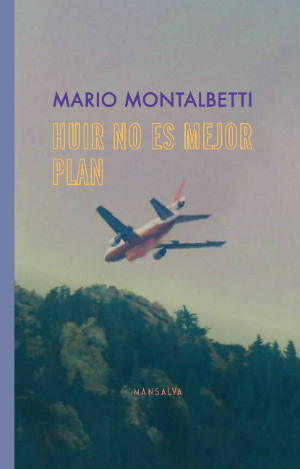

Huir no es mejor plan. Mario Montalbetti. Selected by Gerardo Jorge. Buenos Aires: Mansalva. 2017. 144 pages.

A couple of years ago, Mario Montalbetti offered a poetry reading in Buenos Aires, at the La Internacional Argentina bookstore, managed by Francisco Garamona and Nicolás Moguilevsky, the headquarters of the mythical Editorial Mansalva. They presented Montalbetti that evening, and Gerardo Jorge accepted the mission of saying a few words before the guest opened his selection of poems; the Peruvian poet’s gray hair and glasses didn’t presage the currentness of his proposal, his corrosive irony and his way of problematizing language. For many attendees, that evening was like a glass of cold beer; the freshness of that scene remains intact in the anthology Huir no es mejor plan [Running away is not the best plan].

A couple of years ago, Mario Montalbetti offered a poetry reading in Buenos Aires, at the La Internacional Argentina bookstore, managed by Francisco Garamona and Nicolás Moguilevsky, the headquarters of the mythical Editorial Mansalva. They presented Montalbetti that evening, and Gerardo Jorge accepted the mission of saying a few words before the guest opened his selection of poems; the Peruvian poet’s gray hair and glasses didn’t presage the currentness of his proposal, his corrosive irony and his way of problematizing language. For many attendees, that evening was like a glass of cold beer; the freshness of that scene remains intact in the anthology Huir no es mejor plan [Running away is not the best plan].

Gerardo Jorge’s selection of Mario Montalbetti’s work consists of a survey of eight books, which go from 1978’s Perro Negro: 31 poemas [Black dog: 31 poems] to 2016’s Simio meditando (ante una lata oxidada de aceite de oliva) [Ape meditating (in front of a rusty can of olive oil)]. Along with this sample, and as an epilogue, is an interview between the two—the selected and the selector—in which nothing is wasted: like Humboldt’s penguins, the poet migrates across the entire Latin American tradition to give a panoramic vision of the currents and coastlines on which his proposal is based.

That said, it’s possible that this burst of publications of his books throughout the continent and even in Spain comes at a moment when poetry is passing through a state that is, if not critical, at least singular. Seemingly, the emergence of new technologies and the editorial boom of certain phenomena that seethe around us take for granted that the tone of poetry should be entirely lyrical and separated from its time and place of enunciation. Poetry, in such cases, is empty of any problematic emerging from its field of action, on the level of confronting the discourses that define what is real and what isn’t: they create an experience anchored to the past and a reader who knows what he’s looking for.

On his part, Montalbetti offers another angle, if not many, in which writing puts its possibilities under injunction, not without adopting that hint of black humor that characterized other precedents like Antonio Cisneros, Nicanor Parra, and Enrique Lihn. For example, his “Poema en Homenaje al V Congreso Nacional de Filosofía del Lenguaje, Huampaní 26-28 de junio del 2010” [Poem in homage to the Fifth National Conference of the Philosophy of Language, Huampani 26-28 June 2010] opens with the question: “¿cuál es la diferencia entre una vaca y el lenguaje?” [what’s the difference between a cow and language?]. Well, according to the poet, the cow:

Pace al lado del camino

El camino da un rodeo

Y lleva hasta el granero

La vaca cruza el camino

Sin rodeos

El lenguaje no puede hacer eso.

[Grazes beside the path

That path takes a detour

And reaches the barn

The cow crosses the path

Without detours

Language can’t do that.]

He seems to be saying that, in poetry, we must take nothing for granted, much less its materials: an affirmation that not only frames Montalbetti in that line, so well developed in the latter half of the twentieth century, that line of distrust that also allows him to search in different waters, of different consistencies and temperatures: the poem passes by the essay, it passes by discourse prepared for an unknown audience, and at the same time it establishes itself through logical mechanisms that allow for the scientific confirmation of any sentence. This pirouette, which is also the pirouette of irony, confers to the text the ability to disarticulate something that seems untouched these days: knowledge and, therefore, information.

Perhaps we ought to think of Mario Montalbetti as that student who’s always sitting in the back of the classroom asking uncomfortable questions, or who points out, in the midst of the professor’s enthusiasm, that there’s an error in his explanation. He also reminds us of that character from the novel Birthday by César Aira, who discovers, about to turn fifty, that an idea he has believed in his whole life about the phases of the moon was completely mistaken, until, at one moment, he confesses: “I see it all as an illusion, a simulacrum made of words.” And that’s where his poetics come into play, in the dismantling of an assemblage, which is the basis of his great 2012 book Apolo Cupisnique, perhaps the one that best condenses his work, with a poem like “Biografía” [Biography]:

Me busqué a mí mismo

Y me hallé a mí mismo

Y me hallé a mí mismo, sonso.

Elogié una sola cosa a cambio de todo

Y luego negué caminando bajo palmeras.

Llegué a la inevitable certidumbre de que el devenir

Me alcanzaba en olas serias.

Nada es. Tal vez el fuego es. Busqué leyes.

[I searched for myself

And I found myself

And I found myself, stupid.

I praised one thing in exchange for all else

And then I denied walking under palm trees.

I reached the inevitable certainty that changing time

Would reach me in serious waves.

Nothing is. Maybe fire is. I searched for laws.]

The end of this verse relates again to Aira’s character, who at one point confesses to not knowing anything, saying “I only know I don’t know everything. And I don’t even know that with conviction, I just find out by accident, by stumbling in.” This leads to that argument that Montalbetti’s poetry is often “cold,” “calculated.” This is true, in a sense, if we see in this project of trial and error a highly scientific element, with the poem as an experimental field. But, at the same time, yes and no, since these measurements and tests are registered by an I that doubts, that often possesses a heavy emotional weight and, above all, a voice that wraps it up in a feeling of estrangement, of being outside, of asking “why are there Peruvians instead of no Peruvians?” or, from his first books, pointing out empty houses, towns that appear out of nowhere, lonely places, “five minutes of horizon,” until he tells himself: “I am not from here.” As if the poet and the poem had another sense of belonging that is neither sedentary nor nomadic.

It’s possible that, at this point in the review, some readers would insist on my mentioning the influence of Montalbett’s work as a professor of linguistics in different American universities, and those readers wouldn’t be wrong. The poet says it himself in the interview from the epilogue:

“I’m still a linguist, and I teach linguistics at the university. And that ambiguous or mistaken relationship with language, from a double angle, has continued up to now. And I think it’s that formal, linguistic part that sometimes places me on the margin of what’s really happening in Peru.”

And it’s possible that this relation with the word is what defines the true place of this writing, that is, in the proceedings of speech, his rootedness in language; this has also allowed for the current reception of his writing in Latin America, creating, at every visit and reading, an audience curious to hear his mechanical instruments and his evasion maneuvers. The selection of Huir no es mejor plan works as a one-way ticket toward those areas, to those experiences of language that are “part deceit, part hope, part truth.”

Diego Alfaro

Translated by Arthur Dixon