised in Cuba for his homosexual themes and apathy towards the revolution. Paz was aware how much weight his words carried and he leveraged it judiciously to encourage promising young writers across Latin America.

The sheer joy of the time the two writers and their wives spent together in India was best captured by Cortázar’s handheld 8mm camera, with which he filmed the Holi festivities at the Paz residence. Though only a two-minute clip has survived, the camera seems to have changed hands several times even over that brief duration. At one point, one sees Paz’s forehead smeared with red powder, dancing in his garden with the maids, their children, and other local kids. Cortázar is also daubed with paint and dances in tandem with Paz with Mexican folk-dance moves (such as la yenka, usually danced by children).

The Cortázar couple left India the day after Holi, leaving a huge void in the lives of Paz and Marie-José. Dwelling in the wistful afterglow, Paz wrote a letter to his friend, Carlos Fuentes, that provides a vivid image of his state of mind:

Aurora and Julio just left. Today is the day of Krishna. In the morning my hair and face were smothered with coloured powder. The days are so perfect that I am overwhelmed by laziness: I just want to live, nothing more. Like the lizards or Marie-José’s cats… Last week, I made four solid poems (poetry is made, not written). Rita and Carlos, you guys are traitors! If you were here, you would have seen the moon, listened to the drumbeats that celebrate the erotic games of Krishna with his troupe of gopis, you would have devoured curry, chapatis and mangoes in the garden; in the evening, we would have drunk bhang together (a mild alcohol) and at night you could have listened to Julio Cortázar reading aloud a play by a Mexican writer who, some say, is talented. I think his name is Carlos Fuentes.13

The presence of Buddhist and Hindu thought is palpable in Cortázar’s fiction in terms of their exploration of metaphysical and existential questions where characters are in pursuit of an elusive sense of enlightenment. He had planned to name his novel Hopscotch “Mandala,” as it goes around in circles in pursuit of a centre. In it, characters delve into discussions about the nature of reality, the self and consciousness with inherent intimacy with Indian thought. Later, he felt that, as the title of a novel, “mandala is too pedantic.” Nevertheless, when his characters use phrases such as “freedom from suffering,” “enlightenment” and “traversing the inner path,” they are clear allusions to Buddhist ideas. Likewise, his narrative structures are dialectic, based on a system of oppositions, where the opposites merge and annul each other.

In the years that followed, Cortázar met Paz in Paris and in Mexico City. Both dedicated poems to each other. In 1971, the Argentine wrote a beautiful text for his friend and called it “Tribute to a Starfish.” When Cortázar died in 1984, Paz wrote a moving funeral eulogy.

1 Letter to Amparo Dávila, Paris, 23 Feb. 1965. Source: zonaoctaviopaz.com

2 Letter to Jorge Edwards, 2 Nov. 1967.

3 Paz’s position in relation to the highly polemical Cuban revolution was astutely articulated in a letter he wrote to a literary critic: “I am with the Cuban revolution for all that it owes to José Martí but not to Lenin.”

4 Anthony Stanton’s phrase.

5 Letter to Jean Barnabé, 30 Jan. 1968.

6 Letter to Eduardo Jonquières, 17 Feb. 1968.

7 Letter to Arnaldo Calveyra, 1 Feb. 1968.

8 Letter to Omar Prego, 23 September, 1981.

9 Letter to Julio Silva, 20 Feb. 1968.

10 Published in Revista Iberoamericana, issue 74.

11 Cortázar’s letter to Eduardo Jonquières, 6 March, 1968.

12 Letter to Lezama Lima, 12 June, 1968.

13 Letter to Carlos Fuentes, 16 March, 1968.