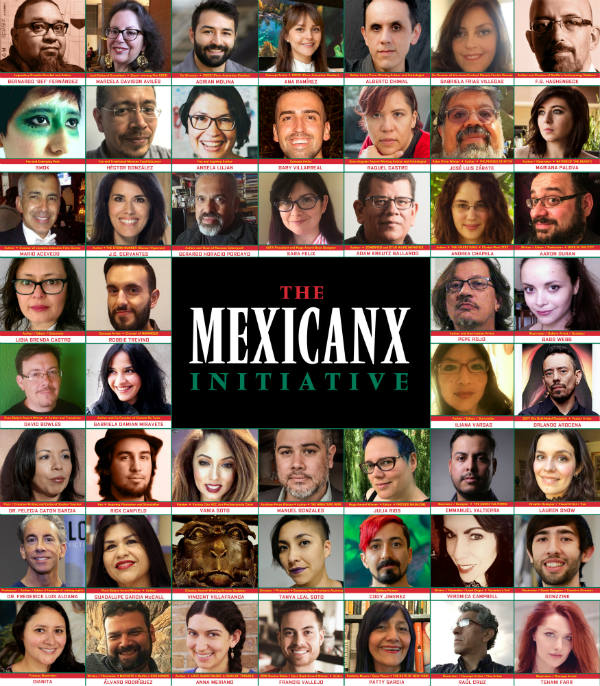

The Mexicanx Initiative, comprised of around 50 writers and authors of science fiction, fantasy and horror, attended The 76th World Science Fiction Convention in San José this summer. Stephen Tobin chronicles his experience there and the importance of the initiative.

We will remember 2018 as the year Mexicanx Science Fiction1 finally got the recognition it deserves. One core reason for this was the appearance of The Mexicanx Initiative at this year’s World Science Fiction Convention, aka WorldCon, located in San José, California during mid-August. Now in its 76th year, the convention boasted many thousands of attendees over a five-day stretch, which included hundreds of events comprised of panels, talks, readings, discussion groups, autograph signings, concerts and dances that cover as ample a spectrum as could be imagined,2 all culminating in the coveted Hugo Awards on the event’s penultimate night. For the uninitiated, it might be helpful to think of WorldCon as Comic-Con’s older, poorer, less sexy, less popular yet more promiscuous sibling, since it has been around since 1939, takes in a fraction of money, does not attract the glamorous A-list Hollywood celebrities to its panels that the annual San Diego spectacle does, draws more than a third fewer of its attendees on average, and moves from city to city each year. But whatever WorldCon may lack in these areas of an imaginary competition, it excels in fervor and fandom.

WorldCon exalts fandom and nerd culture with such palpable pride that Oscar Wao would have unnoticeably blended into the backdrop, and might have even attended the panel “Representation in Geek Media” or the talk “Geeks Guide to Literary Theory.” Fandom reaches such an apex here that during the opening ceremony, the chair of the event Kevin Roche even proudly stated: “WorldCon is the World’s Fair of fandom.” Toward the end of the convention, the Hugo Awards MC gleefully declared that fans are so important they even have award categories for them, i.e., Best Fan Artist, Best Fan Writer, Best Fancast, Best Fanzine. Even the first person I conversed with at the whole event said, after telling him I had never attended a WorldCon in the past, that “this is not like other genre conventions—here we are very participative. Here, you’re a member.” And by member, he not only meant that they are a close-knit part of a community that happen to be spirited and garrulous during the Q&A section at panels, but they also pay membership dues, which in this case are the actual entrance fees to the convention. $250 was the adult price tag to attend all five days of events.

