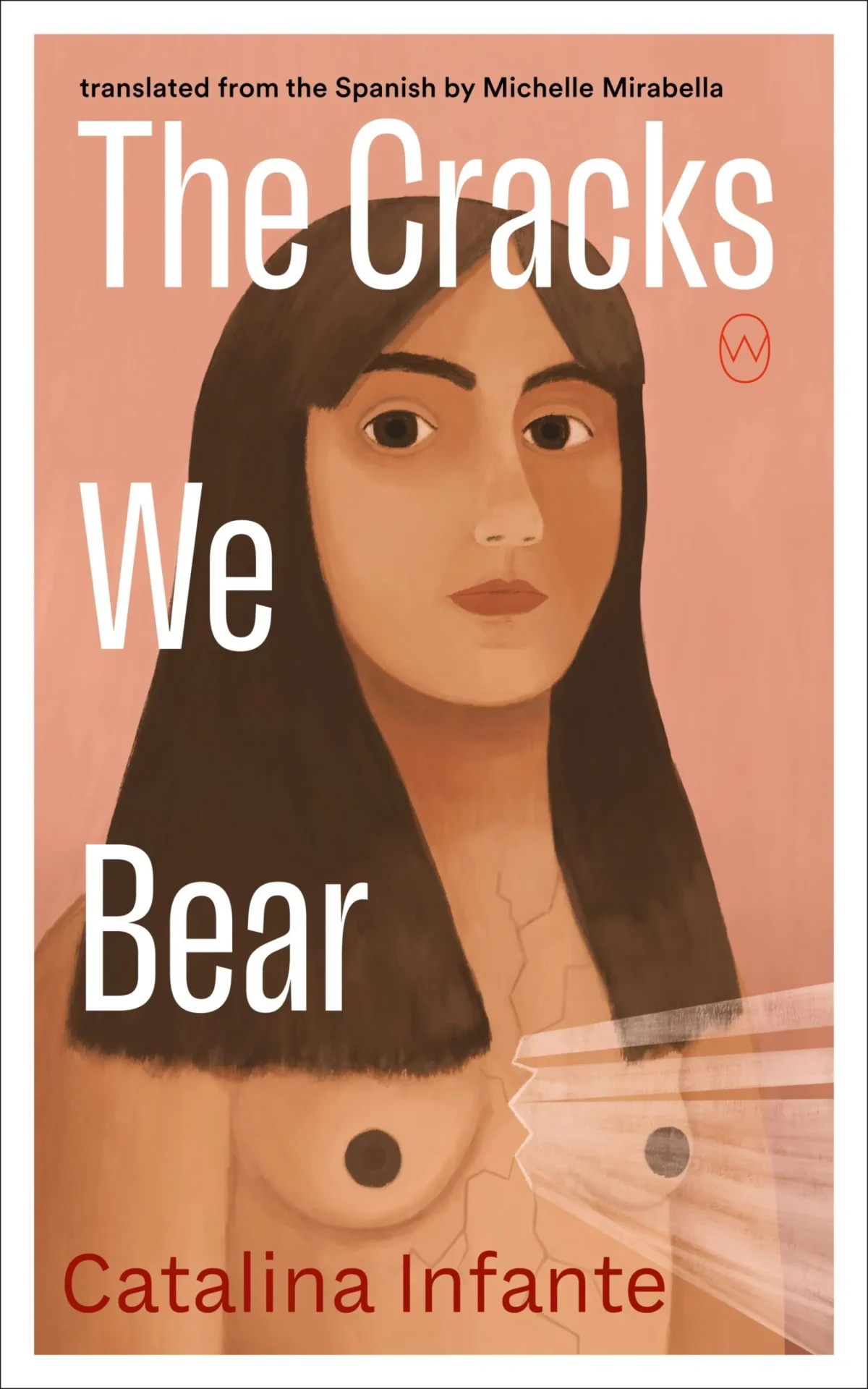

Following over five years of collaboration between writer Catalina Infante and translator Michelle Mirabella, which began with the translation of the story “Ferns,” published in World Literature Today, Infante’s 2023 novel La grieta, now The Cracks We Bear, is out from World Editions in Mirabella’s translation. What follows is a conversation between Infante and Mirabella about the unique bond between writer and translator and this literary milestone of their English-language book-length debut.

