Editor’s Note: In this section, we share texts originally published by our parent publication, World Literature Today (WLT), now in bilingual edition. This text was first published in World Literature Today Vol. 95, Nro. 1 en invierno de 2021.

Click here to subscribe to WLT:

During the Neustadt Prize ceremony on October 21, 2020, David Bellos read the English-language version of Kadare’s prize lecture to a worldwide Zoom audience.

I am happy and honored that the ceremony organized in honor of my being awarded the Neustadt Prize coincides with the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the prize.

There is no shortage of questions about literature. We hear questions such as, Does the world need literature? This question would call to mind clichéd TV-show questions, trying to stir up debate, had it not been already raised thousands of years ago. There have obviously been two parties lobbying over this question, for and against literature.

Literature was born along with a denial, a barrier. Even if at first this seems strange, if we think about the questions, we will reach the conclusion that this negation is somehow befitting of literature, and it is even quite natural. Literature and negation are one and the same. Rather than being born of angels, literature is the handiwork of demons.

Let’s look at things more simply. Literature, in the form of early oral poetry, has often had as its subject matter the return from long travels: telling of what happened there, at the far border of a country, the desert, or death itself. The first travelers coming from afar were practically the first writers. Walking back to their countries, in the solitude of the road, their minds reconstructed events in such a way that they would be most interesting to listeners. Thus, along the way, dialogues emerged, events became more exciting, colors grew brighter, and something was emphasized while something else erased.

Although the travelers brought with them stories, their heroes stayed mostly far away. They were absent, always from beyond, either on the other side of state lines or on the other side of life—meaning they were dead. In this way, since its beginnings, death and absence assumed a special place in literature. But literature entered death’s domain not to curry favor, but as an equal. In the majestic Epic of Gilgamesh, literature, fully knowing the power of death, still assumes the right to censor it. Gilgamesh is defeated by death, but for the sake of literature, part of him still escapes the grip of death. In other words, using contemporary verbiage, we might call this a contract. Only great art could engage in such contracts with the impossible. Literature continued to feed off of death and its subsidiaries: nighttime, sleep, dreams, guilt.

From its very beginnings, literature was bound up with sacrifice. Troy was the first victim on its altar. Subsequently, there were hundreds of events, subjects, characters, and scenes drenched in blood and grief that fed the literary repertoire. When the Albanian poet Fan Noli translated Victor Hugo’s Waterloo, he noted at the end that after all the tragedy between the pages, he had a single consolation, that he himself was alive, and the poem had been reborn through him.

Literature was used to commanding this kind of sacrifice. Over the years, we have paid this tribute in one way or another.

Death, sleep, and guilt remind us of nighttime. Night has always been connected with negation in human thought. But we say such things in a lighthearted fashion, without considering what terror there would be in this world if we were irrevocably separated from the night, if our calendars merely reflected an endless day. Until now, no one has bothered to carry out a research study on the role that the night plays in softening humanity. Without her intervention, without that restraint and interruption, human evil, anxiety, and anger would march forward at a catastrophic pace.

During its nascent stages, literature only knew about those dangers that threatened human life: erasure and oblivion. The rhapsodists sang, people heard them, and new rhapsodists emerged to sing new songs that died away with their singers or shortly thereafter. In this sense, literature confronted some of the same natural dangers as human life. Later on, literature was also confronted with dangers that came from another sphere, from society and the state. It was the theater, likely due to its ability to gather people in the center of cities, that first helped conjure the practice of censorship. Official censorship was thus born, over two thousand five hundred years ago, and it was so powerful that it created many problems for the literary giants of the time, the great tragedians.

Censorship is bound up with writing. Before the Akkadian-Sumerians invented writing, efforts to control oral poetry were inexact and not very persistent. At the most, a nonconformist rhapsodist would not be invited to sing at the gathering of a prince, and that was the end of the matter.

When writing appeared on the cultural horizon, it was like an unimaginable earthquake. Writing carried out a dual project. On the one side, it opened a new horizon for literature, while on the other hand, it suffocated, killed, and mummified it.

Prior to a new phase in its development, literature, in accordance with its stringent legal codes, always sought a heavy tribute from writers. They had to give up part of their spontaneity, to pass their thought through the wheels and banners of the heavy machinery of syntax. They could not criticize literature on any given day if they were in the mood to do so. Writing was thus a dual form of control. The control that derived from a kind of consciousness, prescient for its time, but also an official form of control. The history of writing is, above all, the history of the dangers confronting writers.

Some contemporary expressions that are connected to this, such as “this literary work can burn you” or “let’s hope this work doesn’t land on your head like a misfortune,” become surprisingly clear when we think about the clay tablets on which Sumerians recorded their thoughts. When the baked tablets were taken out of the oven carelessly, the writer could burn his hands. Or a literary work, let’s say a long narrative, could have been placed in the writer’s studio so as to cover an entire wall, and one day, either because it had been placed poorly, or because it had not been baked properly, or due to an earthquake, the tablet would fall on the writer and trap him underneath.