This fans-members-dues link connects to what science fiction made in Mexico wholly lacks: a market. (The reasons for this are complex and beyond the scope of the space provided here, but involve an oligarchic publishing industry, an inane distribution and display policy of authors’ works that results in inefficient and ineffective promotion, and a conservative and largely patriarchal literary establishment that aids in perpetuating the stigmatization of the genre as a non-serious, para-literature.) This may seem obvious to any Mexican or Latin American reader, but it bears repeating and emphasizing for anyone unfamiliar with how the publishing industry of this genre works in Mexico. Walk into any chain bookstore in the country and you will be lucky to find any Science Fiction/Fantasy sections. If they do carry any titles, they will most certainly be the translated classics from the sci-fi ABCs (Asimov, Bradbury, and Clarke) and a slew of bestsellers from the Global North, a large number of which pertain to the (relatively new) niche subgenre carrying the Young Adult label, e.g. Hunger Games, Ready Player One. No market means little-to-no monetary support for the livelihood of those who create the narratives, and no writer comes close to making a living at their work.

But to call the production of science fiction in Mexico a labor of love both understates the conditions under which the authors continue to produce their work and romanticizes their quotidian reality. Maybe the more apt description comes from author Gabriela Damián when she observed during a panel that “science fiction made in Mexico is a huge cockroach that endures a devastating catastrophe, like a nuclear bomb. Publishing-wise, we have survived.” Not only have they survived a publishing milieu that is either indifferent or disdainful to producing and promoting their work, but they have arguably flourished despite this; their presence at WorldCon underscores this claim. In distinct contrast, the chicanx contingent of The Mexicanx Initiative has access to one of the strongest markets of readers and fans on the planet, but their production has been traditionally –and sorely– underrepresented within the industry that the convention contains. The Mexicanx Initiative aimed to reverse both these states of affairs by giving the participants some visibility and promotion.

The Initiative sprang forth from the seedling of an idea by one of this year’s WorldCon76 Guest of Honor, illustrator John Picacio. In the past he has twice won a Hugo Award—the crown jewel of science fiction awards—and was also invited to be this year’s Master of Ceremonies for the Hugos. His being Mexican-American led him to discover that no Guest of Honor or Hugo Award MC had ever been a brown person. “I thought it’s great to be the first,” he said, “but who cares if you’re the last? That’s the question I kept thinking about: who would come behind me? I break the door down, but then who’s coming through the door after me?” Initially, he thought he would sponsor one or two people (i.e., pay for their membership fees) out of his own pocket, but then his friend and novelist John Scalzi said he would do the same. Shortly after, more people agreed to sponsor, and before long, when the number reached 10 people, the whole process gained the momentum of a sizable snowball just picking up speed down a mountain. At that moment, Picacio decided to aim for sponsoring 50 people and gave the project its official title of The Mexicanx Initiative. By convention time, approximately 15 Mexicanx nationals along with 35 Mexicanx-Americans held sponsorships. (A similar origin story lies behind the bilingual anthology A Larger Reality: Speculative Fiction from the Bicultural Margins, which was published just for the Initiative at WorldCon76 and receives an in-depth treatment in the prologue to the dossier.) Ultimately, Picacio said, this was not just merely some brown people getting together but “this was a human endeavor, like George R.R. Martin said [at the Hugo Awards after party]. It was all cultures getting together to bring in another that wasn’t really being included.”

If inclusion was a pretext for the industry in which the Mexicanx Initiative arose at WorldCon76, then exclusion was —and still very much is—the socio-political context in which Mexicans and Mexican-Americans live and breathe in the US. The shift toward authoritarian nationalism has opened a Pandora’s box of racism and xenophobia that has helped fuel a strategy of scapegoating brown people for America’s vastly complex problems. As a result, Mexicans and Chicanos that now live here in heightened apprehension and perpetual fear. In the past year and half the real effects have been legion: i) ending the Dream Act, ii) letting DACA expire, iii) increased deportations for non-felons (contrary to the rhetoric stated as to the original motivation), iv) criminalizing asylum seekers from Mexico and Central America who cross the border, v) separating immigrant parents from children (as of this writing, 500 children remain orphaned and the number of detained children has gone from several thousand in May 2017 to an historic high of almost 13,000 as of the beginning of September). Directives and policy chances made from above have trickled down to the populace, resulting in numerous attacks on people simply speaking Spanish in public. One of the most disturbing examples must be this 91-year old Mexican man beaten with a brick in Los Angeles during an evening walk and told to go back to Mexico. “Even if you’re a legal Mexican-American like me,” Picacio said, “you’re not safe right now.” This is not hyperbole: less than a week after saying this, the Washington Post revealed the US’s denial of passports to some Mexican-American citizens along the border, throwing their citizenship status into legal limbo. This invective even showed up at WorldCon76 when an alt-right rally convened on the second day of the convention.3 Even though the protest resulted in a tepid fizzle of around 20 participants, it is hard not see this as ethno-nationalist fascism knocking on the front doors of the San José Convention Center, trying to get in.

