Alejandra Costamagna: El sistema del tacto [The system of touch]

Alejandra Costamagna was a finalist in the last edition of Spain’s prestigious Premio Herralde, and now she returns with a resounding novel in which the system of touch is articulated around the idea of roots. Its protagonist, Ania, crosses the Andean mountain range to say goodbye to her uncle Agustín, who is dying. Throughout this journey, and the arrival of the central character to her destination, Alejandra Costamagna sews a thread of broken temporality in which episodes of the past and present intertwine to form a common fabric. Here, the characters return to the sensory stimuli that always connected and limited them.

Alejandra Costamagna was a finalist in the last edition of Spain’s prestigious Premio Herralde, and now she returns with a resounding novel in which the system of touch is articulated around the idea of roots. Its protagonist, Ania, crosses the Andean mountain range to say goodbye to her uncle Agustín, who is dying. Throughout this journey, and the arrival of the central character to her destination, Alejandra Costamagna sews a thread of broken temporality in which episodes of the past and present intertwine to form a common fabric. Here, the characters return to the sensory stimuli that always connected and limited them.

Alejandro Zambra: No leer [Do not read]

An inventory of sympathies, phobias and whims, delicious albums of quotations, frustrated projects and declarations of love—to photocopies, to the penumbra, to the drafted word, to Chilean poetry and to the “orilleros” of the Latin American boom—No leer is a passionate, strange, funny, and melancholic book, and Alejandro Zambra is one of the most talented and recognized Latin American writers of recent times. “In these pages, there are sketches, essays, stories camouflaged in essays (in the style of Borges) and an intense way of reflecting and enchanting readers, as only writing that escapes the commonplace can” (Fabián Casas, Perfil).

An inventory of sympathies, phobias and whims, delicious albums of quotations, frustrated projects and declarations of love—to photocopies, to the penumbra, to the drafted word, to Chilean poetry and to the “orilleros” of the Latin American boom—No leer is a passionate, strange, funny, and melancholic book, and Alejandro Zambra is one of the most talented and recognized Latin American writers of recent times. “In these pages, there are sketches, essays, stories camouflaged in essays (in the style of Borges) and an intense way of reflecting and enchanting readers, as only writing that escapes the commonplace can” (Fabián Casas, Perfil).

Antonio Ortuño: Olinka

Olinka describes the crisis of a business clan in Guadalajara, the capital and paradise of money laundering. There, the Flores family built their urbanization inspired by an old idea of Dr. Atl, who dreamed of creating a city for scientists and artists. But Mexican reality turns utopias into bloody mockeries, and the multiplication of real estate projects is one of the clear signs of prevailing corruption. Antonio Ortuño, one of the best Spanish American narrators of his generation, explores in this novel an irrepressible problem: gentrification and the role of dirty money in this process. And he does so with implacable prose, which strips each character bare and dissects the chaos of contemporary cities.

Olinka describes the crisis of a business clan in Guadalajara, the capital and paradise of money laundering. There, the Flores family built their urbanization inspired by an old idea of Dr. Atl, who dreamed of creating a city for scientists and artists. But Mexican reality turns utopias into bloody mockeries, and the multiplication of real estate projects is one of the clear signs of prevailing corruption. Antonio Ortuño, one of the best Spanish American narrators of his generation, explores in this novel an irrepressible problem: gentrification and the role of dirty money in this process. And he does so with implacable prose, which strips each character bare and dissects the chaos of contemporary cities.

Ariel Magnus: Ideario Aira [Aira’s essential ideas]

This is a dictionary of ideas about the literary work of César Aira, and it delves deeply into the author’s extraordinary universe. Aira’s novels are full of grand ideas: transparent storms, paintings made with the light of passing cars, magic gloves that give their wearer the virtuosity of the great pianists, a calculation to know how many taxis there are in the city, an educational system in which children go to university and adults end up in kindergarten. Here, Magnus compiles several unusual occurrences, bizarre objects, and more or less scientific theories of the great Argentine writer.

This is a dictionary of ideas about the literary work of César Aira, and it delves deeply into the author’s extraordinary universe. Aira’s novels are full of grand ideas: transparent storms, paintings made with the light of passing cars, magic gloves that give their wearer the virtuosity of the great pianists, a calculation to know how many taxis there are in the city, an educational system in which children go to university and adults end up in kindergarten. Here, Magnus compiles several unusual occurrences, bizarre objects, and more or less scientific theories of the great Argentine writer.