Like every new initiative, literature brought along many such dangers. These early possibilities were simple compared to the horrors that would follow, which have become well known.

The departure of Aeschylus from Athens was the first of many such departures. Aeschylus and Homer were humanity’s greatest writers until the fifth century BCE. At least one of these two great writers was obliged to abandon their home. (I say at least one, because we cannot exclude the possibility that Homer, as a traveling rhapsodist, could have been traveling so much that for him the notion of departure would have lost all meaning altogether.)

The departure or the banishment of writers was thus tied to literature, becoming part of its genetic code from early on. But the departure also changed over the centuries. Even as the weather in the world grew milder, its position vis-à-vis literature only grew harsher.

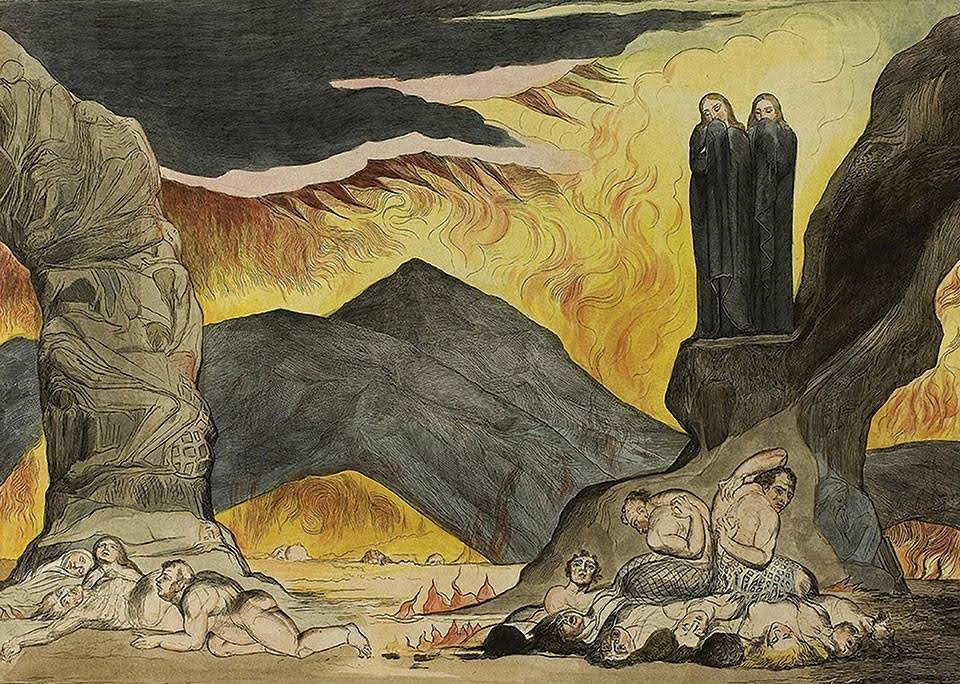

The departure of Ovid from Rome seems like the most painful, because unlike the departure of Aeschylus, where it was the anger of writers that assumed a deciding role, Ovid was sent away by the state. The repression of writers that continues to our time began with him.

In the case of Ovid, we have all the makings of future totalitarianism: condemnation with no known cause. The kind of suppression of the totalitarian state, where you yourself don’t even know why you’re being condemned. This unexplained terror, a blind strike, would remain one of the key devices of terror until the twentieth century, when communism, after having perfected its own devices, just like Kafka’s machine, would crumble along with it.

With their departure, great writers like Aeschylus and Dante Alighieri seemed to have been looking for a way to return to that zone, that climate, and that chaos in which literature was born. In other words, they sought to experience the status of a semideath, if not the depths of death itself. It was, perhaps, an internal order of art, of the same great ritual that suggested to Dante that before he started describing his journey into the inferno, he had to somehow separate himself from life.

At the same time, it must be said that up until Dante, writers, even in cases of misfortune, were generally treated as a seigneurial group. It was later dictatorships that understood that in order to attack writers better, they had to have their status lowered. So they made a habit of what had previously not been a habit: the imprisonment of writers, their placement in communal cells, their internment, their dishonoring, their movement by train from one camp to another, their insult, their reeducation through physical labor, and so on and so forth

In no other dictatorial regime has there been such a telepathic exchange between the tyrant and the people as under communism. Suffocating, irritating, terrifying, sleep-inducing, and intoxicating, the psychic echoes encompassed all this, and it was dominant.