In protest of this toxic environment, all the attending participants of the Initiative took to the stage for the opening ceremony while Picacio read a politically charged statement (viewable here) and each participant connected as brothers and sisters in arms. There were rumors that three Mexicanx —Bernardo Fernández, Gabriela Villegas, and H. G. Hagenbeck—cancelled their trip in protest to this climate and the separation of parents from children at the border. Numerous other nationals were unsure about crossing the border for WorldCon76. In the end, however, the majority of the 15 arrived. Editor and author Libia Brenda insisted that just her presence at WorldCon76—and all that it took to be there—was her own form of protest to the current situation.

Turning to the artists and writers of The Mexicanx Initiative itself, it quickly becomes an exercise in frustration trying to delineate any aesthetic tendency within the group; there are simply too many factors to consider them as a single inclination. The group of Mexican nationals, besides not having a market to truly support their work, encompass a vast expanse of writing styles (and only one visual artist). The chicanx were comprised of an impressive mixture of writers, screenwriters, poets, film directors, visual artists, concept artists, vector artists, 3D artists, sculptors, graphic designers, editors, painters, professors, musicians, and fans. Together, they comprised 70% of the Initiative, with around 15 writers and the rest forming part of this ample creative collective. The only trait these two groups share is the identity marker of being from Mexico or of Mexican descent, and even this holds varying degrees of importance in their creative output.

In the work produced by those in The Mexicanx Initiative, the issue of cultural heritage reveals the following broad distinction: for many Chicanxs, Mexico’s rich cultural history—replete with pre-Hispanic myths and figures, iconic places, and urban/rural legends—tends to be a salient feature of their work; for those cultural producers of the genre from Mexico, these elements are at best peripheral, if not altogether absent. From the Mexicanx-American side, one emblematic case is David Bowles, whose entire book Chupacabra Vengeance delves deep into the many shades of this folkloric creature (see his story in the dossier). Another example is author Mario Acevedo, whose seven-part novel series that follows the protagonist vampire-detective named Felix Gomez has as the latest installment, Steampunk Banditos, set in Aztlán. Both these writers follow in the tradition established by pioneering chicano author Ernest Hogan. In the visual arts, John Picacio’s own Lotería series, which reimagines the traditional Mexican card game similar to Bingo, includes well-worn icons like El Nopal and La Calavera, impressively detailed in sci-fi and fantasy garb. (For those within this segment that forego this tendency, their narrative thematics lean toward highlighting social and subjective marginalization in their characters, assumedly akin to their own experiences as chicanxs in the US. This is clear from Julia Ríos’s “A Universally Recognized Truth” or Felecia Caton García’s “Matachín,” an excerpt from her novel; both are available in the link provided in the prologue.)

However, those who write from Mexico tend to do so without recurring to these kinds of icons as integral aspects of their fantastic universes. Pepe Rojo explains, for example, that his experience with computers affect him as much as they affect anyone who lives in the world’s industrial centers: “We share this reality. This is a dialogue…without needing to romanticize Aztlán or La Llorona. That is a given and been overdone for us.” Rojo sees himself in a conversation that is global in its reach. This is not to say Mexico as an imagined place does not exist in their work, but rather it is the re-imagined Mexico of today or tomorrow, not the past. They take as their starting point the contemporary experiences within their lives and then imagine and extrapolate from there. As Iliana Vargas points out, “for those of us who live in Mexico City, just walking out onto the street is almost a science fiction story. It’s an adventure to just leave your house and everything you have to do to get from one place to another.” This lack of exoticizing Mexico remains true if you read the bulk of the work by national authors José Luis Zárate, Libia Brenda, Gerardo Porcayo, Gabriela Miravete, Alberto Chimal, and Raquel Castro, among others. They are preoccupied with their here and now and presumably will be well into the future.