Arturo Pérez-Reverte: Una historia de España [A History of Spain]

Throughout the 91 chapters plus the epilogue that make up this book, Arturo Pérez-Reverte narrates the main events that occurred from the beginnings of history to the end of the Transition with a subjective view, constructed with exact doses of readings, experience, and common sense. “The same vision with which I write novels and articles,” says the author; “I did not choose it, but it is the result of all those things: the vision, often more sour than sweet, of someone who, as a character in one of my novels says, knows that being lucid in Spain always implies a lot of bitterness, a lot of loneliness and a lot of hopelessness.”

Throughout the 91 chapters plus the epilogue that make up this book, Arturo Pérez-Reverte narrates the main events that occurred from the beginnings of history to the end of the Transition with a subjective view, constructed with exact doses of readings, experience, and common sense. “The same vision with which I write novels and articles,” says the author; “I did not choose it, but it is the result of all those things: the vision, often more sour than sweet, of someone who, as a character in one of my novels says, knows that being lucid in Spain always implies a lot of bitterness, a lot of loneliness and a lot of hopelessness.”

Ave Barrera: Restauración [Restoration]

Restauración is the scary horror story of a young renovator trapped between the memories of an old house in Mexico City and the sinister plans of a photographer obsessed with recreating the scenarios of the novel Farabeuf by Salvador Elizondo. This work highlights some of the conflicts that women have experienced in the recent past and confronts them with the present. By focusing the narrative on the perspective of women and emphasizing their problems, this novel questions the way in which female characters in literature have often been made invisible, silenced, or idealized for centuries.

Restauración is the scary horror story of a young renovator trapped between the memories of an old house in Mexico City and the sinister plans of a photographer obsessed with recreating the scenarios of the novel Farabeuf by Salvador Elizondo. This work highlights some of the conflicts that women have experienced in the recent past and confronts them with the present. By focusing the narrative on the perspective of women and emphasizing their problems, this novel questions the way in which female characters in literature have often been made invisible, silenced, or idealized for centuries.

Bernardo Esquinca: Las increíbles aventuras del asombroso Edgar Allan Poe [The incredible adventures of the amazing Edgar Allan Poe]

A novel that expands the limits and landscapes of writing in an audacious exercise that is both a tribute and an approach to Edgar Allan Poe, the father of the police story and the American horror story. In these pages, Poe is shown as a human being, still far from the greatness that would consecrate him and the abyss that would consume him; a young man who curiously watches the world and its secrets, and who is always ready to embody in his life the exciting and obscure literature that he is destined to create. Undoubtedly, this novel is an endearing and moving portrait of one of the tutelary figures of Bernardo Esquinca’s own writing.

A novel that expands the limits and landscapes of writing in an audacious exercise that is both a tribute and an approach to Edgar Allan Poe, the father of the police story and the American horror story. In these pages, Poe is shown as a human being, still far from the greatness that would consecrate him and the abyss that would consume him; a young man who curiously watches the world and its secrets, and who is always ready to embody in his life the exciting and obscure literature that he is destined to create. Undoubtedly, this novel is an endearing and moving portrait of one of the tutelary figures of Bernardo Esquinca’s own writing.

Edurne Portela: Formas de estar lejos [Ways to be far away]

The characters of this novel, Alicia and Matty, meet in a small town in the southern United States, where they fall in love and start a life together. They move in a world of shared solitudes in which violence and abuse are silently concealed, while they live in supposedly safe spaces such as one’s own home or university. Alicia tries to adapt to this new life, and she finds her place in this world and leads a happy life with Matty. However, in a context very close to the limits between distance, reality, and desire, a new violence is growing, which does not always explode into blows, and which affects Alicia in all aspects of her life, gradually wearing her down and diversifying their ways of existing in distant places.

The characters of this novel, Alicia and Matty, meet in a small town in the southern United States, where they fall in love and start a life together. They move in a world of shared solitudes in which violence and abuse are silently concealed, while they live in supposedly safe spaces such as one’s own home or university. Alicia tries to adapt to this new life, and she finds her place in this world and leads a happy life with Matty. However, in a context very close to the limits between distance, reality, and desire, a new violence is growing, which does not always explode into blows, and which affects Alicia in all aspects of her life, gradually wearing her down and diversifying their ways of existing in distant places.

Gerardo Fernández Fe: Moleskine Sergio Pitol

“In a brief diary titled Moleskine Sergio Pitol, Gerardo Fernández Fe develops a very personal encounter with the novels and stories of the Mexican writer, connecting them in stages with readings of other authors undertaken on sleepless nights, taking advantage of his sleeplessness to relate to them, and communicating with the author with whom he shares that moment of maximum lucidity, in the dark moments of the night.” As Reina María Rodríguez says, at every moment of this journey through fragments, seen through the writing of Fernández Fe, not only the obsessions that appear in Pistol’s narrative are unveiled, but there we see an intimate approach in which two authors connect through an investigative passion.