The communist regime was one that more than any other regime took its battle against literature seriously. Communism and literature simply had no means of joint coexistence. The negative stance toward literature was not a later manifestation; it was inherent to communism. The shallow paragraphs by Marx about ancient literature or about Shakespeare were a mere alibi to cover up later crimes. There is no room for literature in the Marxist vision of the future world. Lenin’s seminal article, “Party Organization and Party Literature,” was as brutal in its effects as some of the fury of Genghis Khan. There is a red thread among communists that connects their treatment of literature, from Lenin’s articles, to Stalin’s executions, to Mao’s pathological hatred for writers, to the massacres of both writers and their readers by Cambodia’s Pol Pot.

Totalitarianism likewise surmised early on that it could not merely destroy literature through terror alone. It understood that a massacre alone would not do, that a suicide of sorts would also be needed to completely solve the problem of literature. Self-censorship, this long-standing, century-old disease, which literature confronted but overcame, communism attempted to turn into a real plague.

And it managed, in one way or another, to do so. Thousands of writers, most of them mediocre ones, surrounded literature’s temple from all sides. Their number grew daily, just as the number of true writers, who sought to keep alive the holy fire, decreased by the same measure.

Never has the literature of half the globe been confronted with such a danger. In totalitarian regimes, literature and the arts were tested cruelly, in a manner unknown in world history until then. We know about the punishment of writers even before: the censors, the prisons, and the camps were well known. But Stalinism went further. It did not satisfy itself with simply repressing well-known works, the ones sometimes called artistic cathedrals. It attempted to forever bury the possibility of their creation too. In other words, that system sought to destroy the raw materials whereby such cathedrals are built. It attempted to create a new race of writers, who would eagerly take upon themselves the destruction of literature. Stalinism achieved this in a way. Those of us who remained faithful to the temple were in the minority in that endless and hopeless desert known as socialist realism.

Writers were thus broken into two groups: those who betrayed the temple and those that stayed faithful to it. The divine question that could be posed to writers of the East—“What did you do, Adam?”—would have two possible answers. The first answer was: I degraded myself and literature according to communist law. And the second was: I continued to write normally, as though communism didn’t exist. When I hear questions like the ones frequently posed to writers of the former communist empire (namely, How did you continue to write normally, during a time and place when this seemed impossible?), my answer has been precisely this: we had faith in literature. It rewarded our faith and devotion with this blessing and protection.

To believe in literature means to believe in a higher reality. To believe in literature means that your country’s dark regime seems pale compared to the majestic literary funerary rites. To believe in this art means you always know that the government which dominates you, the police that surveil you, that the parliament, the bosses, the administration, tyranny itself, are a passing nightmare, dead matter, compared to the great order of which you have become initiated as a member.

So as not to drag on, let me repeat something that I have said elsewhere in connection with an episode of Dante’s Divine Comedy. While traveling through hell, Dante Alighieri is frightened for one moment by an approaching storm, and his master, Virgil, says: “Do not be afraid, it is a dead storm.”

Within these words we can find the explanation of what I mention above. To view the storms of the regime as dead storms is an unusual skill. And only writing can afford a writer this skill. It has never been easy for the writer to feel alive amidst all the surrounding death.

It has been said multiple times that to think normally in the mad communist world is an incredible stance. To speak normally is outright heroic.

Communism fell without fully realizing its perverse dream. We arrived at the end of this millennium without it. Our literature has lived in the world for three thousand years. Its first millennium was wealthy and bright. The second one was unfortunately less rich; it seemed as though humanity wanted to rest a bit during that time. And then the third millennium arrived, the one we are living in, which gave new life to literature. Let us hope that the new millennium, the fourth one, will not repeat the second, as though in a fatal symmetry.

During these difficult days, when the whole planet is experiencing the distress of a global pandemic, I want to express my regret that I cannot be present among you for a beautiful celebration that coincides with the fiftieth anniversary of this prestigious prize. Due to the impossibility of reaching you from my native Albania on the Adriatic, I wish to express my appreciation to the jury. I am honored that you have chosen me from among the most well-known authors in the world.

Thanks to the fabulous poet, Kapka Kassabova, who nominated me for this prize.

Thanks to Robert Con Davis-Undiano, executive director of World Literature Today, for his high consideration of my work. Thanks to the university, its students, and faculty.

Thanks to the talented translators of my work, David Bellos and John Hodgson.

And a special thanks and gratitude to the respected Neustadt family for their engagement and generosity in the promotion of world literature.

Tirana, August 2020

Translated from the Albanian by Ani Kokobobo

Main image: J.M.W. Turner, Ancient Italy—Ovid Banished from Rome, oil on canvas, 1838.

Frick Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

|

|

Ani Kokobobo is associate professor and chair of the Department of Slavic and Eurasian Languages and Literatures at the University of Kansas. Her writings have appeared with the Washington Post, LARB, and the Chronicle of Higher Education. |