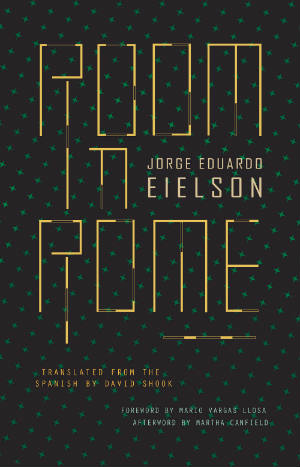

Room in Rome. Jorge Eduardo Eielson. Translated by David Shook. Cardboard House Press, 2019. 102 pages.

Jorge Eduardo Eielson (Lima 1924 – Milan 2006) is a significant name in contemporary Latin American art and literature. He was a prolific and multifaceted author who cultivated, with equal intensity, poetry, the novel, theatre and visual arts. In doing so, Eielson created a rich imaginary that explores the expressive dialogue among these art forms, as well as their integration in his work.

Jorge Eduardo Eielson (Lima 1924 – Milan 2006) is a significant name in contemporary Latin American art and literature. He was a prolific and multifaceted author who cultivated, with equal intensity, poetry, the novel, theatre and visual arts. In doing so, Eielson created a rich imaginary that explores the expressive dialogue among these art forms, as well as their integration in his work.

Eielson was a member of the Peruvian “Generation of 1950” along with other talented writers such as Sebastián Salazar Bondy, Javier Sologuren, Blanca Varela, and Carlos Germán Belli. Thanks to this group, Peruvian poetry abandoned its regionalist bent and entered a period of renovation and innovation. Eielson read the Greek Classics, Spanish Golden Age poets, Rilke, and French surrealists. His work received well-deserved praise beginning with his book of poetry Reinos (1944), published when he was just 21 years old. In Reinos, a restless poetic voice, yet a messenger of exquisitely crafted language, dialogues with the finest voices of the Western tradition while simultaneously grappling to find its own expressivity. In 1948, when Eielson left for Europe, where he would reside the better part of his life, he was already a highly regarded poet in Peruvian literature.

Room in Rome (1954), now appearing in a bilingual edition with David Shook’s magnificent translation in English, a prologue by Mario Vargas Llosa and an epilogue by Martha Canfield, is both a showcase of Eielson’s poetic excellence, and an individual and collective reflection on his exile in Europe. Immersed in the chaos and destruction of the postwar period, Rome is a splendid and miserable place in these poems. The poetic “I” looks for the Eternal City’s former greatness, while also experiencing a growing existential angst triggered by a space that, far from reflecting the values of Classical Antiquity, reveals itself as hostile, almost inhospitable. The poem, “Azul ultramar” [“Overseas Blue”] illustrates as much. The poetic speaker urgently begs an ancient Mediterranean god to return Rome to its former splendor and past role as the cultural and spiritual center of the West: “mediterranean help me/help me overseas/our father who are in the water/of the tyrrhenian/and its twin adriatic/don’t let me live/just as flesh and blood/[…]/make this city that is yours/and nonetheless mine/wake back up/[…]/this city with houses/with restaurants/with automobiles/with factories and cinemas/theatres and cemeteries/and scandalous/illuminated signs/insistently announcing god/with dazzling creatures/made of polychromatic paper/that devour the coldest/coca-cola”.

The poetic voice’s request, however, falls on deaf ears. Rome of the past is now buried under a raucous modern metropolis, a world dominated by “scandalous/illuminated signs” and runaway consumerism. Confronted by this pitiful spectacle, the poetic “I” discovers that living in Rome means existing in a base, animal-like state, one dominated by material and physical necessities and overwhelming loneliness.

For several reasons, Room in Rome can be read as a chronicle of one’s alienation living in a modern city. Its texts fuse personal and collective stories, repeatedly demanding a more familiar rapport among those living in the Eternal City, thus explaining the repeated use of the vocative throughout the book. Additionally, a colloquial manner of speaking, yet one with a symbolist and surrealist air, shines through in the work. This voice contemplates Roman monuments’ ancient beauty and cultivates a lucid, reiterative musicality in many verses. In a word, Room in Rome is as confessional as it is grim, capable of emotively expressing such human experiences as indifference and solitude.

In this context, the poetic “I” soon becomes the victim of a sense of alienation and existential distress, expressed in the poem “Via Veneto” with the following: “I ask myself/if I truly/have hands/if I truly possess/a head and two feet/and not just gloves/and shoes and a hat/and why I feel/so pure/even purer still/and closer to death/when I remove my gloves/my hat and my shoes/as if removing my hands/my head and my feet”.

The poetic voice’s alienation is taken to the limit in “Poem to Read While Standing on the Bus Between the Flaminia Stop and Tritone.” At the end of the poem, the speaker conveys an existential nihilism, or, in other words, a negation of love and the surrounding material world, as well as the abandonment of the poetic word itself. The poetic “I” announces: “it’s useless to always be/writing about oneself/or what one doesn’t have/or just what one remembers/or just what one desires/I have nothing/I repeat nothing/ nothing to offer you/nothing good no doubt/nor anything bad either/nothing in my gaze/ nothing in my throat/nothing between my arms/nothing in my pockets/nor in my mind/but my heart ringing high high/among the clouds/like the boom of a cannon”.

Martha Canfield astutely writes that Room in Rome is the chronicle of “a tireless pilgrim on the streets of the Eternal City, [seeking] something he knows he cannot find, thus embodying the distressing bewilderment of our age”. Once Eternal Rome is demythified, we find a subject who “[battles] poverty, loneliness, and isolation, but most of all the masks imposed by society, which destroy the integrity of the body,” or that which Eielson believes constitutes “the vehicle and form of the soul”. In effect, a desire for spiritual transcendence, along the lines of the Spanish mystics, is also a recurrent motif throughout Eielson’s work.

This bilingual edition of Room in Rome is certainly one we should celebrate, not only because it puts Eielson’s poetry into the hands of new readers, but also because the artistic quality of this book makes for a spectacular entry into the creative universe of a true artist who left behind a rich, expressive and multifaceted life’s work.

César Ferreira

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Translated by Amy Olen

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Amy Olen is an Assistant Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She finished her Ph.D. in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at The University of Texas at Austin on Guatemalan Maya-Kaqchikel author Luis de Lión. Amy holds Master’s Degrees in Translation Studies (2006) and Spanish and Portuguese (2010) both from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Her research interests include Central American and Andean Indigenous writing, and Translation Studies.