The only other significant commonality between the two parts that make up The Mexicanx Initiative is that no artist or writer from either group was aware of any other individual’s work in the other. They were totally unaware of each other. This was even true for some within each of the two segments. If we consider how marginalization becomes a central aspect to their identities and/or their work, maybe this is not that surprising. But given that this is a grouping of people who identify strongly with Mexico and all create fantastic literature or art to one varying degree or another, one would think they might be a little more aware of each other’s presence. What is clear, however, is that the Initiative will likely reverse this phenomenon going forward.

On day three of the convention, I happed upon some participants from the Initiative sitting around a circular table. I initially wanted to enter the conversation but then decided against awkwardly interrupting and trying to insert myself into their sphere. Instead, I sat nearby and listened casually to the discussion. My count showed half were Mexicanx and the other half Chicanx – a representative cross-section of the entire Initiative. They talked freely back and forth, exchanging perspectives about being on panels and navigating the frenetic pace of WorldCon. Laughter peppered the conversation. If you had been there, you would have sworn you were witnessing the creation of community in action—the building of bridges that promised future collaborations and enduring friendships. Later, this scene reminded me of an excellent photograph taken early during the event where many members of the Initiative are walking toward the camera with John Picacio heading the group. An effusive smile spans his face, which is clearly contagious because everyone else in the group projects a similar expression of excitement and accomplishment. They are walking individually—but also collectively—toward a common destination, which invariably includes the future. Here, for some moments in the summer of 2018, they are together, visible, recognizing each other, and appreciating getting some long-overdue recognition from the greater world of science fiction. Let’s hope this is a sign of things to come.

1 I am consciously employing the term “Science Fiction” in order to follow the same generalist spirit that WorldCon does by continuing to call itself The World Science Fiction Convention despite rather liberally incorporating adjacent non-realist genres of fantasy and horror (among others) under the term’s purview. They do this for reasons connected with the historical development of the genre, its industry and this particular convention, all of which is beyond the scope of this chronicle to explore. However, it is important to note up front that science fiction clearly reigned as the dominant genre throughout the convention. Also, by using the term “Mexicanx” the widest possible semantic net is cast, including people from the country of Mexico and those of Mexican descent that grew up living outside, such as in the US or Canada, as well as the myriad of self-identifying gender positions available to all writers of this genre.

2 Panels ranged from the more boilerplate sci-fi offerings of “Utopia to Dystopia (and Back Again)” and “Science: The Core of SF’s Sense of Wonder” to the niche and expansive, such as “Self-publishing 101” and the inclusive “Prounouns Matter: Gender Courtesy for Fans.” The variety of talks and readings spanned from “Our Once and Future Bodies” and “911 in Freefall: Handling Medical Emergencies in Space” to the more standard academic offerings of scholars presenting their analyses of important authors like Philip K. Dick or a subgenre, like Afrofuturism. Readings enjoyed an ample variety, from poetry readings, to authors like Corey Doctorow reading excerpts from their own work, as well as two separate sessions for the Mexicanx Initiative: one in English and the other in Spanish. Saturday’s Steampunk Ball, as might have been expected, hosted around 100 people, many of which were dressed in the distinctive dress style inspired by re-imagined 19th century attire. Autograph signings occurred throughout, with George R. R. Martin being the biggest name, as well as the Mexicanx Initiative’s founder John Picacio.

3 This event was organized by Jon del Arroz, who is a staunchly conservative and self-described “Leading Hispanic Voice in Science Fiction” (according to his website). Del Arroz’s backstory includes initiating a lawsuit against WorldCon76 for denying him entry (for openly stating he would violate their rules of filming people without their permission) and, spearheading a counter-point to Picacio’s Mexicanx Initiative called “The White Male Initiative for WorldCon76,” which apparently never materialized beyond a short-lived crowdfunding campaign. Or maybe it did—in some way—work? The average attendee was a white male between the age of 40 to 60 years old.