“In a brief diary titled Moleskine Sergio Pitol, Gerardo Fernández Fe develops a very personal encounter with the novels and stories of the Mexican writer, connecting them in stages with readings of other authors undertaken on sleepless nights, taking advantage of his sleeplessness to relate to them, and communicating with the author with whom he shares that moment of maximum lucidity, in the dark moments of the night.” As Reina María Rodríguez says, at every moment of this journey through fragments, seen through the writing of Fernández Fe, not only the obsessions that appear in Pistol’s narrative are unveiled, but there we see an intimate approach in which two authors connect through an investigative passion.

VVAA. Edited by Antonio López Ortega, Miguel Gomes and Gina Saraceni: Rasgos comunes. Antología de la poesía venezolana del siglo XX [Shared traits. Anthology of twentieth-century Venezuelan poetry]

If there is a dominant literary genre in Venezuela, it is undoubtedly the poetic, and a reading of twentieth-century Venezuelan poetry shows an admirable thirst for modernity and cosmopolitanism. Perhaps one of the main reasons to offer an international audience the comprehensive look that this anthology proposes corresponds to what Álvaro Mutis said about the poetry of the Venezuelan Juan Sánchez Peláez, labeled as the “best kept secret in Latin America.” One of his emblematic books, Rasgos comunes, gives this volume its title, to emphasize that there are more convergences than disparities. A bodily sensation is what remains after this reading. A sensation that the best country is the one expressed here.

If there is a dominant literary genre in Venezuela, it is undoubtedly the poetic, and a reading of twentieth-century Venezuelan poetry shows an admirable thirst for modernity and cosmopolitanism. Perhaps one of the main reasons to offer an international audience the comprehensive look that this anthology proposes corresponds to what Álvaro Mutis said about the poetry of the Venezuelan Juan Sánchez Peláez, labeled as the “best kept secret in Latin America.” One of his emblematic books, Rasgos comunes, gives this volume its title, to emphasize that there are more convergences than disparities. A bodily sensation is what remains after this reading. A sensation that the best country is the one expressed here.

Javier Padilla: A finales de enero [At the end of January]

In the mid-sixties, some Spanish universities saw a mobilization, increasingly organized and resolved, against the dictatorship of Franco. This novel reconstructs the details of a student revolt—no less intense than May 68 in France—and narrates the commitment to freedom of so many young people who made history and suffered the consequences, who faced beatings and prison sentences while they fell in love and discussed Marxism, psychoanalysis, and free love between beers and tobacco. This story of a regime that mercilessly repressed those who sought the beach under the cobblestones reminds us of all the fragile beginnings of the Transition to democracy.

In the mid-sixties, some Spanish universities saw a mobilization, increasingly organized and resolved, against the dictatorship of Franco. This novel reconstructs the details of a student revolt—no less intense than May 68 in France—and narrates the commitment to freedom of so many young people who made history and suffered the consequences, who faced beatings and prison sentences while they fell in love and discussed Marxism, psychoanalysis, and free love between beers and tobacco. This story of a regime that mercilessly repressed those who sought the beach under the cobblestones reminds us of all the fragile beginnings of the Transition to democracy.

Juan Carlos Chirinos: Los cielos de Curumo [Curumo’s skies]

Los cielos de Curumo [Curumo’s skies] is a narrative arranged as a house of cards in which the lives of five friends are mixed and assembled with the urban profile of Caracas, the incessant rain, the urgency of scavenging animals, the evil that corrodes, and the signs of decline of a country that could not see what was coming. Juan Carlos Chirinos is a ruthless storyteller. His writing is shown here in all its splendor: raw, unsympathetic, and no less luminous. Anyone who reads Chirinos will not be surprised to recall José Balza, early Vargas Llosa, Céline, Faulkner or Cepeda’s novel La casa grande [The big house]. They are the masters who seem to illuminate this prose.

Los cielos de Curumo [Curumo’s skies] is a narrative arranged as a house of cards in which the lives of five friends are mixed and assembled with the urban profile of Caracas, the incessant rain, the urgency of scavenging animals, the evil that corrodes, and the signs of decline of a country that could not see what was coming. Juan Carlos Chirinos is a ruthless storyteller. His writing is shown here in all its splendor: raw, unsympathetic, and no less luminous. Anyone who reads Chirinos will not be surprised to recall José Balza, early Vargas Llosa, Céline, Faulkner or Cepeda’s novel La casa grande [The big house]. They are the masters who seem to illuminate this prose.