Michelle Mirabella: “Perhaps there’s a word for it in another language, a grouping of letters whose sound can hold such emptiness.” Reading that sentence in the first chapter of your debut novel, La grieta, led me to think about how the act of writing is a way of translating the self. What has it been like to see yourself translated twice: first in your own words and then in mine?

Catalina Infante: I was actually just invited to participate in a panel alongside other Chilean women authors called “Writing the Emptiness,” and I was left thinking about that idea or question. I think the initial seed for writing this novel is precisely the quote you shared: how can I find a way to write about the emptiness left by the death of a mother? How can I find a way to write about the grief women go through during postpartum or “puerperium.” And the most difficult: how can I find a way to connect those two emotions? I had to write an entire fictional work to even get close to an idea of a definition. In that way I translated myself; I put into words something I felt running through me. Now that I think about it, I passed the baton to you so you could continue down that path… To answer your question: writing this novel was wonderful for me; I was able to recount and explain to myself many things from my own story that I hadn’t resolved. What was it like for you to read and translate this novel, considering how it also coincided with your own motherhood?

M.M.: The novel accompanied me throughout the entire process of becoming a mother, the highs and lows, and I felt like we shared a certain mutual understanding, the novel and I: the novel gave me insight into new motherhood while my new motherhood left its mark on my translation of the work. When I read it for the first time my body had never been pregnant before, so I spent that first reading reflecting on how I would approach translating a first-time mother’s body and state of mind. I did my research and asked questions to understand the both physical and emotional transition beyond your words on the page. I recall texting my friends questions such as “when your breasts are full of milk, give me adjectives to describe the sensation.” And when my daughter arrived, I had the opportunity to reread the novel and revise the translation from my new body and state of mind and leave something of my own motherhood in its English-language version. Throughout my revision process I always send you questions, and I feel we’ve come to trust one another greatly. What has the experience been for you, in these five years of collaboration and friendship, to entrust your work to another?

C.I.: It’s been an unparalleled literary experience. I feel so fortunate to be able to have this experience, because I think, just as there is a very unique bond between author and editor, the same is true of the author and translator. I feel like you’re a coauthor of my book in English. Just recently I sent the translation of my story “Ferns” to a friend who speaks English. He’d read the Spanish-language version first, and when he read it in English, he told me he felt it had gained something, that, for example, the words Husband, Son, and Mother (the characters in the story) carried more weight than in Spanish. Knowing my literature could transform in that way, adding meaning to words or giving them new intentions gave me vertigo, and I liked that. Translation comes with a certain loss of control because language reflects culture, and inevitably what I originally wrote will adapt organically to that other culture. And that gives the text a new life. So, you have to trust in your translator to give them that freedom, and I think that’s something that’s developed organically between us, in a magical way. And since we met, so many years ago now, I feel like I’ve been able to trust you with my writing (without knowing much English myself), because I sense that we have a similar outlook on life or a shared sensibility. Which makes me wonder: what makes you want to translate a work, or what is your criteria for choosing a specific work?

M.M.: When I’m the one choosing, I’m looking to feel a connection with the work, to see something special in it, but I’m also looking for the possibilities that could arise. To date I’ve always read the entire work before making a decision because the texts I choose, and perhaps even more importantly my approach to them, are a reflection of my criteria and, in a way, my values. And translating a work is almost always a long-term commitment; you have to believe not just in the work itself but in the team you can create with the work and/or its author. As an example of this commitment and the possibilities I’m talking about, the first work of yours that I read was Todas somos una misma sombra [We women are all one shadow] in February 2020, and after all these years and various publications of ours it’s still there waiting, fully translated, without a publisher (but with hope!). And the connection I felt with that book, and then with you when I wrote to you, opened up a world of possibilities for me. It led me to have this truly beautiful collaboration with you in which I have the opportunity to create harmony in the translation of your work as a whole, its themes and threads. On the topic of themes and threads, regardless of the language in which it’s written, what defines your work?