Juan Pablo Villalobos: 10 novelas de César Aira [Ten novels by César Aira]

This volume compiles ten of the best novels by the great Argentine author, César Aira, selected and with a preface by Juan Pablo Villalobos: “Along the way we got used to some only being ten to fifteen pages long; we knew to expect different forms, and to consciously question the rules of what was considered good writing. Because, after all, what can we expect from César Aira’s works? Anything: a clever and unpredictable piece, a miniature narrative that revives and invigorates, again and again, literature.”

This volume compiles ten of the best novels by the great Argentine author, César Aira, selected and with a preface by Juan Pablo Villalobos: “Along the way we got used to some only being ten to fifteen pages long; we knew to expect different forms, and to consciously question the rules of what was considered good writing. Because, after all, what can we expect from César Aira’s works? Anything: a clever and unpredictable piece, a miniature narrative that revives and invigorates, again and again, literature.”

Mayda Bustamante and Gabriela Guerra: Los cuentos que Pessoa no escribió [The stories Pessoa didn’t write]

Fernando Pessoa, a discoverer of the soul and existence, is the greatest Portuguese poet of all time. On the 130th anniversary of his birth, twenty-five women from ten Latin American countries come together to give him a historic tribute. Each of them unraveled one of the many enigmas that surround this immortal poet. This anthology, edited by Mayda Bustamante and Gabriela Guerra, brings together prestigious authors from Spain, Portugal, Argentina, Costa Rica, Mexico, Cuba, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, and Peru.

Fernando Pessoa, a discoverer of the soul and existence, is the greatest Portuguese poet of all time. On the 130th anniversary of his birth, twenty-five women from ten Latin American countries come together to give him a historic tribute. Each of them unraveled one of the many enigmas that surround this immortal poet. This anthology, edited by Mayda Bustamante and Gabriela Guerra, brings together prestigious authors from Spain, Portugal, Argentina, Costa Rica, Mexico, Cuba, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, and Peru.

Patricio Pron: Mañana tendremos otros nombres [Tomorrow we will have other names]

This novel was awarded with the Premio Alfaguara de Novela 2019 [The Alfaguara Novel Prize] and, as the jury said, is “The autopsy of a break-up that reflects the contemporary epoch in an exceptional way.” A work that goes beyond love: it is the sentimental mapping of a neurotic society in which relationships are consumer products. Under the anonymity of some He and She, it builds the story of two characters who are vaguely aware of their own alienation. A subtle and wise text, of great psychological depth, that reflects the contemporary epoch in an exceptional way and takes the pulse of new ways of understanding our feelings.

This novel was awarded with the Premio Alfaguara de Novela 2019 [The Alfaguara Novel Prize] and, as the jury said, is “The autopsy of a break-up that reflects the contemporary epoch in an exceptional way.” A work that goes beyond love: it is the sentimental mapping of a neurotic society in which relationships are consumer products. Under the anonymity of some He and She, it builds the story of two characters who are vaguely aware of their own alienation. A subtle and wise text, of great psychological depth, that reflects the contemporary epoch in an exceptional way and takes the pulse of new ways of understanding our feelings.

Ricardo Piglia: Teoría de la Prosa [Theory of prose]

Teoría de la Prosa compiles nine master classes that Ricardo Piglia taught at Princeton University in 1995. Before his death, Piglia spent his final months reviewing the transcribed material of this book. As a legacy for his community of readers, Teoría de la Prosa is considered invaluable, because it has crystallized all the wisdom and experience of Piglia as a reader and writer. In these classes, Piglia spoke of a myriad of topics that are directly related to literature, and especially the power of Onetti’s writing. As Piglia points out, in “…Onetti´s books, where one enters and leaves real facts for a dimension associated with private fantasy and dream, you never know what has really happened. Onetti aspires that his texts be read only in relation to his own texts, which is extraordinary.”

Teoría de la Prosa compiles nine master classes that Ricardo Piglia taught at Princeton University in 1995. Before his death, Piglia spent his final months reviewing the transcribed material of this book. As a legacy for his community of readers, Teoría de la Prosa is considered invaluable, because it has crystallized all the wisdom and experience of Piglia as a reader and writer. In these classes, Piglia spoke of a myriad of topics that are directly related to literature, and especially the power of Onetti’s writing. As Piglia points out, in “…Onetti´s books, where one enters and leaves real facts for a dimension associated with private fantasy and dream, you never know what has really happened. Onetti aspires that his texts be read only in relation to his own texts, which is extraordinary.”

Ramón Del Castillo: El jardín de los delirios [The garden of delusions]

A critique of the fantasies of hipster naturalism. The “love of nature” inspires all kinds of illusions and desires to escape to green areas, which have taken on a new meaning in an era dominated by ecological dreams and the collective delusions of architectural design. Ramón del Castillo combines different disciplines (psychology, geography, sociology) in an acid vision of the most everyday spaces of evasion, but also of the fantastic scenarios imagined by art, literature, and science. A journey without parallel for the ideas and experiences that have shaped the ideology of naturalism today.

A critique of the fantasies of hipster naturalism. The “love of nature” inspires all kinds of illusions and desires to escape to green areas, which have taken on a new meaning in an era dominated by ecological dreams and the collective delusions of architectural design. Ramón del Castillo combines different disciplines (psychology, geography, sociology) in an acid vision of the most everyday spaces of evasion, but also of the fantastic scenarios imagined by art, literature, and science. A journey without parallel for the ideas and experiences that have shaped the ideology of naturalism today.

Raquel Rivas Rojas: El accidente [The accident]

Olga, a Venezuelan woman who has lived for years in London, returns to Venezuela to bury her sister Carla, whom they have just murdered, during the very week when the death of Hugo Chávez is announced. El accidente tells the story of this return, and of the trip to the province where Carla is going to be buried, through the voices of the witnesses who are accompanying Olga in a journey full of painful discoveries. Raquel Rivas Rojas is a Venezuelan narrator, translator and essayist, who now maintains two blogs: Notas para Eliza [Notes for Eliza] and Cuentos de la Caldera Este [Stories of East Calder].

Olga, a Venezuelan woman who has lived for years in London, returns to Venezuela to bury her sister Carla, whom they have just murdered, during the very week when the death of Hugo Chávez is announced. El accidente tells the story of this return, and of the trip to the province where Carla is going to be buried, through the voices of the witnesses who are accompanying Olga in a journey full of painful discoveries. Raquel Rivas Rojas is a Venezuelan narrator, translator and essayist, who now maintains two blogs: Notas para Eliza [Notes for Eliza] and Cuentos de la Caldera Este [Stories of East Calder].

Ricardo Silva Romero: Cómo perderlo todo [How to lose everything]

Winner of the V Premio Biblioteca de Narrativa Colombiana [5th Colombian Narrative Library Award], this entertaining novel portrays the crisis experienced by different couples in the disastrous year of 2016. As a beginner on Facebook, old professor Pizarro, oblivious to present-day hatreds, publishes a post that puts his life in check. Around his debacle, a tragicomic novel is released in turns. And disastrous 2016—the leap year of the plebiscite for peace, of Brexit, of Trump—becomes a test of nerves for those who fall into their own traps. With intelligence and humor, Ricardo Silva Romero presents this lucid narrative about the dramas of marriage and the absurdities of the relationships we build on social networks.

Winner of the V Premio Biblioteca de Narrativa Colombiana [5th Colombian Narrative Library Award], this entertaining novel portrays the crisis experienced by different couples in the disastrous year of 2016. As a beginner on Facebook, old professor Pizarro, oblivious to present-day hatreds, publishes a post that puts his life in check. Around his debacle, a tragicomic novel is released in turns. And disastrous 2016—the leap year of the plebiscite for peace, of Brexit, of Trump—becomes a test of nerves for those who fall into their own traps. With intelligence and humor, Ricardo Silva Romero presents this lucid narrative about the dramas of marriage and the absurdities of the relationships we build on social networks.

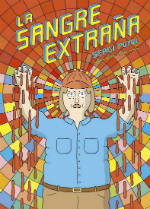

Sergi Puyol: La sangre extraña [The strange blood]

We can escape from anywhere except our head. But what exactly is the “strange blood”? Arnaldo hates Fridays, he hates to work, he hates everything so much, he hates life. But even a nihilist loafer can be seduced by a flash of action and mystery. When a bald gentleman recites an enigmatic phrase in a catatonic trance, his existence becomes a fast-paced and obsessively quixotic search. It will go through Russian novels, hectoliters of beer, daily enigmas, mental totems, and metaphysical doubts because the key is not to know what the strange blood is, but to continue living after having discovered it.

We can escape from anywhere except our head. But what exactly is the “strange blood”? Arnaldo hates Fridays, he hates to work, he hates everything so much, he hates life. But even a nihilist loafer can be seduced by a flash of action and mystery. When a bald gentleman recites an enigmatic phrase in a catatonic trance, his existence becomes a fast-paced and obsessively quixotic search. It will go through Russian novels, hectoliters of beer, daily enigmas, mental totems, and metaphysical doubts because the key is not to know what the strange blood is, but to continue living after having discovered it.

Compiled and translated by Claudia Cavallín