C.I.: It’s so hard to describe your own literature because it’s born from such an unconscious place that sometimes you don’t know where it’s going; it just exists. The readers are the ones who come along later to complete the puzzle or offer you unexpected information in return. I do think writers are on journeys searching for something specific; we have obsessions that haunt us, as if we were searching in literature for the answer to something. Lately I’ve been reading Han Kang and revisiting some of her books, which have accompanied me as I write the novel I’m working on now. I feel very represented by her search—or the one I perceive as a reader, which is always subjective—which always involves the body. Her women characters are silent, complex, dark, damaged; they seek an escape, redemption, and the answer is always to leave the body itself, to become ethereal. Han Kang is much more than what I describe here, but what really resonates with me are these women from The Vegetarian, Greek Lessons and We Do Not Part1 who carry a deep crack and embark on a personal journey to try and heal, through starvation, the loss of language, or a journey to a phantasmal island. In light of this, I’ve also thought about what I’m searching for and feel like it’s not far off from that. In a way the protagonist in The Cracks We Bear embarks on the journey of motherhood, through a body that changes, as a way of understanding and healing a fissure with her mother that she’s been carrying since she was a girl.

M.M.: Yes, that’s a common thread I see in your work, the body, going back to my first reading of Todas somos una misma sombra to some of your essays and obviously The Cracks We Bear. And you go beyond just the body and its transmutations, you connect it to an emotional or psychological journey that sometimes blurs for us—us being your readers—the concept of time, bringing sensation to the foreground. And as the translator of your work, it has been such a beautiful process to find the way to express the sensations you write, the consistencies in your texts, their possibilities… and I’m really excited to continue that work when the time comes to read the new novel you mention. But getting back to The Cracks We Bear, if you could share a reflection about the work with your readers, what would you tell us?

C.I.: You’re putting me on the spot again, haha. I’d say, on the most intimate level of the creative process, the novel represented a personal journey that accompanied me through my own motherhood and unresolved grief. I share much of my own story with the protagonist: motherhood, exile, and grief. Although the story in which I reflected those unsettled feelings is far removed from mine, I’d like to share with readers that the novel holds a personal search for understanding and repairing a crack, and I hope they feel that honesty through Laura and Esther.

M.M.: I certainly felt that honesty, and it continues to accompany me in my own journey through life. And in addition to the novel’s honesty, which drew me in, I see within it fragmentation that connects with the fact that trauma can affect memory. I see fragmentation in the novel’s form, its vignettes, “the simultaneity of all the presents” and that duality of time: past and present. For me the novel becomes a cracked and reconstructed jug, taking the form of the relationships full of cracks you write about in chapter eleven. How did you come to give this fragmented form to the novel?

C.I.: It came naturally to me. In fact, one of my current challenges as an author is to be able to depart a bit from fragmentation and sustain a longer narration. I have ADD and I have trouble concentrating for a long time on something. In a way my writing is like this because I am like this; my mind functions in a fragmented way, in capsules of time, and writing is ultimately an extension of the self. It’s much easier for me to write poetry or short stories; the novel undoubtedly presented a major challenge for me, and look how it turned out: extremely fragmented. But it worked because the story itself called for that format; Laura is living through a period of time with constant interruptions because of motherhood. What postpartum mother can focus on something for more than twenty minutes? The demands of a baby are constant and that’s the rhythm that moves through the novel. Apart from that, Laura and Esther have a broken bond, and when something breaks it leaves fragments behind. Laura searches in her memory for the pieces she has and goes about putting them together to see the full picture; a picture that, as it turns out, will never be complete. Wrapping up my answer now, what expectations do you have for how The Cracks We Bear will be received in its English-language version?

M.M.: Beyond responding to the lack of Chilean literature on the shelves of English-language readers, the novel redirects the focus of new motherhood, and I think that shift of focus differentiates it from other fiction or creative nonfiction about motherhood—it explores the mother-daughter relationship, but with an emphasis on that of the new mother with her own mother. It’s an intergenerational reflection about the complex relationship that lies at the heart of our identity development as mothers, regardless of the language we speak. And the readers, be they mothers, daughters, or their loved ones, will respond, I think, to the threads of joy and grief that form the fabric of the novel and life itself.